(and a few tips on what to read in between the films)

Expensive DVD boxes are one of the new gold mines of the big media corporations. But when Warner Bros. (a AOL/Time Warner company) presents so many animation classics with loads of (mostly) terrific extras as they do in the Looney Tunes Golden Collection ($54.99/volume of four DVDs) – a third volume was recently added to the series – then I cannot but reach for my credit card. The most serious reservation to the series is that the films seem to have been collected by the Looney Tunes characters themselves, i.e. in no particular order at all. What is wrong with chronology? Then you can follow the artistic development of the characters through the films. And why does Bugs Bunny get his own discs when the collection – so far – only has included a meager two Road Runner cartoons scattered among a mix of other films?

On a more positive note, you’ll get okay to perfect picture quality on all the films in the boxes. And what films then! Duck Amuck (1953), One Froggy Evening (1955), Long-Haired Hare (1949), Fast and Furry-ous (1949) and What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) are only a handful of the best titles included here. Michael Barrier, author of Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age (Oxford University Press, 2004), provides most of the useful comments to selected films. And as a tribute to genius Charles M. ‘Chuck’ Jones (1912–2002) – director of all the titles above – a 50-minute documentary predictably called Chuck Amuck (filmed at London’s Museum of the Moving Image, also sadly deceased) is included in the third Looney Tunes Golden Collection volume. I could easily go for a full-length feature by Photoplay. Still, this is a good quick stroll through his life and career, and his autobiography Chuck Amuck (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989) is still in print … so get that to know more about one of the most important artists in film history. And while you’re at it, check out Animation Journal at animationjournal.com. It is about time that animation film gets more attention in the university classroom.

Films from The Wizard of Menlo Park

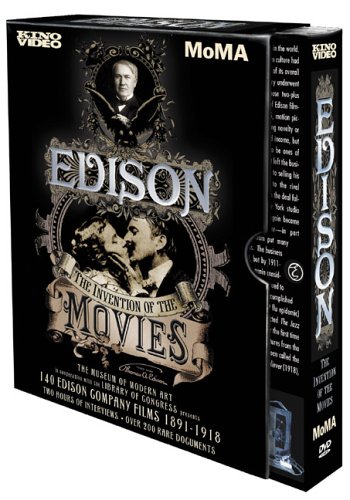

An even more expensive box ($99.99) that will surely find its audience of sc holars and students of cinema is Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and Kino on Video’s joint venture Edison: The Invention of the Movies, a collection of 140 of the company’s most important films 1889–1918 on four DVDs mixed with a total of two hours of interviews on specific titles. Charles Musser, Eileen Bowser et al. provide solid information, not on a commentary track but as introductions to various sections of films – a much better solution for this kind of material. Picture quality is mixed but, I guess, the best we can get as of now from the archives of MoMA and Library of Congress.

holars and students of cinema is Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and Kino on Video’s joint venture Edison: The Invention of the Movies, a collection of 140 of the company’s most important films 1889–1918 on four DVDs mixed with a total of two hours of interviews on specific titles. Charles Musser, Eileen Bowser et al. provide solid information, not on a commentary track but as introductions to various sections of films – a much better solution for this kind of material. Picture quality is mixed but, I guess, the best we can get as of now from the archives of MoMA and Library of Congress.

Watching the first DVD, two things are striking. The most obvious is the discrepancy between the film list on the cover and what is presented on the actual DVD itself. One title is missing (W.K.L. Dickson’s The Hornbacker-Murphy Fight, 1894) and seven others are included: Fifth Avenue, New York (James H. White, 1897), New Black Diamond Express (James H. White, 1900), New Watermelon Eating Contest (James H. White, 1900), Another Job for the Undertaker (Edwin S. Porter, 1901), The Burlesque Suicide No. 2 (Edwin S. Porter, 1902), The Interrupted Bathers (Edwin S. Porter, 1902) and Rector’s to Claremont (Edwin S. Porter, 1904). In such an important historical documentation that will be used as a reference and an instrument in teaching film, one could ask for a better index of titles and where to find them. The other is how primitive the Edison films of the 1890s appear artistically (composition, narration) compared to contemporary competitors such as Lumière and Méliès. Not any comments on that. And where are the popular Uncle Josh films by Edwin S. Porter (Uncle Josh in a Spooky Hotel, 1900; Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show, 1902 etc.)? They are not even mentioned here. Is there a Volume 2 in the making?

When Porter arrives everything changes. He starts developing more complex narrative strategies, both within the composition of the frame and in the cutting of many shots to a cohesive storyline. Although Charles Musser has written extensively on Life of an American Fireman (1902) and The Great Train Robbery (1903), both landmark films by Porter, I would like to have more in-dept comments and break-down analyses of these key films in history on the disc – maybe even in a separate section on the menu. They could even consider sacrificing a few of the films after 1910, when the Edison films definitely could not match the competition from more sophisticated film-makers, to focus more on the early years.

Still, there is an abundance of films and extras to watch, including such Porter highlights as the theatrical fortissimo take on Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1902), surreal visual effects show The Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906), political spin-doctor’s tale The ‘Teddy’ Bears (1907) and one of my all-time low-brow favorites: Trapeze Disrobing Act (1901), which is just as great for the lady’s highly original striptease act as for the two pre-Muppet Show old geezers’ animated comments from the balcony.

Highlights of Early Experimental Cinema

A constant frustration as a film student on a university in a s mall town with no cinematheque in sight and as a programmer for a university film society with limited access to the archives of film institutes was that many films were unavailable for me and my friends to see. They were just titles in the film history books, sometimes illustrated with alluring stills that just wetted the appetite for the films even more. Especially difficult to see were many of the most renowned experimental films from the 1920s and 1930. Now, at last, Kino on Video has released Avant-Garde, a two-disc collection that just about sums up all the experimental titles from both sides of the Atlantic that I have longed to watch: Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler’s Manhatta (1921), Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mechanique (1924), Hans Richter’s Vormittagsspuk (1928), Joris Ivens’ Regen (1929) and many more. Picture quality is uneven, to say the least. Wet-gate cleaning on most of them would have made a lot of difference. And why no expert commentary tracks to these historically important films? In any case, this box is a must-buy for anybody with the slightest interest in film history, and lots of great stuff still left to steal for the more ambitious film and music video directors of today.

mall town with no cinematheque in sight and as a programmer for a university film society with limited access to the archives of film institutes was that many films were unavailable for me and my friends to see. They were just titles in the film history books, sometimes illustrated with alluring stills that just wetted the appetite for the films even more. Especially difficult to see were many of the most renowned experimental films from the 1920s and 1930. Now, at last, Kino on Video has released Avant-Garde, a two-disc collection that just about sums up all the experimental titles from both sides of the Atlantic that I have longed to watch: Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler’s Manhatta (1921), Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mechanique (1924), Hans Richter’s Vormittagsspuk (1928), Joris Ivens’ Regen (1929) and many more. Picture quality is uneven, to say the least. Wet-gate cleaning on most of them would have made a lot of difference. And why no expert commentary tracks to these historically important films? In any case, this box is a must-buy for anybody with the slightest interest in film history, and lots of great stuff still left to steal for the more ambitious film and music video directors of today.

And talking about commentary tracks, they have formed quite a diverse set of genres since the early digital video years with the laserdisc format: close readings by film scholars, production history trivia by self-appointed experts, a gathering of friends from the cast and crew telling anecdotes from the production that only amuse themselves and not us etc. The ultimate spin-off is, perhaps not that surprising, the rise of mock-comments. Usually, these are made by actors being in character, such as the hockey players that made up the Hansen bros. on Slap Shot (George Roy Hill, 1977), the band members on This Is Spinal Tap (Rob Reiner, 1984) or Bruce Campbell as senior citizen Sebastian Haff as ‘The King’ on Bubba Ho-tep (Don Coscarelli, 2003) – all taking their acts one step further on the commentary track to the respective DVD releases. Number one on this alternative list must, however, be the commentary track on the Coen bros.’ 2001 DVD release of Blood Simple (1984), on which fictional scholar Kenneth Loring does a clever satire of both the nerd-expert’s trivia excesses and of the Academic Interpretation Inc.

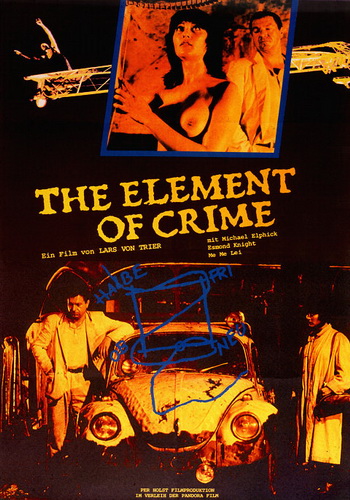

But what are we to make of Lars von Trier’s self-derogatory – even self-debasing – commentary tracks on Tartan Video’s new DVD box release Lars von Trier’s Europe Trilogy, containing his first three features, The Element of Crime (Forbrydelsens element, 1984), Epidemic (1987) and Europa (1991) plus an assortment of extras, such as his controversial exam work (an Easter egg on the Epidemic disc) from the national film school, Images of a Relief (Befrielsesbilleder, 1982)? It does not matter if you are a Trier fan or not. Switching between the parallel commentary tracks on The Element of Crime indicates that there is something rotten in the state of film culture today: on one track Danish scholar Peter Schepelern and Swedish author/film-maker Stig Björkman pays a devout, auteurist tribute to the film’s mixture of film noir, post-apocalyptic science fiction and Tarkovskyan cinematography. On the other track Trier and editor Tomas Gislason casually dismiss the very same images as pretentious film school masturbation, and Trier even mocks his critic fans by saying that one source of inspiration for him was Donald Duck’s nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie.

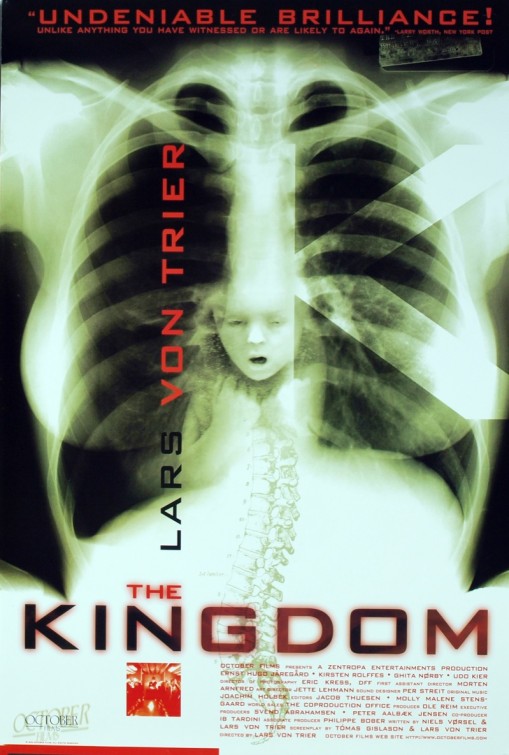

Disregarding the commentary tracks and just looking at the films themselves (all beautifully transferred to the DVD format) in the context of Scandinavian cinema, I am still struck with how different and daring they are stylistically. The national film schools, film institutes and national film funds of the last 40 years has mostly produced artless, politically correct, dreary pseudo-realism by directors with no sense of film history or talent for exploring the possibilities of the art form. Lars von Trier was – and still is – an aberration in this regard, and not a very welcome one either before his hit-series The Kingdom I & II (Riget I & II, 1994/97; released in Denmark by Zentropa/DR in an excellent box with English and other subtitles) and the international film festival favourite Breaking the Waves (1996).

still struck with how different and daring they are stylistically. The national film schools, film institutes and national film funds of the last 40 years has mostly produced artless, politically correct, dreary pseudo-realism by directors with no sense of film history or talent for exploring the possibilities of the art form. Lars von Trier was – and still is – an aberration in this regard, and not a very welcome one either before his hit-series The Kingdom I & II (Riget I & II, 1994/97; released in Denmark by Zentropa/DR in an excellent box with English and other subtitles) and the international film festival favourite Breaking the Waves (1996).

Like Bergman after his Cannes-awarded Smiles of a Summer Night (Sommarnattens leende, 1955), Trier is now loved to death. For him – used to the role of enfant terrible – the possibility of spitting in the eyes the very same cultural establishment that previously dismissed him and now welcomes him with open arms is perhaps too tempting. Only, it does not provide us who go to the director’s commentary track for some useful information with anything worthwhile.

Long Live the Cronenbergian Flesh

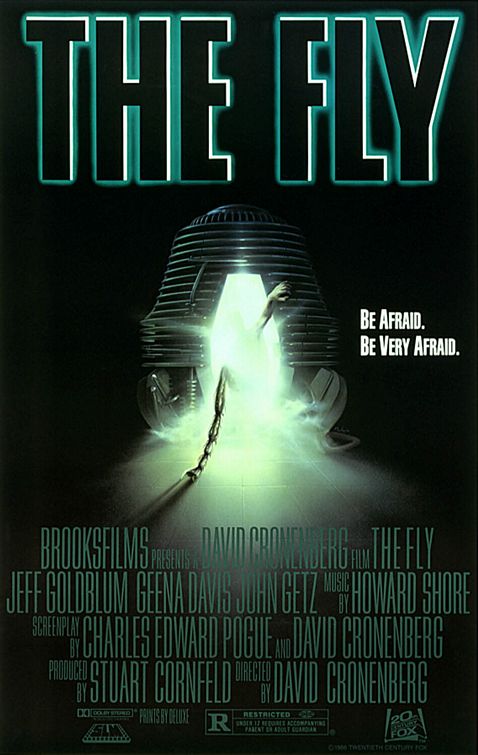

A more rewarding alternative is to buy a selection of David Cronenberg’s films on DVD with comments by the director: Videodrome (1982), Dead Ringers (1988), Naked L unch (1991) – all released by Criterion Collection – and the two-disc edition of The Fly (1986), recently released by 20th Century Fox. As witnessed by interview books, like Chris Rodley’s Cronenberg on Cronenberg (Faber and Faber, 1997) and Serge Grünberg’s David Cronenberg: Interviews (Plexus, 2005), Cronenberg is a rare example of a director who is able to put his artistic ambitions into words and one who is interested in having an intellectual dialogue with both his audience and his critics.

unch (1991) – all released by Criterion Collection – and the two-disc edition of The Fly (1986), recently released by 20th Century Fox. As witnessed by interview books, like Chris Rodley’s Cronenberg on Cronenberg (Faber and Faber, 1997) and Serge Grünberg’s David Cronenberg: Interviews (Plexus, 2005), Cronenberg is a rare example of a director who is able to put his artistic ambitions into words and one who is interested in having an intellectual dialogue with both his audience and his critics.

Starting with comments on the production history of The Fly, a project that he declined many times during his two-year work on Total Recall (eventually taken over by Paul Verhoeven after ‘creative differences’ with the producer, Dino De Laurentiis), he talks about what eventually attracted him to screenwriter Charles Edward Pogues inspired solutions to many of the silly pseudo-scientific premises of the original film made in 1958. He then continues with details of his own rewrite of the script and changes made at the set during the making of the film. Again and again he argues passionately against accusations of his film style as cold and detached and the choice of subjects as body horror exploitation with a strong undercurrent of disgust – especially for the female anatomy (Rabid, The Brood).

The Fly could not be a better argument for Cronenberg’s present auteurist position and for his use of the old science fiction concept that humans (read: white men with megalomania) create technology, and technology will then proceed to change us. This his financially greatest success this tragic love story of inventor Seth Brundle and science journalist Veronica Quaife, played by then-real-life couple Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis, ingeniously shifts the perspective between them so that we will understand their motives up until the last act, when Brundle is losing touch with his human side. Then, the point of view is all Veronica’s, and with her we fully understand the heart-breaking concept of the monster as a flawed hero from within our own culture – not just another Other threatening to break down the barriers of ‘normality’.

Emile de Antonio Renaissance

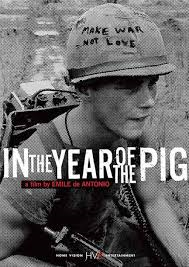

The outstanding box-office figures for documentaries such as Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) and Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me (2004) means that many class ic titles also are taken from the archive shelves to be digitalized. Emile de Antonio (1920–89) finally gets his well-deserved renaissance on DVD with New Yorker Video’s release of feature debut Point of Order (1964) and Image Entertainment’s release of the controversial anti-Vietnam war documentary In The Year of the Pig (1968). Both DVDs make good use of recorded interviews with the director on the commentary tracks. In The Year of the Pig also includes a good 1979 interview with de Antonio by June Perry Levine at University of Nebraska.

ic titles also are taken from the archive shelves to be digitalized. Emile de Antonio (1920–89) finally gets his well-deserved renaissance on DVD with New Yorker Video’s release of feature debut Point of Order (1964) and Image Entertainment’s release of the controversial anti-Vietnam war documentary In The Year of the Pig (1968). Both DVDs make good use of recorded interviews with the director on the commentary tracks. In The Year of the Pig also includes a good 1979 interview with de Antonio by June Perry Levine at University of Nebraska.

In the era of ‘embedded’ and ‘patriotic’ news, de Antonio reminds us how effective investigative, critical journalism really can be using just archive footage and interviews with a number of voices all over the political spectrum (politicians, military personnel, journalists). In The Year of the Pig also makes creative use of the soundtrack, for instance in the mix of sounds from different attack helicopters into what sounds almost as a doom-laden musical piece at the beginning of the film. No wonder Francis Coppola and sound artist Walter Murch stole the idea for Apocalypse Now (1979). That media-saturated young students are still shocked and outraged – such as mine were – by these black-and-white scenes from a war that ended 30 years ago is a credit to de Antonio’s film-making skills.

© Michael Tapper, 2006. Film International, vol. 4, no. 1, 2006, pp. 6—12.