Keywords: Wallander, Sweden, Kenneth Branagh, BBC, TV series, Ideology, Crime, Welfare State.

Keywords: Wallander, Sweden, Kenneth Branagh, BBC, TV series, Ideology, Crime, Welfare State.

Introduction: From Morse to Norse

After Inspector Morse was killed off by a heart attack in 2000, British press speculated about a replacement: an enigmatic and charismatic police that could captivate the TV audience for years, perhaps decades to come. And, by the way, one that would also be an impressive detective. About the same time Henning Mankell became a household name throughout Europe, selling millions of books about a middle-aged cop who lives on his work in the small southern Swedish port town of Ystad (population: 17,000) around the clock, drinks too much, suffers from diabetes and, yes, loves opera. Sound familiar? British media certainly thought so when talks about a BBC production of his novels about Inspector Kurt Wallander was initiated by Mankell’s film company Yellow Bird in 2006 (Smith & Sharp 2006), and although his name and the brand of the bestselling series is Wallander, Mankell’s character was quickly baptized ‘Inspector Norse’ or ‘Norse Morse’ (Unsigned 2008a, Rampton 2008, Pickles 2008; in an added twist Branagh’s next project as director was Thor).

Names mentioned for the title character have been Trevor Eve, Neil Pearson, Jason Isaacs, David Morrissey, Clive Owen and Michael Gambon (Smith & Sharp ibid). But in the summer of 2007 Kenneth Branagh went to present his film version of The Magic Flute at the Ingmar Bergman Week on Fårö – close to Bergman’s home – and met with Mankell (who is married to Bergman’s daughter Eva). The two men decided to collaborate on the project. Yellow Bird set up a deal with Left Bank Pictures and BBC Scotland. When the three-novel project and its £6 million budget were announced in a BBC press release on January 10 2008, dissenting opinions were immediately voiced questioning why British money should be invested in a Swedish author (the budget was later revised to £7.5 million, see Memorandum from Left Bank Pictures). “My main caveat is that there’s so much good, complex and diverse Scottish crime writing going on right now that I’d like to have seen BBC Scotland pick up on that,” crime novelist Ian Rankin commented (Cornwell 2008).

In the age of transnational culture production in the regional politics of the European Union, the conflict of investing in intellectual property is perhaps not unusual, but the Wallander project was furthermore going to be produced on location in Sweden, partly using a Swedish crew. This Swedish-British co-production would spend most of its money in Sweden. It would boost both the Swedish author and the crime fan tourism of Ystad, in which the stories are set and where there is already a thriving industry using Wallander as brand. As Francis Hopkinson of Left Bank Pictures stated in the press release: “These are fantastic stories set in a beautiful and rarely seen part of the world. Southern Sweden is a stunning place to film and the location will lend a magical quality to this unique production.” Wallander aimed to be Swedish in everything apart from using British actors speaking in English. One comment (Cornwell ibid) feared that the series would present a “picture postcard” Sweden with Ystad as a Midsomer Murders clone. He should not have worried. Old stereotypes die hard, and ideological warfare still hold a firm grip of the image of Sweden as the strange Other country, where life is cold, bleak and suicidal.

In the age of transnational culture production in the regional politics of the European Union, the conflict of investing in intellectual property is perhaps not unusual, but the Wallander project was furthermore going to be produced on location in Sweden, partly using a Swedish crew. This Swedish-British co-production would spend most of its money in Sweden. It would boost both the Swedish author and the crime fan tourism of Ystad, in which the stories are set and where there is already a thriving industry using Wallander as brand. As Francis Hopkinson of Left Bank Pictures stated in the press release: “These are fantastic stories set in a beautiful and rarely seen part of the world. Southern Sweden is a stunning place to film and the location will lend a magical quality to this unique production.” Wallander aimed to be Swedish in everything apart from using British actors speaking in English. One comment (Cornwell ibid) feared that the series would present a “picture postcard” Sweden with Ystad as a Midsomer Murders clone. He should not have worried. Old stereotypes die hard, and ideological warfare still hold a firm grip of the image of Sweden as the strange Other country, where life is cold, bleak and suicidal.

Sweden: Heaven and Hell

The crossfire on the welfare state project began right at its very conception at the time of the Great Depression of the 1930’s, and it came from both left and right. At the end of the century, the Green movement joined in. Due to its miracle economy and successful consensus politics, Sweden was epitomized as the ultimate example of this project. Taking control of the history of Sweden, its national narrative and mythology, was therefore of the essence to the critics. For a long time the social democratic party – in government from 1932 to 1976 – was largely in control if this narrative, making it one of progress, prosperity and modernity. But gradually it has been overshadowed by a counter-narrative of decay, misery and decline. At the end the 20th century the critics had turned the Swedish welfare state narrative from a frontier of dreams into a nightmarish wasteland.

The liberal-conservative dream of rolling back the Swedish welfare state has been the dominating critical voice both domestically and internationally. Up until the 1960s its most common counter-narrative was that the Swedish neutrality and welfare state in fact fronted for a ’mole’ communism in the Western hemisphere. For them the official version a ’third way’ between capitalism and communism was just a front for a ’pinky’ commie-wannabe or, worse, a fifth columnist state awaiting orders from Moscow. Controversy heated up as Prime Minister Olof Palme openly criticised the American war in Vietnam and had intimate relations with most socialist liberation movements in the Third World in the 1960s. At this time you didn’t have to dig deep into the conservative press to find hate-caricatures of Palme, suggesting that he was a stooge for the Soviet Union (one infamously show him with the hammer and sickle reflected in his eyes).

The dystopian narratives frequently took rhetoric and horror scenarios from popular, political science fiction novels such as George Orwell’s anti-Stalinist 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s anti-Fordist Brave New World. The fact that George Orwell was a socialist and that Huxley satirized capitalism was ignored. The overwhelming popular support for the social democratic government together with the high voting statistics was narrated as the sign of a Big Brother society in which people had turned into the mindless followers of the commands of the Party. This rhetoric was in tune with the international Cold War propaganda, frequently portraying Sweden as an over-rational dystopia where secularization had derived the population of their souls and social reform aiming for equality meant conformity and the levelling of the masses.

Two typical examples are the Italian mondo film Sweden: Heaven and Hell (Svezia, inferno e paradise, 1968) and British correspondent for The Observer, Roland Huntford’s book The New Totalitarians (1971). Between the two, they sum up most of the stereotypical images about Sweden as an exotic and titillating yet terrible place in the northern outskirts of Europe (i.e. civilization) where the government has brainwashed the population into becoming gloomy drones driven to misery and drug-abuse by promiscuity, atheism, hedonism and general permissiveness. In short, mindless Swedes ran around naked whenever possible, had tons of detached sex, got depressed, drank and/or took drugs and finally killed themselves. According to Huntford, the rationale for this – and he specifically points to sex – was that Big Brother used it as harmless outlets for disenchanted seekers of true freedom (meaning: Western democracy, which Sweden by implication had not, plus the traditional repressive structures of class, religion and morality).

Two typical examples are the Italian mondo film Sweden: Heaven and Hell (Svezia, inferno e paradise, 1968) and British correspondent for The Observer, Roland Huntford’s book The New Totalitarians (1971). Between the two, they sum up most of the stereotypical images about Sweden as an exotic and titillating yet terrible place in the northern outskirts of Europe (i.e. civilization) where the government has brainwashed the population into becoming gloomy drones driven to misery and drug-abuse by promiscuity, atheism, hedonism and general permissiveness. In short, mindless Swedes ran around naked whenever possible, had tons of detached sex, got depressed, drank and/or took drugs and finally killed themselves. According to Huntford, the rationale for this – and he specifically points to sex – was that Big Brother used it as harmless outlets for disenchanted seekers of true freedom (meaning: Western democracy, which Sweden by implication had not, plus the traditional repressive structures of class, religion and morality).

Then, in the 1960s, the new Marxist-Leninist left reintroduced the 1930s Stalinist doctrine of social fascism, by which the social democratic consensus politics masked a ‘benevolent’ totalitarianism – fascism with a social agenda. In order to explain the general consent for the social democratic consensus politics, the new left used Marxist concepts such as false consciousness, dominant ideology and hegemony – all instruments used by the power elite to goad the working-class into submission, even making them into willing collaborators of their own oppression. The keyword for the poor state of the masses in need of a revolutionary avant-garde was now alienation, but the Marxist-Leninist nightmare vision of the welfare state promising democracy, social equality and solidarity but in fact producing the very opposite were strikingly similar to the conservative propaganda.

Another anti-welfare state ideology of importance at the end of the century was the Green movement’s ecologist or eco-humanist dichotomy between community and consumerism. They evoked German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies book Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft from 1887, in which the pre-industrial agricultural community is celebrated as natural in contrast to the abstract construction of industrial urban society. In the Green crossover between the new left and classical conservatism, natural law and morality has broken down in the modern world, consumerism has replaced community, again programming the alienated masses into a false consciousness. They aimed for different goals, but liberal-conservative, Marxist-Leninist and green criticism against the welfare state frequently overlapped and used the same stereotype images of Sweden as a democratic idyll on the surface, concealing the ’true’ state of totalitarianism and quiet desperation of the indoctrinated masses. Social reform in all areas of society, from corporal punishment of children to abortion and to the school and penal systems, was therefore demonized as threats of the permissive society. This played effectively into media horror narratives and moral panics about criminality and drug abuse among juveniles, claims of record statistics in suicide rates and alcoholism, and controversy about pornography and sexual perversity (see Lennerhed 1994:89-98).

The Sjöwall & Wahlöö Connection

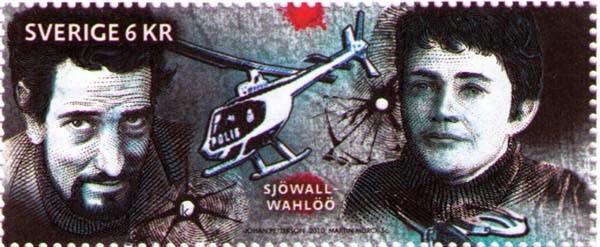

The most popular crime fiction series about Sweden as masked totalitarianism was the ten novels 1965-75 on Martin Beck and his team at the National Murder Commission by Marxist-Leninist journalists Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. In presenting their police novels as an instrument for the “analysis of a bourgeois welfare state in which we try to relate crime to its political and ideological doctrines” (Sjöwall & Wahlöö 1978:98) they invoked the theory of social fascism but frequently touched on liberal-conservative and ecologist criticism. Wahlöö alone had already written a kind of sequel in his two science fiction police novels about Inspector Jensen’s adventures in Brave New Stockholm on the verge of a communist revolution: Murder on the 31st Floor (Mord på 31:a våningen, 1964) and The Steel Spring (Stålsprånget, 1968).

As can be witnessed by the success and positive media reception, Sjöwall & Wahlöö had a crossover appeal in all the anti-welfare state camps. From 1965 to the millennium they were by far Sweden’s most successful crime fiction export. Four of their novels have been adapted subjected to film adaptations outside Sweden, notably the 20th Century Fox-produced The Laughing Policeman (1973), the Hungarian-German-Swedish The Man Who Went Up in Smoke (1980), the German Kamikaze 1989 (1982; based on Murder on the 31st Floor) and the Dutch production Beck (1992; based on The Locked Room). In Sweden eight novel adaptations were produced 1967-1994 and three Beck film series of eight features each made in 1997-98, 2001-02 and 2006-07 using some of the main characters from the novels (at least three new features are in production now).

Sjöwall & Wahlöö’s project was to stress the ambiguousness of their subtitle Report of a crime. Being Marxist-Leninists, the authors saw crime in sociopolitical terms: as the logic outcome of a criminal class society. But comments to that effect were frequently dropped into monologues or brooding afterthoughts, leaving the main part of the narratives quite similar to the urban nightmares of reactionary mainstream crime fiction, say Dirty Harry. Part of their attraction was their contrast of the seemingly idyllic Sweden with the horrible murders, vice and crime that resided beneath the surface – the nation of tourist brochures versus Sweden as harsh reality. No coincidence then that the series, starting with Roseanna, opens at a beautiful place along Göta Kanal, where tourists frequently go by on channel boat cruises. In a stark contrast to the picturesque setting, the body of the sex-murdered American tourist of the title is fished out of the muddy waters. A striking image of crime as the return of the repressed, all the more symbolic since the display of her body is witnessed by a Vietnamese tourist.

criminal class society. But comments to that effect were frequently dropped into monologues or brooding afterthoughts, leaving the main part of the narratives quite similar to the urban nightmares of reactionary mainstream crime fiction, say Dirty Harry. Part of their attraction was their contrast of the seemingly idyllic Sweden with the horrible murders, vice and crime that resided beneath the surface – the nation of tourist brochures versus Sweden as harsh reality. No coincidence then that the series, starting with Roseanna, opens at a beautiful place along Göta Kanal, where tourists frequently go by on channel boat cruises. In a stark contrast to the picturesque setting, the body of the sex-murdered American tourist of the title is fished out of the muddy waters. A striking image of crime as the return of the repressed, all the more symbolic since the display of her body is witnessed by a Vietnamese tourist.

Their portrayal of ’the system’ as a playing ground for inept bureaucrats and political careerists corresponds with the American backlash politics, diverting the critical eye from capitalism and the conservative social elite to misguided liberal reformists. Early ecologism is visible in their descriptions about hollow consumerist frenzies during Christmas and suburbs as apocalyptic concrete jungles. Sometimes the urban nightmare is set against a nostalgic and ’lost’ idyllic image of rural or small-town Sweden, most prominently in the 1974 Cop Killer. The following 1975 novel The Terrorists closes in a Stockholm besieged by organized crime, terrorism and violent demonstrations. The novel also features the killing of the Swedish Prime Minister eleven years before the fact. Here, Sweden is clearly heading for the totalitarian state of the Inspector Jensen dystopia.

The first two novels focuse on Martin Beck, an aging, tired and slightly ill Inspector. He is competent though hardly a Sherlock Holmesian genius, but he is no match for the escalating violence and savage crimes of the welfare state. In the third novel, the 1967 The Man on the Balcony (Mannen på balkongen), super-cop Gunvald Larsson is therefore introduced. Initially Larsson comes out as a single-minded brute, a comical version of the colonial super heroes in the reactionary novels by Sax Rohmer or Øvre Richter Frich he reads in his spare time. Gradually, there is a shift of balance from Beck to Larsson. Beck grows more and more distant from his work to contemplate his possible resignation from the force so he can start anew with his Marxist-Leninist girl-friend Rhea. Larsson is therefore remodelled as a true-blue action hero, proving to have the right stuff in a time of violent turmoil, terrorism and organized crime.

Yvonne Tasker (1993:97) has proposed that “nationhood and masculinity are crucial terms with most war films, indeed combat films generally,” and the Swedish police procedural tradition of Sjöwall & Wahlöö is a good example of that. Both Inspector Jensen’s and Martin Beck’s ailing bodies are obvious metaphors for society’s ailments. The parallels are almost overstated as Jensen in The Steel Spring finally gets his operation while his home country is cured by a communist revolution, and Beck’s stomach problems fade away in when bedded by Rhea under a poster of Mao Zedong. Their successors, however, has no such cure to look forward to. Larsson is of another stock, like the colonial warriors past and present an idealized masculinity of firmness that never back down or bend over – a body that, like James Bond’s, Harry Callahan’s and John Rambo’s, can take anything thrown at him. His physical similarity to the fictional heroes of his preferred reading, say Aryan übermensch Jonas Fjeld in Frich’s racist novels, is striking; he is blonde, tall, muscular, determined, arrogant and self-reliant (Tapper 2009a and 2009b).

The legacy of these two cops is clearly visible in the most successful post-Sjöwall & Wahlöö crime novels. Larsson is the main influence on Olov Svedelid’s 27 novels about hard-nosed cop Roland Hassel (1973-2004, eleven film adaptations 1986–2000) and Jan Guillou’s ten novels about super spy Carl Hamilton (1986-95, five film adaptations 1989-98). Beck has been the model for a whole generation of aging, ill and brooding Swedish police inspectors. Two internationally well-known and best-selling examples are Håkan Nesser’s cancer-ridden and grumpy old Van Veeteren (ten novels 1993–2003, three TV series 2001-03 and six films 2004–05) and Henning Mankell’s diabetes-ridden, middle-aged and insomniac Kurt Wallander (ten novels 1991-2002 including Before the Frost, six TV series, 17 feature films – and twelve more in production at the time of writing). Like Sjöwall & Wahlöö, Mankell have his roots in the Marxist-Leninist new left of the 1960s, but his 1990s is a strikingly different landscape. Although the welfare state is but a fading ghost of times passed, Mankell seems unsure (unable? unwilling?) how to address the new age, so he mostly continues his attacks against the dying old enemy.

The period 1975–91 was a transition period from welfare state industrialism to a post-industrial economy with neoliberal features. After some years of dynamic financial expansion in the 1980’s, the new miracle economy collapsed in a severe depression the very same year of the first Wallander novel: 1991. By then the 1960’s Marxist-Leninist left was gone as a political force, having never gained more than a few per cent of the votes to the parliament in any election. Rather, the new forces of radical politics came from the extreme right, like the racist party Ny Demokrati (’New Democracy’, in parliament 1991–94) or neo-Nazi organisations such as Vitt Ariskt Motstånd (’White Aryan Resistance’). When Kurt Wallander wakes up in the early hours of a cold day in January to take on the first case of the series in Faceless Killers, his landscape is bleaker with something more than crime. While the world and everybody else seems to have moved on, Wallander – perhaps like Mankell – is left standing alone in limbo, abandoned by everyone. Even his family has left him. Soon his ex-wife takes up with a man in a higher social position, “a golfer” as he is referred to in the Branagh TV series.

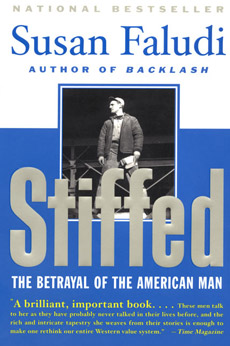

Wallander is stiffed. He could serve as text book example of Susan Falud i’s 1997 report on the ’betrayed male’, a socially and sexually marginalized man unable to navigate in the post-modern world. Only his work gives him a sense of purpose and meaning. His private life is in chaos, having regressed into a state of irresponsible infantilism, self-pity and awkwardness. Wallander’s home is cluttered with old pizza cartons, beer cans, withered plants and dirty laundry. In this garbage dump he called to new assignments again and again after having fallen asleep on the couch in front of the TV or listening to an opera on the stereo. Occasionally he passes out after a drunken stupor longing for the company of a woman or dreaming about his impossible romance with the elusive Baiba Liepa, the widow of a murdered Latvian colleague. The telephone usually cuts his much-needed rest short, calling him to yet another grisly murder site or to boost his already heavy burden of guilt – for having missed yet another meeting or birthday or visit to his father. And as always, he resolves to change. Then he immediately postpones this decision to another day. He is a man who constantly keeps busy while life passes him by.

i’s 1997 report on the ’betrayed male’, a socially and sexually marginalized man unable to navigate in the post-modern world. Only his work gives him a sense of purpose and meaning. His private life is in chaos, having regressed into a state of irresponsible infantilism, self-pity and awkwardness. Wallander’s home is cluttered with old pizza cartons, beer cans, withered plants and dirty laundry. In this garbage dump he called to new assignments again and again after having fallen asleep on the couch in front of the TV or listening to an opera on the stereo. Occasionally he passes out after a drunken stupor longing for the company of a woman or dreaming about his impossible romance with the elusive Baiba Liepa, the widow of a murdered Latvian colleague. The telephone usually cuts his much-needed rest short, calling him to yet another grisly murder site or to boost his already heavy burden of guilt – for having missed yet another meeting or birthday or visit to his father. And as always, he resolves to change. Then he immediately postpones this decision to another day. He is a man who constantly keeps busy while life passes him by.

The very first day of his fictional life is typical. Wallander rushes between the murder site, the police station, witnesses to interrogate, relatives to the murder victims and his grouchy father – the painter who is constantly remaking the same lonely, barren landscape. At six pm, he notices that he has forgotten to eat and, though he has promised to go on a much-needed diet, he drives in to grab a meal at his regular fast-food stand. After gulping down a hamburger and fries, he gets diarrhoea. In the toilet, he notices his need for fresh underwear. During next day’s work we notice that this procedure is repeated; the routines of constant stress.

Of the young idealist policeman in the 1960s only a ruin is left in 1990. The firm and muscular body of the past has withered away under malnourishment and diabetes, and he has an empty, despairing soul to match. Wallander is a monument of the diseased consumer society, working overtime and fattening his body with a cholesterol overload. Like Sweden’s way from record growth to record crisis, from model society to monster society, he is headed for collapse. His rhetorical outcries about what is happening to the world and to his country, is not as much nostalgia for the lost welfare state as a cry for the lost future of yester day – the 1960’s promise of another an better world, perhaps Mankell’s wish for the communist utopia never fulfilled (see Ferguson & McKie 2008). His cries are never answered. Like Ingmar Bergman’s priest in Cries and Whispers (Viskningar och rop, 1973) his life is one endured on a dark and mean earth under an empty, cruel heaven.

day – the 1960’s promise of another an better world, perhaps Mankell’s wish for the communist utopia never fulfilled (see Ferguson & McKie 2008). His cries are never answered. Like Ingmar Bergman’s priest in Cries and Whispers (Viskningar och rop, 1973) his life is one endured on a dark and mean earth under an empty, cruel heaven.

The original choice for Wallander on film and TV, Rolf Lassgård, is probably the one most Swedes thinks of as the true incarnation. His natural rotundity and fearless method acting willingness to expose even the most pathetic and unattractive sides of the character challenges our sympathies. His Wallander is essentially a bumbling big baby not fit for much else but his work. Krister Henriksson’s older and leaner Wallander is more of a standard TV Inspector: quiet, resolved,  efficient but featureless. He is also beyond Lassgård’s emotional and despairing Wallander, who like a modern Christ martyrs himself through his everyday Golgata of unspeakable crimes and almost dies for our sins each time. Henriksson is Wallander getting old and detached, especially in the 2009 series based on original scripts only, and he aim for a sheltered life with his trusty dog in his house by the sea – a development hinted at in the last two novels.

efficient but featureless. He is also beyond Lassgård’s emotional and despairing Wallander, who like a modern Christ martyrs himself through his everyday Golgata of unspeakable crimes and almost dies for our sins each time. Henriksson is Wallander getting old and detached, especially in the 2009 series based on original scripts only, and he aim for a sheltered life with his trusty dog in his house by the sea – a development hinted at in the last two novels.

Branagh is somewhere in between the two. Like Lassgård’s Wallander, he takes every crime personally, often leaving the scene of a crime or an interrogation emotionally drained and devastated. He cries, is enraged at times, but mostly he is quietly brooding over a glass of wine. In stressing the insomnia, the BBC Wallander half-heartedly points to the possibility that the surreal crimes – a modern Indian warrior avenging sex-crimes, a murderous sect of IT terrorists, a psychopathic transvestite – are all figments of the main character’s nightmare hallucinations. No wonder then that Wallander is losing his grip. If things like these can happen in a small town like Ystad, what about London or the rest of the world? Had Mankell elaborated on this motif, the hyperbolic qualities of his novels could be rationalised,  and it could even open for the possibilities of a metatextual criticism of the cop fiction and its anxieties (like the intriguing Insomnia, 1997/2002). But no such reading is really validated by the text.

and it could even open for the possibilities of a metatextual criticism of the cop fiction and its anxieties (like the intriguing Insomnia, 1997/2002). But no such reading is really validated by the text.

Like most cop shows of recent years, Wallander is filmed in a traditional (or canonical) realism spiced with incidental features of intensified continuity (rack focus, shaky-cam) and meant to be taken both as a symbolic drama (tragedy, epic) and as a realist narrative representing genuine insights to modern crime and police work. Since the crime genre – also including crime journalism – is in so close contact with contemporary anxieties it is perhaps the most telling popular culture phenomenon in which, to quote Oliver Stone’s W. (2008), “perception is reality”. But as our perception of crime and police work is not guided by our own first hand intimate knowledge or experience. Most of us are left to navigate the treacherous waters of postmodern media infotainment where the borders are constantly blurred between news journalism, docudrama, reality soaps and cop shows. The increasing collapse of crime fact and crime fiction into crime faction has been described in several recent studies (see for instance Leishman & Mason 2003, Macek 2006, Lee 2007).

I Am Sidetracked – Yellow/Blue

Unlike the international adaptations of Sjöwall & Wahlöö, the 2008 British Wallander series did not transplant the narratives into another setting (like the American The Laughing Policeman, set in San Francisco) or make the fictional universe an abstract landscape of Everyman in Neverland (Kamikaze 1989). This was expressively stated to be a series depicting Sweden, thereby also depicting the legacy of the welfare state that Mankell targets in his novels. The subject is mostly stressed in episode one, based on the fifth novel Sidetracked but continued in the two following episodes: Firewall (based on the eighth novel) and One Step Behind (based on the seventh novel).

Already from the start Sweden-as-nightmare is evoked in the blurred and distorted images of a yellow rape field against a blue sky to the sound of ominous music on the soundtrack. Like the satirical opening shots of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), this beautiful summer day in paradise is undercut by a premonition of horrors to come. Cut to an establishing shot in focus. We see a dark-skinned girl march across the rape field. Inspector Wallander is summoned by the farmer and goes out to talk to her. As he approaches, he takes ou t his ID to reassure her, but the effect is quite the opposite. She gets agitated, pours gasoline over herself and ignites it. Wallander watches in horror as the yellow flames burst into the blue sky.

t his ID to reassure her, but the effect is quite the opposite. She gets agitated, pours gasoline over herself and ignites it. Wallander watches in horror as the yellow flames burst into the blue sky.

Taking the colours from the Swedish flag, the introductory images strikes a chord strikingly similar to the opening of Sjöwall & Wahlöö’s first Beck novel: the idyllic Swedish summer landscape of tourist brochures revealed as the landscape of death and despair – the urban nightmare transplanted to a rural Garden of Eden. With her dark skin, the woman is coded as an immigrant, perhaps a refugee. Her spectacular act of suicide evokes memories of the Vietnamese Buddhist monks, burning themselves to death in protest of the war in the sixties. Is she perhaps protesting inhuman immigration laws of Sweden in 2008? The truth turns out to be far worse. Wallander – curiously passive, not even attempting to save her life – could stand in for the nine o’clock TV news audience. Then again, considering the national context he could also be the prototypical Swedish drone.

Cue the credit sequence. The yellow-and-blue-motif continues in the yellow letters spelling WALLANDER filling the screen. A haggard and scruffy Kenneth Branagh stares with a gloomy look at us from a blue-on-black background while Emily Barker in an excerpt from her song “Nostalgia” sing “shadow lights/across northern skies/cut my blue heart in two.” Cut to the port-mortem. Wallander meets with his colleague Nyberg and police pathologist Dr. Malmström:

Nyberg: [She was] probably only fifteen.

Wallander: What could drive her to do that?

Nyberg: What the girl did was a completely unnatural act. Everything in her mind and body would be screaming against it.

Wallander: Fifteen…

Nyberg: It’s like these kids who self-harm now. (Turning to Malmström) What was that boy you were telling me about?

Malmström: A seven-year old tried to cut his thumb off. Had a five-year old in here recently who tried to put his eyes out…At least, that’s what it looked like.

Wallander (looking at close-up stills of the girl’s burned body): What kind of world are we leaving a fifteen-year old girl as she wants to burn herself to death?

Driving home through dark streets he sees youngsters fighting in the streets, one kicking another lying on the pavement. If anything, this is the epitome image of youth violence in popular imagination. Later in the night somebody – a teenage boy masked as an Indian warrior, as it turns out – kills and scalps the Ex-Minister of Justice, Wetterstedt. The killing is preceded by Wetterstedt watching a talk show with himself as the main guest, flippantly discussing the 1986 murder of PM Olof Palme. He snickers at his studied TV-show line “I think the world recognizes that Sweden stands for a little more than just Björn Borg, ABBA and a bit of skinny-dipping in mountain lakes”. Wetterstedt then rambles on rather incoherently about the dismantling of the Swedish model as a process of “opening up” the nation so it can “join the world”. He seems to be addressing a closed dictatorship like North Korea, when in fact Sweden during the welfare state years was one of the most open, politically extrovert and internationally engaged nations in the world.

The association of Sweden, teenage suicide, self-harm, violence, permissiveness (skinny-dipping) and a totalitarian welfare state has been set up. This is a country in which “a completely unnatural act” takes place in the bosom of nature, in the splendour of a beautiful summer day. Dr. Malmström and Nyberg state that this is just one of numerous cases – unnatural acts in an unnatural country. The curious inclusion of skinny-dipping as part of the perception of Swedishness goes back to film history, the genre of summer films (Summer Interlude/Sommarlek, The Summer with Monika/Sommaren med Monika et.al.) in which the passion of young lovers is celebrated as a brief and intense utopia matching the beauty of the short Nordic summer. Most particularly it is referring to the classic One Summer of Happiness (Hon dansade en sommar, 1951), a world-wide succèss de scandale in which the lovers skinny-dip in a lake and then make love (not in the mountains though) before the girl is tragically killed in a car accident – a death-as-punishment-for-permissiveness-scenario long before the slasher films.

The smug Wetterstedt personifies this dark legacy of sex and social reform. When he goes out into the summer night under a streamer in Swedish colours waving against dark skies and is killed by an axe in the head, this is clearly a symbolic act of vengeance directed against the roots of Sweden’s perverse condition. This is foreboded in Wallander’s meetings with investigative journalist Lars Magnusson. He reveals that Wetterstedt regularly received prostitutes delivered to his door and had been accused of sexual sadism  by at least one of them. The case was dismissed as he got protection from the political establishment by their trusty watchdog, vice squad DCI Hugo Sandin. When told about the scalping, he immediately associates the perpetrator with Indian warriors taking scalps as sacrifices to free other souls. Rather than simple revenge, the motive behind the murder is a spiritual one, taking back the souls of children raped by a welfare state whose perversity is embodied by a predatory old guard of paedophiles.

by at least one of them. The case was dismissed as he got protection from the political establishment by their trusty watchdog, vice squad DCI Hugo Sandin. When told about the scalping, he immediately associates the perpetrator with Indian warriors taking scalps as sacrifices to free other souls. Rather than simple revenge, the motive behind the murder is a spiritual one, taking back the souls of children raped by a welfare state whose perversity is embodied by a predatory old guard of paedophiles.

For a Swedish audience the revelation of Wetterstedt’s’s hidden life smacks of the 1970’s ‘Geijer Affair’, in which the social democratic reformist and Minister of Justice Lennart Geijer was accused of having sex with under-aged prostitutes (politicians from other parties were also under suspicion). The case was dismissed, but the affair is still investigated in recently published books and articles and there are theories about a cover-up involving high police officials. For an international audience, however, the underlying message is spelled out when Wallander interrogates the retired Sandin:

I am a patriot. I love this country – openness, fairness, sexual liberation, the social experiment…. Well, Wetterstedt was part of that, and it was my job to keep him in the clean. My job then, your job now… I was the janitor. I had no choice.

By then the axe murderer has claimed new victims, and Wallander is hot on the trail of the paedophile ring. However, little does he know that Sandin is actually the main supplier of foreign girls, keeping them locked up in his wine cellar until delivery. This subject was more in tune with the zeitgeist when the novel was written in 1994–95, when the paedophilia panic (sometimes including wild scenarios of Satanism and ritual killings) was at its media peak all over the Western world. Here it is invoked as the result not of the Swinging Sixties in general – I have yet to see a British film blaming Harold Wilson’s Labour government, Benny Hill or James Bond for causing paedophilia, self-mutilation and suicide – but of a politics striving for social justice, equality and sexual liberation. Not even the most virulent anti-Thatcher films in the 1980’s pictured her neoliberal politics as the cause of sexual perversion or mental illness with epidemic proportions. Yet not one of the critics – British or Swedish – thinks of the ideological subtext of Wallander as bizarre, hyperbolic or even curious when it comes to depicting the Swedish welfare state. It is simply a given fact.

“What You Got Is Your Painting”

In the final scene of Sidetracked, Wallander – just having shot and arrested the avenging teenager in Indian warrior masking – seeks console from his aging, detached father. He breaks down, cries and repeatedly sobs “Dad, I can’t do it anymore”. His dad, stops working, turns around and tells a story about when Kurt was small and frequently asked his work – the never-ending remaking of the same picture every day. He explains that he for a time started each day trying to paint something else, but still ended up doing the same landscape repeatedly. The moral of the story he then concludes is: “What you got is your painting. I may not like it. You may not like it. But it is yours!” We see his portrait of the barren, unforgiving landscape in full; the true spiritual wasteland revealed underneath the illusion of a lush paradise in the opening shots.

This image represents Mankell’s outlook of Sweden and the repeated remake the repetitious nature of his signature work: remaking the same scenario repeatedly to bring home his argument, using the crime genre as dystopian landscape. Even Wallander himself, having the same three-day beard bristle, ruffled clothes and blood-shot eyes throughout the series, is stiffed and frozen on the same spot in life. And like so any other post-modern horror and crime narratives, this is a never-ending repetition of the same nightmare. The following episodes again present us with murderous, self-destructive, empty and despairing youths in idyllic opening shots.

Firewall opens with two teenagers covered in blood walking away from a taxi, the driver lying murdered in his car at a beautiful tourist spot outside Ystad. During the interrogation, the main suspect mocks Wallander with a leering indifference to her crime. Later, she escapes but is found burned to death when sabotaging a power station as part of an IT terrorist scheme. The initial murder was triggered by a chance meeting with the father of a boy who raped here three years earlier but is otherwise completely unrelated to the plot. The final episode, One Step Behind, has an even more contrived story. It opens with the shooting of three young people dressed up as 18th century aristocrats, having a picnic in the forest. Shortly afterwards Wallander’s colleague Svedberg is found murdered. Eventually the killer is unmasked as a young transsexual psychopath with the strange motive of killing happy people out of jealousy of his/her lover Svedberg’s love for Wallander.

Unprovoked or just mindless youth violence has been a common post-WWII folk devil in crime fiction as well as in crime journalism and a corner stone in the urban nightmare scenario. Recently, British media reports of knife crime by hooded ‘street rats’ spiralled into a moral panic (Barkham 2005). Wallander will not cause any new outbreak, but it is a thread in a larger fabric of narratives that since the late 1960s has been severing all connections bet ween crime and any social or psychological context in the present in order to associate it with a metaphysical evil originating from the social policies and the permissiveness of the welfare state in the past.

ween crime and any social or psychological context in the present in order to associate it with a metaphysical evil originating from the social policies and the permissiveness of the welfare state in the past.

Unlike the dominating crime narratives of the past, order can never be restored; there is no bright future, no world in sight holding the promise of delivering us from crime. Quite the contrary, as criminologist Magnus Hörnqvist (2007:137-138) states in an essay, the criminal and in particular the psychopath has become the perfect enemy in a time obsessed with the notion of radical evil. Like a small-scale terrorist, he can be anybody anywhere, an enemy from within to manipulate in the politics of fear. Although Mankell might claim to have another agenda, his crime narratives play effectively into this politics, as can be witnessed by the 2008 Wallander series. Here, the world is beyond hope, beyond progress. All that is left is a tired and sick police officer locked in eternal battle with the sick criminals of a sick society.

© Michael Tapper, 2009. Film International, vol. 7, no. 2, 2009, pp. 60–69.

Contributor details

Michael Tapper is the former editor-in-chief (1998-2002) of the Swedish film journal Filmhäftet that transformed in 2003 to the English-language Film International. He signed up with Intellect in 2005 and remained on the editorial board until the end of the year. Since 1988 he has worked on the Swedish national encyclopedia, Nationalencyklopedin, and since 1999 he has worked as a film critic at daily Sydsvenska Dagbladet. He has contributed to several journals and anthologies and is currently working overtime in his home – about forty kilometres from Ystad – to finish his much-delayed dissertation on Swedish crime fiction 1965-2007.

References

Barkham, Patrick (2005) ’How Can a Top Can Turn a Teen into a Hoodlum’, The Guardian, 14 May.

BBC Press Release (2008) ’Wallander – Kenneth Branagh in Major New Drama Adaptation for BBC One’, 10 january.

Cornwell, Tim (2008) ’Meet TV’s New Inspector Morse … He’s Grumpy, a Big Drinker and, oh yes, He’s Swedish’ The Scotsman, 11 January.

Ferguson, Euan & Robin McKie (2008) ’The Man Behind Wallander’, The Observer, 14 December.

Hörnqvist, Magnus (2007) ’Psykopatfabriken. Det olyckliga äktenskapet mellan kriminalvård och psykopatforskning’ (’Psychopath Factory: The Unhappy Marriage of Correctional Care and the Research on Psychopathology’) in Hanns von Hofer & Anders Nilsson (eds.) (2007) Brott i välfärden. Om brottslighet, utsatthet och kriminalpolitik (’Crime in the Welfare State. About Crime, People at Risk and Crime Politics’) Stockholm: Department of Criminology, s. 123-143.

Lee, Murray (2007) Inventing the Fear of Crime. Criminology and the Politics of Anxiety Cullompton & Portland: Willan Publishing.

Leishman, Frank & Paul Mason (2003) Policing and the Media: Facts, Fictions and Factions London: Willan Publishing.

Lennerhed, Lena (1994) Frihet att njuta. Sexualdebatten i Sverige på 1960-talet (’The Freedom of Pleasure. The 1960s Sex Debate in Sweden’) Stockholm: Norstedts.

Pickles, Anne (2008) “Inspector Norse” News & Star, 6 December.

Macek, Steve (2006) Urban Nightmares: The Media, the Right, and the Moral Panic Over the City Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press.

Memorandum submitted by Left bank Pictures, published in October 2008 at the UK parliament’s Publications & Records.

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmcumeds/memo/bbc/uc1402.htm (accessed 01/02/2009).

Rampton, James (2008) “Kenneth Branagh: The Stunning, Troubled World of the ‘Norse Morse’” The Daily Telegraph, 31 October.

— ([1967] 1978) ”Kriminalromanen som samhällsskildring” (“The Crime Novel As Social Report”) pressrelease from publishing company Norstedts reprinted in The Swedish Crime Writers’ Association’s (Svenska Deckarakademin) anthology Brottslig blandning (Criminal Mix) Stockholm: Bokförlaget Plus.

Smith, Alex Duval & Rob Sharp (2006) ’Just What We Need Instead of Miserable Morse… a Gloomy Swedish Detective’ The Observer, 2 July.

Tapper, Michael (2009a) ’Dirty Harry in the Swedish Welfare State’ in Andrew Nestingen & Paula Arvas (ed.) Criminal Scandinavia: Nordic Crime Fiction Cardiff: University of Wales Press (forthcoming).

— (2009b) ’Hans kropp – samhället självt: En typology för svenska mordspanare på ålderns höst’ (’His Body – Society Itself. A Typology of Aging Swedish Homicide Inspectors’) in Gunhild Agger & Anne Marit Waade Den skandinaviske krimi som medieprodukt.

Tasker, Yvonne (1993) Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema London & New York: Routledge.