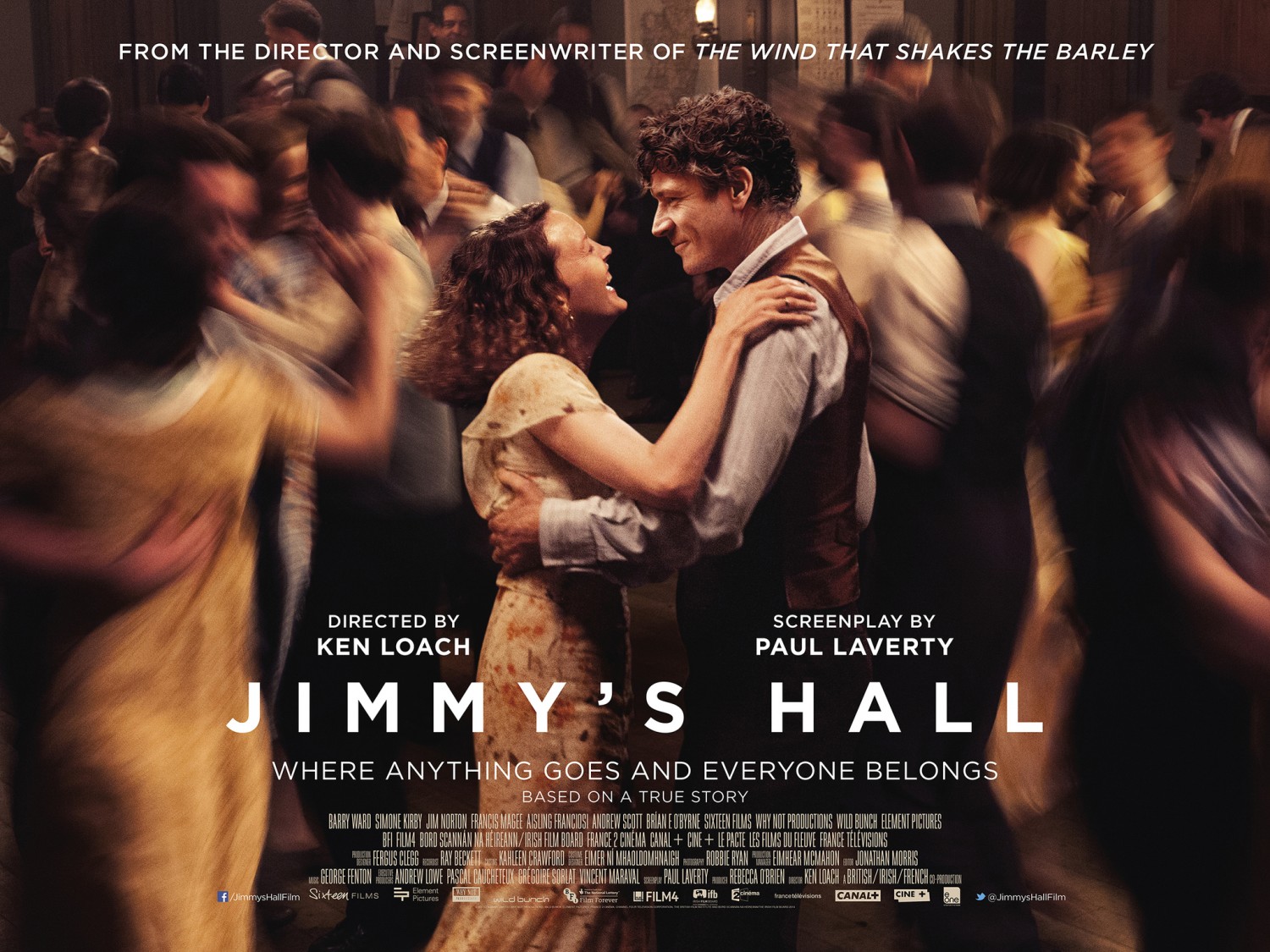

United Kingdom/Ireland/France 2014. Directed by Ken Loach Screenplay Paul Laverty Based on Jimmy’s Hall (play) Author Donal O’Kelly Cinematography Robbie Ryan Editor Mike Andrews Sound Editor Kevin Brazier Production Designer Fergus Clegg Music George Fenton. With Barry Ward James Gralton Francis Magee Mossie Simone Kirby Oonagh Aileen Henry Alice, James’ mother Jim Norton Father Sheridan Brian F. O’Byrne Commander Dennis O’Keefe Karl Geary Sean Aisling Franciosi Marie. Producer Rebecca O’Brien Production Companies Sixteen Films, Element Pictures, Why Not Productions & Wild Bunch with the support of Film4, Irish Film Board & British Film Institute. Running Time 1.46.

Effernagh, County Leitrim, Ireland, 1932. After a decade in New York, James ‘Jimmy’ Gralton returns to his widowed mother. At the request of his friends and neighbours – many of them unemployed because of the Depression – he reopens the old Pearse-Connolly Hall, a place he ran before emigrating. It soon becomes a community centre for dancing, education and political activism. However, history repeats itself when the local priest, father Sheridan, and the right-wing militia under Dennis O’Keefe again targets the hall, calling it an instrument for recruiting people to the communist cause. After some skirmishes the hall is burnt down and Jimmy is deported back to the USA on the grounds that he has an American passport. A text announces that never returned to Ireland and died in New York in 1945.

In what is rumoured to be Ken Loach’s final feature film, the veteran director has chosen to make a companion piece to his 2006 Cannes Palm d’Or winner The Wind That Shakes the Barley. We are now in the aftermath of the Irish war for independence 1916–21, followed by the 1922–23 civil war between the right-wing militia in favour of a treaty with the British (leaving Northern Ireland under London rule) and those against it. Backed by the British, the former side won, leaving the country divided and embittered for generations. But as the Fiánna Fail – the post-1923 anti-treaty party – took government in 1932, a new spirit of unity was declared and the real-life model for this film decided to come home from New York.

James Gralton (1886–1945) was one of the well-known heroes from the war of independence and also an outspoken communist. Most of his education came from his mother Alice, who acted as an agent for a circulating library in Gowel. In his early teens he had gone to Dublin, where he worked as a bartender before joining the British Army. Refusing to serve in India, he deserted and worked for some time in the Liverpool docks and some Welsh coal mines.

He immigrated to America in 1907 and joined the US Navy, which automatically provided him with a US citizenship. There he also joined the communist party. After the 1916 Irish uprising he became an active fundraiser for the independence, and in 1921 he returned to his home to train volunteers for the war while propagating for social issues such as land redistribution. On his family’s land he also opened the Pearse-Connelly Hall as a community centre, providing education for young school-leavers but also housing social events such as dance nights and political and union meetings. From time to time, the hall was used for Sinn Féin courts and to settle land disputes.

As is shown in the film, the church and the right-wing militia threatened Gralton and accused him of taking forcible possession of disputed land. He therefore returned to America in 1922 only to return a decade later because of the death of his brother and the poor health of his parents. Not only did he reopen the hall, he also joined both Fiánna Fail and the IRA and – again – became a target for the right-wing militia and the church. Unfortunately, Gralton’s political activism is largely invisible in the film, which is odd considering his reputation as outspoken and even blunt in his political activism. Also, Loach has never been known to sway from addressing ideological issues straight. Until now, apparently.

On December 24th 1932 the hall burnt down, and in August 1933 Gralton was deported. The government files on him were changed, stripping him of all his credentials from the war for independence. The IRA support for his cause was divided since the organisation did not want to become associated with communism. Some joined the witch-hunt, others – mostly labour and trade-union groups – spoke out against the deportation order. The protests is also something the film, oddly enough, shies away from. Returning to New York, Gralton continued as a communist activist and worked during World War II at a radio station. Shortly before his death from stomach cancer in December 1945 he married a girl from his county, Bessie Cronogue.

In the film Bessie is for some unknown reason replaced by the fictional Oonagh, supposedly some lost love from Gralton’s youth. Their big romance, interrupted by his emigration and her marriage to a local boy, is contrived and badly executed. Sadly, Loach also makes the mistake of making it more prominent during the course of the film, sidestepping the story of social activism, not to mention the many other and more interesting aspects of Jimmy Gralton’s life. For instance, making an extensive background story about him and his hall as it were in 1922–23, perhaps also his uneasy relationship with both Fiánna Fail and the IRA after his return in 1932.

Not many viewers, especially not outside of Ireland, knows much, if anything, about the Irish civil war, Gralton or the disgrace of his treatment, and the film makes nobody any wiser. Even a more traditional biography film had been a better narrative strategy than the dull and empty sentimentality Loach fumbles with here. Sadly, that mode also intrudes on the final moment of solidarity, when Gralton’s friends turns up at his deportation, leaving the viewer with a feeling of sad but inevitable defeat where defiant resistance ought to be – and should be in a Ken Loach film.

If the film as an overall experience is a frustrating, sometimes even downright embarrassing, it is nonetheless brilliant in singular scenes. The confrontations between Gralton (Barry Ward) and Father Sheridan (Jim Norton) are the dramatically most satisfying since their animosity escalates into a moral showdown in the church’s confessional. Here the film picks up on a line dropped in a previous scene, in which Sheridan’s young apprentice for priesthood claims that Christ would probably be crucified again if he reappeared in the parish. It also becomes a poignant corrective to Sheridan’s sermon about the evil of materialism.

For Loach, the pleasures of love, work and solidarity in the flesh always takes precedence over the promise of a pie in the sky when we die. Considering that Jimmy’s Hall could be the last film in Ken Loach’s and his trusty screenwriter Paul Laverty’s illustrious careers the final thoughts of this film should perhaps be on the moments they loved to highlight as the best in a human life: the spirit of community. These are best expressed in his scenes of singing, dancing, laughing and learning. Not as individual achievements but as expressions of the fellowship of the working class, perhaps also of civilization at its very roots.

For me, the most heartfelt moment of that sentiment in the film is the scene in which Jimmy presents his gramophone to his friends, puts on a jazz record and teaches them a new dance from halls across the ocean. He fondly recalls his visit to a dance hall in Harlem, where people of all creed and colour mixed and danced together as equals. Like his own hall, it is a beautiful island of dreams waiting to be fulfilled by an ugly and unjust world.

© Michael Tapper, 2015. Web exclusive 2015-08-07.