Deux jours, une nuit

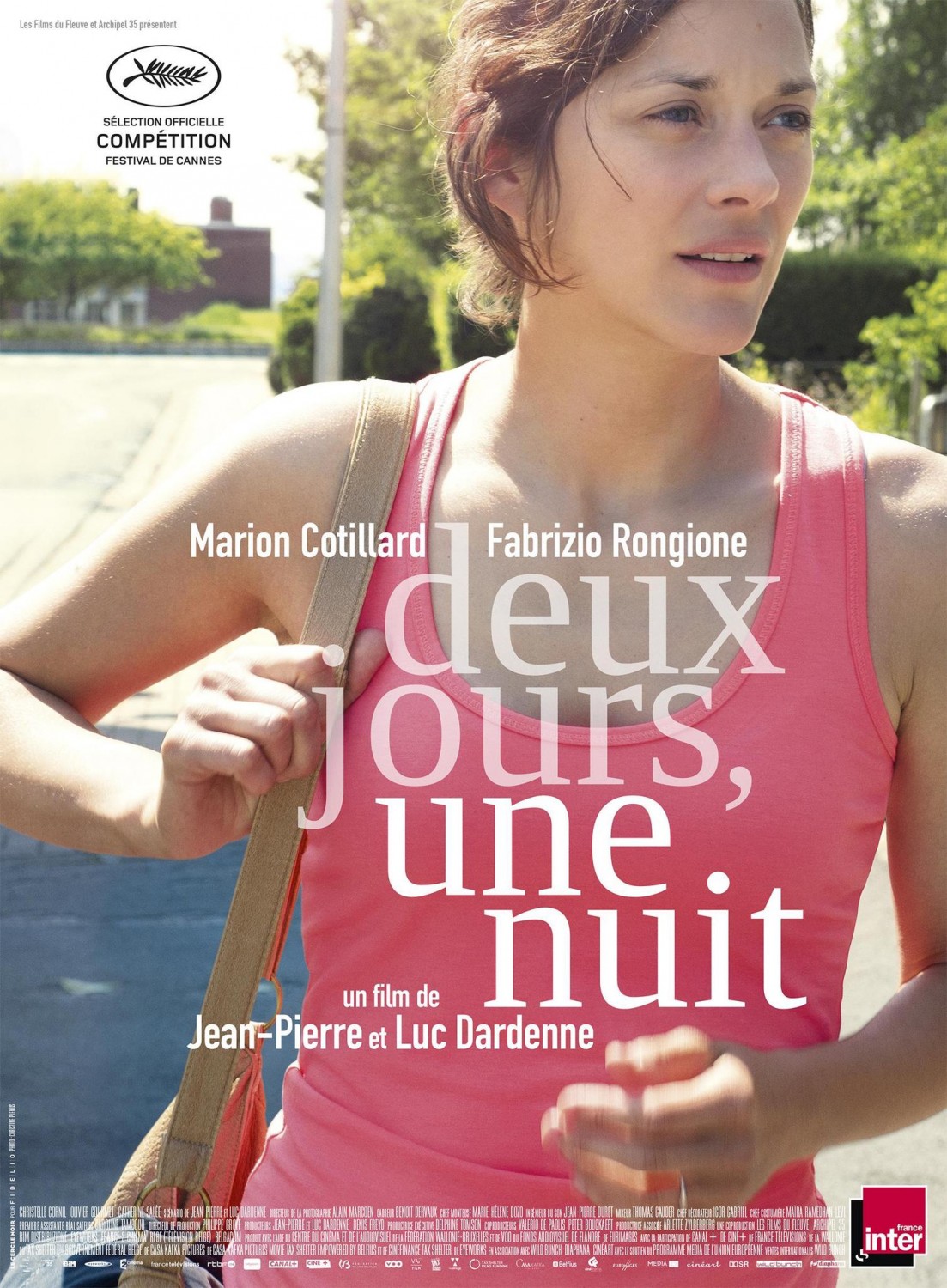

Belgium/France/Italy/The Netherlands 2014. Director, screenplay Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne Director of Photography Alain Marcoen Editor Marie-Hélène Douzo Production design Igor Gabriel With Marion Cotillard Sandra Bya Fabrizio Rongione Manu Pili Groyne Estelle Simon Gaudry Maxime Catherine Salée Juliette Baptiste Sornin Dumont Philippe Jeusette Yvon Yohan Zimmer Jean-Marc Serge Koto Alphonse Producers Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne, Denis Freyd Production companies Les Films du Fleuve, Archipel 35, Bim, Eyeworks in coproduction with France 2 Cinéma, RTBF (Télévision Belge), Belgacom supported by Canal+, Ciné+, France Télévision, Centre du Cinéma et de l’Audiovisuel de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, VOO, Flanderns Audiovisuella Fond, Eurimages, Wallonie, Casa Kafka Pictures, Belfius, Cinéfinance, Eyeworks, Wild Bunch, Diaphana, Cinéart, EU:s MEDIAProgram with the tax shelter of the Federal Government of Belgium. Runtime 1.35 (95 minutes) BD/DVD Artificial Eye (French dialogue, English subtitles) Extras Interviews with the Dardenne brothers and Marion Cotillard.

Seraing, Wallonia. Friday. Sandra Bay is about to go back to work after a severe depression. However, she learns that her boss, Dumont, has called for a vote among the other 16 employees at the small firm Solwal, a company manufacturing solar panels. Voting either for a bonus of 10,000 Euro or for Sandra to come back to work, the majority choose the bonus. Juliette is infuriated by the fact that the foreman, Jean-Marc, lobbied against Sandra with slander, making Dumont promise to have a new and secret ballot on Monday. Over the weekend Sandra goes off with her husband Manu to persuade the other workers to vote for the continuation of her employment, thus losing their bonus. Some promise to support her, others reject her outright, claiming to be in need of the money. In one case her visit starts a fight between two male co-workers, and in another case a female co-worker leaves her husband after a quarrel about the bonus. Sandra feels so miserable about her situation that she tries to commit suicide, but Manu drives her to the hospital to get her stomach pumped. On Monday morning the vote is split, eight against eight. Sandra is called to the office, and Dumont offer Sandra to come back once he has cancelled the contract with another worker, Alphonse, who is of African origin and voted in her support. Sandra declines his offer and leave the factory with a smile on her lips.

The film art of the Dardenne brothers have never impressed me much. In form their films are simple, even banal, and like many others in their generation (Werner Herzog, Roy Andersson et. al.) they confuse social criticism with a dark and deterministic view on life as a misanthropic mystery. In a time when despair and hopelessness has nourished the growing Fascism in Europe, attracting voters with simple and brutal solutions, this celebration of – at best – comfortably numbing.

The film art of the Dardenne brothers have never impressed me much. In form their films are simple, even banal, and like many others in their generation (Werner Herzog, Roy Andersson et. al.) they confuse social criticism with a dark and deterministic view on life as a misanthropic mystery. In a time when despair and hopelessness has nourished the growing Fascism in Europe, attracting voters with simple and brutal solutions, this celebration of – at best – comfortably numbing.

A glimpse of change is visible in The Kid with a Bike (Le Gamin au vélo, 2011), a film the Brothers called a fairy-tale, in which a female hairdresser turns out to be the good fairy to a troubled young boy. Here a glimmer of hope is finally visible in the otherwise overwhelmingly grey life in Wallonia, although it is clearly a fantasy. However, in Two Days, One Night there is, at last, a deeper social and political calling for a change that will improve the conditions for the working-class that they claim to speak for.

I am therefore baffled to read the review in the September issue of Sight & Sound, in which Tony Rayns banters about the film as a feel-good flick with a liberal-democratic leaning. He claims the film mixes uplifting support and angry backlashes into a sentimental and likeable melodrama with some thriller spice in the deadline that is set by the new ballot on Monday morning. The political sting is in his view blunted by the fact that Sandra’s workplace does not have a trade union, which takes away a more complicated view of labour politics and reduces the vote to a moral and personal issue.

I am sure there are movies like the ones Rayns describes, but Two Days, One Night is not one of them. Perhaps it is a celebrity issue, i.e. that he regards the film as mapped out for Marion Cotillard’s triumphant victory as a working-class heroine. No doubt you can find loads of screenplays tailored for the benefit of the star’s need for ego masturbation, although there is no such trace of it here.

Sure, there are flaws, such as the episodic and rather fragmented narrative and the all-too angelic self-sacrifice of the husband. Though we shall not underestimate man’s ability to act in empathy and altruism, Manu becomes close to a rerun of the fairy-tale hairdresser in The Kid with a Bike. The children are also out of the story in a quick and convenient haste, as if they were of no significance. Perhaps the Dardenne brothers have no children and cannot relate to a family situation, but it is a significant blind spot to me.

Sure, there are flaws, such as the episodic and rather fragmented narrative and the all-too angelic self-sacrifice of the husband. Though we shall not underestimate man’s ability to act in empathy and altruism, Manu becomes close to a rerun of the fairy-tale hairdresser in The Kid with a Bike. The children are also out of the story in a quick and convenient haste, as if they were of no significance. Perhaps the Dardenne brothers have no children and cannot relate to a family situation, but it is a significant blind spot to me.

Cotillard, on the other hand, is the film’s great asset. There are no signs whatsoever of glamour, gloss, artificiality or mannerisms in her portrait of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Sandra’s many tears and display of self-contempt might even alienate many in the audience. At first glance, some will probably dismiss her a classical example of hysteria, and in the newspeak of neoliberalism she would be defined as one of those unfit to compete in today’s labour market and therefore destined to walk in the margins of society.

Sandra is the perfect example of the precariat, hitting rock bottom in the social Darwinist hierarchy. She is so utterly flattened by the brutal conditions that she readily accepts all the degradation and injustice she is served. Thanks only to the support of the husband and her work-mates, she is able to rise from the apathy of depression.

Sandra is the perfect example of the precariat, hitting rock bottom in the social Darwinist hierarchy. She is so utterly flattened by the brutal conditions that she readily accepts all the degradation and injustice she is served. Thanks only to the support of the husband and her work-mates, she is able to rise from the apathy of depression.

Her desperate weekend tour to her colleagues is a mixed experience of both a crucifixion and rehabilitation. Some co-workers try to dodge their moral responsibility repeating that the ballot was no idea of theirs and that they did not vote against here but merely for a bonus – and that’s okay, isn’t it? The argument is a small-scale version of the individualist propaganda that by warped logic has made a dramatically increasing inequality possible in the Western world. We are made to think only of our own short-sighted need without any regard for the consequences to others and to future generations. A psychopath’s logic.

The ballot itself is a good example of an impotent democracy, one in which we only can vote according to certain premises. It is also a good strategy for manufacturing consent. No one questions why they should choose between Sandra’s job or for a bonus. Why not vote for an equal pay that makes it possible for everyone to stay and get a bonus?

For those of us who reflect on the crisis mind-set we have been living with during the last decades the pattern is clear: The profits of the corporations, the wages of the top-executives, the bonuses of the shareholders and the riches of the upper-class have been increasing dramatically. At the top, no one has a crisis. They are not the problem. They are not to blame. It is we, the other 98 per cent, who have to be responsible, and the crisis mind-set is the one that makes the have-nots tighten their belts so the haves can get more. In order for us to do this voluntarily we have to filter the world through the same cynical looking-glasses as the ruling elite, seeing the world as one of selfishness, envy and greed.

Even if Sandra does not win the second ballot, the double twist of her losing the job only to be offered it back by taking someone else’s place is an eye-opener. Strengthened by the fact that half of the staff had the courage to stand up for her give her a new sense of integrity and self-confidence. Hence, solidarity is not just a word. The film gives it a special meaning for the audience today. That alone makes Two Days, One Night one the best films of the year.

© Michael Tapper, 2014. Web exclusive 2014-12-13.