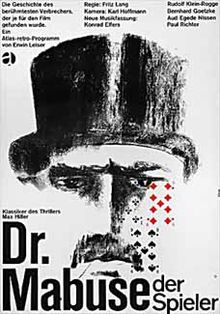

Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (Dr Mabuse, der Spieler, 1922)

Part I: The Great Gambler – A Picture of the Time (Der Grosse Spieler – ein Bild der Zeit)

Part 2: Inferno: A Play About People of Our Times (Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit)

Germany<

Director Fritz Lang Screenplay Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang Based on the novel by Norbert Jacques Producer Erich Pommer Director of Photography Carl Hoffmann Art Director Carl Stahl-Urach, Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht Costumes Vally Rienecke.

With Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Dr Mabuse), Aud Egede Nissen (Cara Carozza), Bernhard Goetzke (State Prosecutor von Wenk), Alfred Abel (Count Told), Gertrude Welcker (Countess Told), Paul Richter (Edgar Hull), Robert Forster-Larrinaga (Dr Mabuses manservant).

Runtime 155 minutes (part I, 22 fps), 115 minutes (part II, 22 fps).

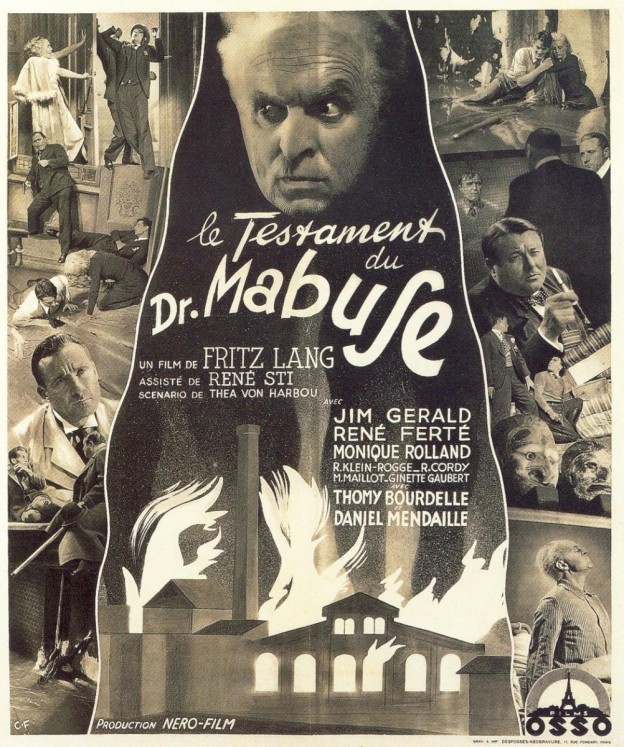

The Testament of Dr Mabuse (Das Testament des Dr Mabuse, 1933)

Germany

Director Fritz Lang Screenplay Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang Based on characters created by Norbert Jacques Producer Seymour Nebenzal, Fritz Lang Director of Photography Karl Vash, Fritz Arno Wagner Art Director Emil Hasler, Karl Vollbrecht Costumes Hans Koth ke.

ke.

With Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Dr Mabuse), Otto Wehrnicke (Detective Inspector Lohmann), Oskar Beregi (Dr Baum), Gustav Diessl (Thomas Kent), Wera Liessem (Lilli), Theodor Loos (Baum’s assistent), Klaus Pohl (Müller).

Runtime 116 minutes (orig. 122 minutes).

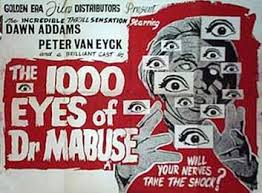

The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse (Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse, 1960)

West Germany

Director Fritz Lang Screenplay Fritz Lang, Heinz Oskar Wuttig, Jan Fethke Based on characters created by Norbert Jacques Producer Fritz Lang, Alfred Bittins, Artur Brauner Director of Photography Karl Löb Art Director Erich Kettelhut, Johannes Ott Costumes Ina Stein.

With Dawn Addams (Marion Menil), Peter Van Eyck (Travers), Wolfgang Preiss (Jordan), Gert Fröbe (Detective Inspector Kras), Wolfgang Preiss aka Lupo Prezzo (Cornelius), Werner Peters (Hieronymos P Mistelzweig), Andrew Checchi (Hotel Detective Berg).

Runtime 109 minutes.

The Complete Fritz Lang Mabuse Boxset

DVD (four discs)

United Kingdom 2010

Produced and Distributed by Eureka Entertainment (region 2)

Aspect Ratio 1.33:1 (b/w)

Sound Mix Mono 1.0

Extras Original German titles for Dr Mabuse, de Spieler. New English subtitles for all three films. Commentaries to all three films by David Kalat. Featurettes: 1. Mabuse’s Music 2. Norbert Jacques: The Literary Inventor of Dr Mabuse 3. Mabuse’s Motives. A 2002 interview with Wolfgang Preiss. Alternate ending to The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse (French print). English dubbing track for The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse. Three booklets (with production stills and interview excepts): “Sensation of Culture” (a 1924 lecture by Fritz Lang), essay by Michel Chion on the use of Sound in The Testament of Dr Mabuse, essay by David Cairns on The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse.

three films. Commentaries to all three films by David Kalat. Featurettes: 1. Mabuse’s Music 2. Norbert Jacques: The Literary Inventor of Dr Mabuse 3. Mabuse’s Motives. A 2002 interview with Wolfgang Preiss. Alternate ending to The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse (French print). English dubbing track for The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse. Three booklets (with production stills and interview excepts): “Sensation of Culture” (a 1924 lecture by Fritz Lang), essay by Michel Chion on the use of Sound in The Testament of Dr Mabuse, essay by David Cairns on The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse.

With DVD transfers from prints restored by F W Murnau Stiftung and lively commentaries on everything Mabuse by David Kalat, author of The Strange Case of Dr Mabuse: A Study of Twelve Films and Five Novels (2005), the Eureka collection of Fritz Lang’s three Mabuse-films is a must-buy for anybody with the slightest interest in film history. Not only are they cleaned up visually, the two first films are presented in almost complete versions. In fact, no books on Lang (by Eisner, Armour, Gunning, McGilligan and Grant) have a running time on the two parts of Dr Mabuse, the Gambler that match those in this edition. McGilligan, for instance, clocks part one in 120 minutes and part two in 93 minutes. That is 35 and 22 minutes respectively shorter than here. In part, this might be because they for the first time are presented in the correct speed of 22 frames per second and not in 24 as have been usual in the decades before, but it still leaves room for much new stuff.

As crime narratives, they stand up remarkably well today. Even at four and a half hours, Dr Mabuse, the Gambler is a fast-paced, multi-layered, genre-transgressing epic (gangster, spy, urban comedy, social comment, occult horror, conspiracy thriller etc.) that is far more complex, modern and daring in its social critique than most of the post modern rehashes of old tricks today, ninety years later. In fact, this last year there has been consistent rumours about a remake, which will make for an interesting comparison whatever the result. My only reservation about this edition is Aljoscha Zimmermann’s music. Although it is sensitive to the changes in mood and tempo in the narrative, a more experimental score in the mode of one of the tracks featured in the BFI Edition of The Man with the Movie Camera seems more appropriate. Also, contemporary jazz music in some of the scenes at the night clubs and cabarets should be the preferred choice, as the inserts of bands playing there indicates.

Often quoting from his Mabuse book, Kalat challenges some of the myths often voiced about the Testament sequel. Already in the research Patrick McGilligan made for his Lang biography The Nature of the Beast (1997) there is much proof to counter many of the claims Lang himself made about the film, the German ban and his exile: There is not any evidence (document, diary note) of a meeting with Goebbels at the end of March, in which he – despite being part Jewish – supposedly was offered to be an Ehrenarier (honorary Aryan) and the “Führer of Nazi films” at UFA turned Nazi propaganda factory. Nor did Lang leave Germany that very night, but much later, in June, then returning several times during the autumn of 1933 to finalize his divorce from Thea von Harbou, drawing his life saving from the bank and getting much of his belongings out of the country.

Kalat goes on to question Testament as metaphor for the Nazi movement, i.e. the artistic intention of depicting Mabuse’s plans for a Herrschafft des Verbrechens (Rule of Crime) as mimicking Hitler’s plans, even down to quoting Nazi slogans in the dialogue of the criminals. He points to the fact that the cast and crew were divided into both Nazi party members and opponents, that Goebbels showed it unaltered for the crowd at his birthday party and that Goebbels again, with just small changes and additions, made the film into a an acceptable story about the gangster capitalism during the early Weimar republic. Could a decisively anti-Nazi film so easily be redressed to suit another ideological agenda? Instead, he says, it was the dubbed 1943 American version made from the French print that created the legend by altering both the story and the dialogue to enhance the interpretation of the film in accordance to the Lang legend. Given other facts of Lang’s anti-Nazi sentiments, I am not sure the film is entirely free from intended parallels to Hitler’s rise to power, but Kalat certainly has a case for casting a shadow of a doubt on this legend.

The Thousand Eyes was, for me, the most startling revelation in this box set. Frequently dismissed as of minor interest, a sad ending for a director going blind and losing his creative touch, I found it most challenging. With its complex plot and subplots of self-consc ious role-play, deceiving appearances, voyeurism, surveillance techniques and TV as the new instrument for totalitarian manipulation, it is a poignant prophesy about the brave new Mabuse world in the years to come. Countless docusoaps (Big Brother et al) or fake-docu-paranoia-series such as 24 (2001-10) and Spooks (2002-), films like Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes, Peter Weir’s The Truman Show (both 1998) and Marc Evans My Little Eye (2002) – they all seem to be derivations from this new level of Mabuseism. Not to mention the exponential growth of camera surveillance in public places and Internet monitoring in the name of both dictatorship and democracy in the real world.

ious role-play, deceiving appearances, voyeurism, surveillance techniques and TV as the new instrument for totalitarian manipulation, it is a poignant prophesy about the brave new Mabuse world in the years to come. Countless docusoaps (Big Brother et al) or fake-docu-paranoia-series such as 24 (2001-10) and Spooks (2002-), films like Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes, Peter Weir’s The Truman Show (both 1998) and Marc Evans My Little Eye (2002) – they all seem to be derivations from this new level of Mabuseism. Not to mention the exponential growth of camera surveillance in public places and Internet monitoring in the name of both dictatorship and democracy in the real world.

Especially interesting is the stressing of the continuity between Nazi Germany and the post war world. In setting the main action within a hotel built by the SS for monitoring and controlling the inhabitants and now in control of Mabuse’s still loyal followers, it is a potent staging of how the legacy of Nazism still permeates contemporary West Germany. This technological dystopia it suggests a latent totalitarianism in the very fabric of the modern world, an anti-modern, conservative Spenglerian vision revisited from Metropolis (1927) but also close to the Frankfurt School’s analysis of modern capitalism that would inspire the rise of the New Left in the decade to come. The stylized “bad” acting could then be seen as a self-reflexive dramatic device illustrating an alienated landscape of soulless marionettes, programmed and controlled by their respective masters.

Continuing a motif from Lang’s previous films (for instance Spione, 1928, and M, 1931) society’s legal repressive structures (police, official and undercover) and the criminal organization (Cornelius/”Mabuse” and his followers) mirror each other. The ultimate puppet master is of course Lang, his film mirroring Mabuse’s cynical theory from The Gambler in which he declares that the world and all the artistic expressions of it is all just a game.

© Michael Tapper, 2010. Sydsvenska Dagbladet 2010-09-25.