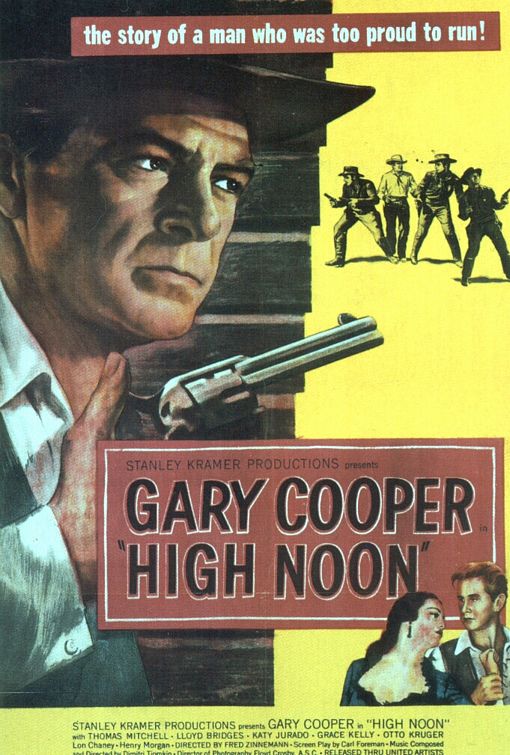

Sheriffen USA 1952

Sheriffen USA 1952

Bluray from Olive Films, USA (region A). Mastered from 4K restoration. Special features: “A Ticking Clock” (editor Mark Goldblatt on the editing), “A Stanley Kramer Production” (Michael Schlesinger on the producer), “Imitation of Life: High Noon and the Blacklist” (film historian Larry Ceplair and formerly blacklisted screenwriter Walter Bernstein), “Oscars and Ulcers: The Production History of High Noon” (a visual essay narrated by Anton Yelchin), “Uncitizened Kane” (essay by Sight & Sound editor Nick James).

The High Noon screenplay was written by the blacklisted Carl Foreman, and his decision to go into exile in Great Britain shortly before the premiere contributed to the film being regarded as a symbolic drama of the blacklist. Director Fred Zinnemann, who had lost his parents in the Holocaust, added that he saw it as a tale of moral consciousness and individual resistance in a time of threatened democracy. Perhaps because of this subtext in a climate of paranoia and right-wing populism, the public loved it and made the film into a resounding box-office success.

To those who hated it, it was “un-American” Two prominent detractors of the film were Howard Hawks and John Wayne, a champion of the House on Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC) witch-hunt on alleged communists. They made an anti-High Noon western called Rio Bravo in 1959, but although it also has become a something of a classic, it never reached the genre status that High Noon had and still has.

The reason is that High Noon’s story about sheriff Will Kane (Gary Cooper), who alone stands up to a band of crooks when everybody else has chickened out – of cowardice or opportunism or both – is archetypal. The protagonist is no tough guy, in fact he sweats heavily and at one point even cries in agony. But he remains the stubborn loner who refuses to sell out his integrity. He could be the Nietzschean superman refusing to embrace slave obedience, or the second coming of Christ who sacrifices himself for the sake of mankind. Or he is just an ordinary man with integrity and a moral codex.

Regardless, Kane went down as one of the most beloved American heroes of the screen, number five in America Film Institute’s vote on the popular 100 some years ago. And he would appear in the most surprising of contexts, like being the poster boy for the Polish trade union Solidarność (Solidarity) in the 1980s. Foreman based his screenplay on the short story “Tin Star” by John W. Cunningham, who in turn took it from Owen Wister’s classic novel The Virginian (1902) – whch in its turn probably stole a lot from numerous late-19th century pulp fictions and newspaper stories about sheriffs who cleaned up towns.

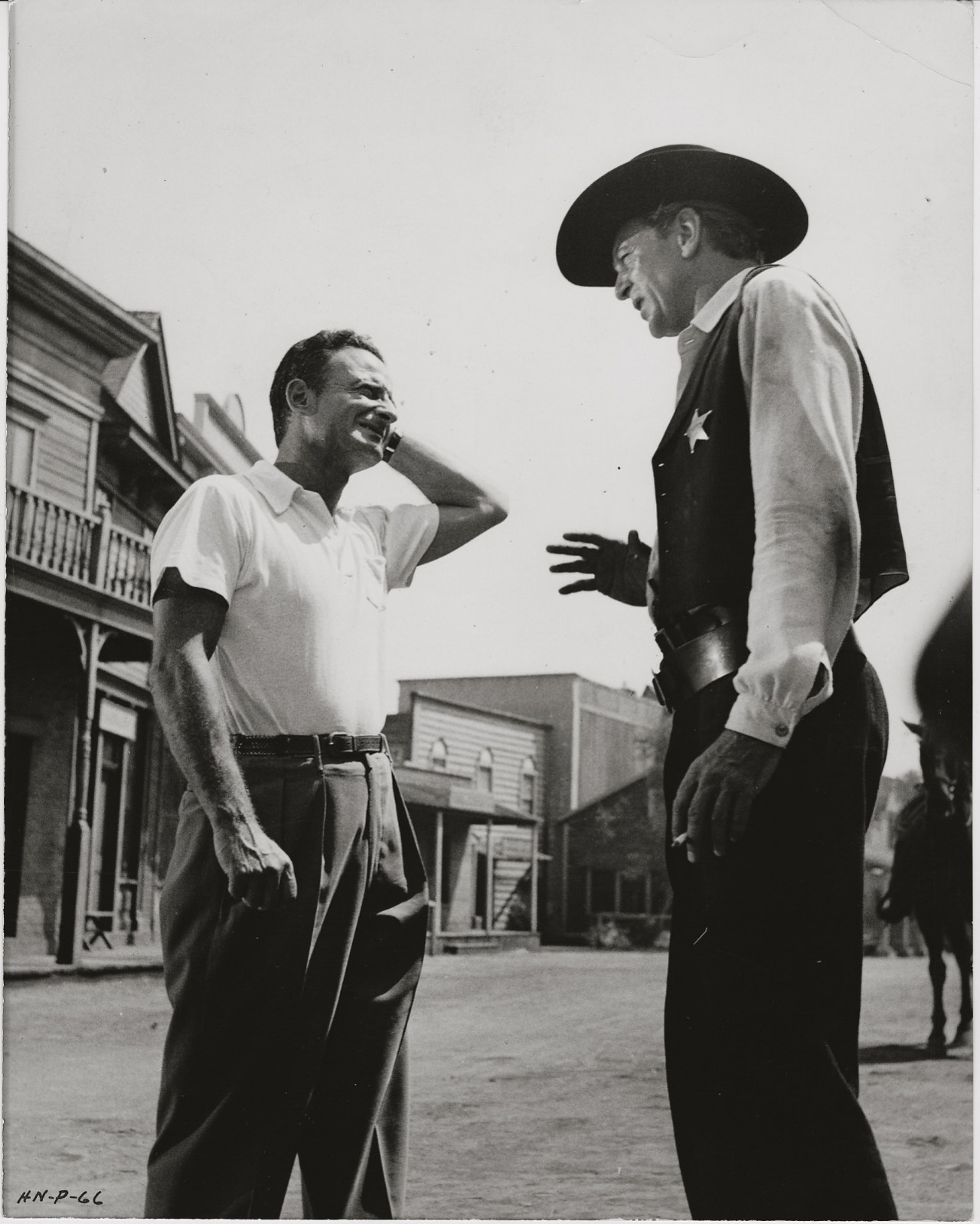

Zinnemann made the film in the summer of 1951 at several locations. The major ones were Iverson Movie Ranch, a preserved gold mining town close to Sonora, and Jamestown’s Sierra Railroad. It was shot without filters, which made most of the exterior shots look slightly overexposed, like a documentary. Today’s cineastes are perhaps also reminded of Ingmar Bergman’s nightmare scenes in Sawdust and Tinsel (Gycklarnas afton, 1953) and Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället, 1957).

Cooper, who at the time suffered from both back problems and a bleeding ulcer, gave Kane a haunted look. Under the merciless midday sun, he is all sweat and grit, pressing onwards down the mean streets of the western small town against all odds. For that he was awarded an Oscar.

Another Oscar was bestowed Tex Ritter’s hit song “Do Not Forsake Me, My Darling”, and the film gave newcomers Grace Kelly and Lee Van Cleef their first big break in Hollywood. But most of all, the film became important as the model for countless films by counting down the clock to the final showdown, gradually increasing the pressure on the sheriff and the thrills of the audience. In doing so, High Noon becomes a lesson in the art of telling a story economically. There is not an image or line too many, and the choice to let the narrative unfold in real time is genial.

Kane (and we) checks the clock, again and again. Gradually, the realization sinks in that no one will help him when the main villain Frank Miller (Ian McDonald) arrives on the high noon train to lead his gang in bloody vengeance. The final showdown is almost silent, with no music and very little dialogue, just masterful editing. After the final killing, the townsfolk all come out to congratulate the last man standing. In disgust, Kane throws his badge in the dust and leaves town without a word. That scene has become one of the most iconic in the history of Western films, imitated by many, for example by Don Siegel and Clint Eastwood in the closing shot of Dirty Harry (1971).

To genre historians such as Will Wright and Edward Buscombe, the image signaled the transition from an idealistic era of films about true-blue heroes fighting for nation, decency and democracy to darker stories about greed, revenge and genocide. A new kind of western appeared, one in which the differences between good and bad, hero and villain, were blurred. This transition had already started in the late 1940s with more realistic and psychologically more complicated films like the Raoul Walsh’s Freudian Pursued (1947) and continued with Anthony Mann’s so-called western noirs, beginning in 1950 with Winchester’73.

However, the popularity of High Noon made it a turning point in the history of the western, a sobering wake-up call from Hollywood’s fairy tale dreams of a Neverland called the West.

© Michael Tapper 2016. Web exclusive: michaeltapper.se 2016-10-21.