USA/China 2015. Directed by Colin Trevorrow Screenplay Rick Jaffa, Amanda Silver, Derek Connolly, Colin Trevorrow Story Rick Jaffa, Amanda Silver based on characters by Michael Crichton Cinematography John Schwartzman Editor Kevin Stitt Sound Designer Al Nelson, Gary Rydstrom Production Designer Ed Verraux Music Michael Giacchino. With Chris Pratt Owen Bryce Dallas Howard Claire Vincent D’Onofrio Hoskins Ty Simpkins Gray Nick Robinson Zach Jake Johnson Lowery Irrfan Khan Masrani Omar Sy Barry B.D. Wong Dr. Henry Wu Judy Greer Karen. Producers Patrick Crowley, Frank Marshall Production Companies Amblin’ Entertainment in association with China Film Co. and Legendary Pictures for Universal. Running Time 2.04.

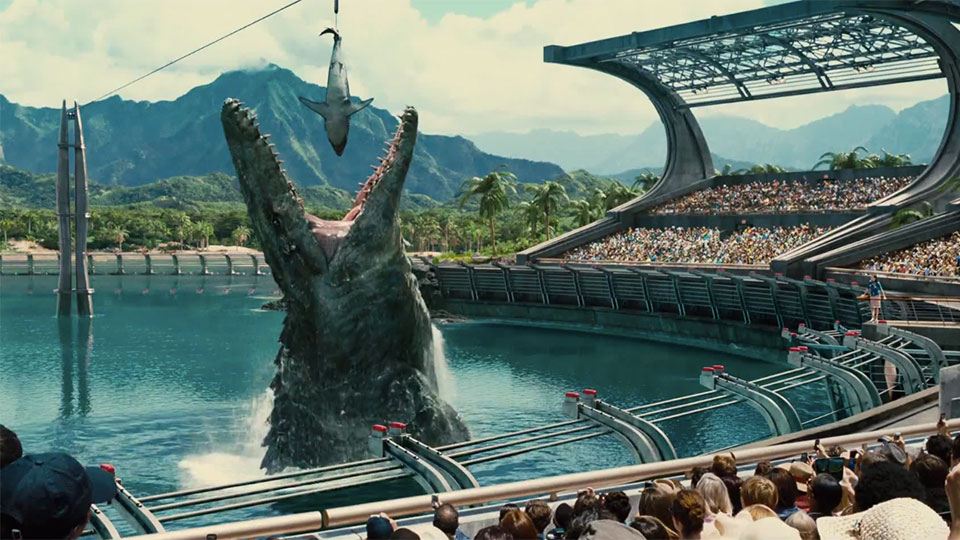

Isla Nublar, the present. Brothers Zach and Gray arrive at dinosaur park Jurassic World on the invitation of their maternal aunt Claire, the park’s managing director. Busy handling the genetically modified dinosaur Indominus Rex, she assigns one of her assistants to escort the boys around the park, but the boys soon breaks away from their guardian to explore the attractions on their own. In the safari part of the park they drive through the broken gate of a restricted area and comes under attack from the GM dino, who has recently escaped from its compound. Jurassic World owner Masrani lets the InGen security staff under the shady Hoskins take over the park and start to evacuate the +20,000 visitors on boats. After watching a group of soldiers with stun guns being killed by the Indominus Rex, he takes another military team on a helicopter with machine guns to kill it. Chasing the dinosaur the helicopter crashes into another compound, releasing various pterosaurs, who attack the visitor’s centre. Claire gets help from ex-marine employee Owen, who has been trying to communicate and even train a group of Velociraptors in the park. Hoskins plans to use Owen’s results for military purposes, making the raptors into a new asset for the army. He therefore orders Owen to put his work to the test by leading the raptors in an attack on the Indominus Rex. After much hesitation, Owen agrees to do so with his colleague Barry. However, confronting the new dinosaur, they discover it is part raptor and thus able to communicate with its smaller cousins. The raptors therefore accept it as their new alpha female and turn on the humans. Meanwhile, Zach and Gray has managed to get back to the visitor’s centre. They watch as Owen manage to turn the raptors back against the Indominus Rex. Claire releases the Tyrannosaurus Rex, and it also goes into battle with the dino baddie. Just when the Indominus Rex seems to be victorious, a giant Mosasaurus Hoffmannii jumps up from the park’s pool and kills it. The next morning, Zachs and Grays parents arrive to take care of their sons. Owen and Claire strike up a relationship.

They never learn from past mistakes, do they? Neither in the slasher movies, nor in the Jurassic Park films. You could, of course, argue that if they did, we would not have any sequels with higher body counts, more idiots with a sinister agenda – here, the plans to use Velociraptors for military purposes – and greed/megalomania/mad science running rampant. In fact, one could very well argue that this is the perfect reflection of the state of the world at the moment. Hence, we get the films we deserve.

They never learn from past mistakes, do they? Neither in the slasher movies, nor in the Jurassic Park films. You could, of course, argue that if they did, we would not have any sequels with higher body counts, more idiots with a sinister agenda – here, the plans to use Velociraptors for military purposes – and greed/megalomania/mad science running rampant. In fact, one could very well argue that this is the perfect reflection of the state of the world at the moment. Hence, we get the films we deserve.

It is no accident that the only character remaining from the first film is dino designer Dr. Wu, a Frankensteinian nihilist and opportunist who neither can nor will grasp the moral and ecological implications of his work. Instead, the voice of Gaia philosophy is ex-elite soldier Owen, played by Chris Pratt with an obvious reference to his colleague Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) in AVATAR (2009), a franchise to be continued in 2017 with Jurassic World’s Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver writing the script. Prepare for yet another example of a capitalist folly, packaged in yet another a capitalist folly.

Director Colin Trevorrow (Safety Not Guaranteed, 2012) is merely an instrument for producer Steven Spielberg and does not bring anything of his own to the series. In fact, Jurassic World is essentially both a rehash of and a sequel to Jurassic Park (1993), ignoring the previous sequels Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) and JURASSIC PARK III (2001). The plotting, the subtext and the main characters are largely the same.

Two kids get lost in the park and comes under attack from rogue dinosaurs. An outsider tries in vain to warn about the consequences of tampering with life. The park owner and managers watch in horror as their pet project goes to hell. Minor characters – mostly coded as stupid, cowards and/or aesthetically repulsive (for example the two fat men, played by Wayne Knight in JR and Eric Edelstein in JW) – are killed and eaten. Finally, a major battle between the scariest dinosaurs ends the threat to the protagonists, who in classical Spielbergian fashion embrace or restore faith in heteronormative relations and so-called family values as they leave the island of biological abnormalities. The End.

However, one essential ingredient in the success formula of Jurassic Park is missing in Jurassic World: the sense of wonder. I can still remember the “ooohs” and the “aaahs” in the cinema when we got a first glimpse of the CGI and animatronic dinosaurs in 1993. The new film is dedicated to the late animatronic wiz Stan Winston, who made some of the most memorable creatures back then – the Tyrannosaurus Rex, for instance. Now everything fantastic is digital, and the lack of the monsters’ physical presence is tangible. Together with the bland characters and actors in the predictable formula plot makes for a listless movie experience.

The filmmakers seem to be acutely aware of this and use Claire as their ’ironic’ mouthpiece for how the park – read: the film – must provide more shocks, teeth and terror in order to lure the public back into the seats. Already before the premiere there was a number of articles out on the net about the CGI artificiality of the film, but the film’s acknowledgement of this criticism does not make for a more exciting ride through the theme park of attractions. On the contrary, it transfers the cynicism behind the park portrayed in the film to the film itself, and we are supposed to laugh at our stupid consumerism while consuming some more.

Underlining the meta-bland blandness is Michael Giacchino’s score. It takes cues from John Williams’ original composition while not adding anything more than standard action music suitable for shopping mall playgrounds. Topping this auto-deconstruction strategy is the acknowledgement that the dinosaurs we see are creations made to fit our expectations rather than palaeontology updated for the last 20 years. No feathers, no striking colours, no features that might challenge our concept of what Velociraptors or T-Rexes might look like are introduced. Instead, we get outdated portraits in an outdated movie.

© Michael Tapper, 2015. Web only: michaeltapper.se 2015-06-11.