I have recently learned that many visitors at my web site – perhaps most of you – are from countries other than Sweden. Since most of my fellow countrymen are more or less fluent in English my blogs about films and, occasionally, books that I have not covered in other texts plus my reviews written exclusively for this site will therefore be written in Shakespeare’s tongue from now on. However, my archive of more than 1 600 texts, soon to reach back to 1984, are mostly in Swedish, and it is a task far too great to translate them all. There are other means – hardly perfect, I know – for those of you who want to read them. Now, on with the show.

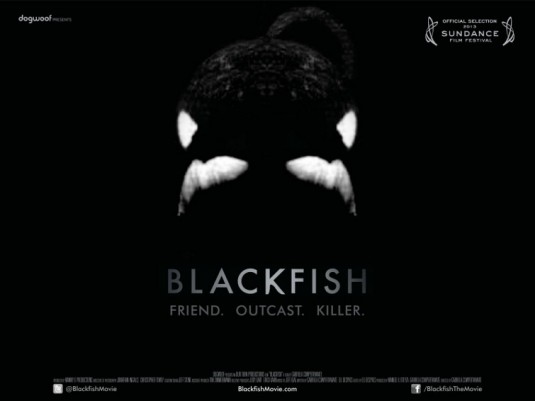

Since I was a kid I have stayed out of zoological parks, the only exception being a visit to SeaWorld in Orlando with my wife and kids more than ten years ago. For some reason I convinced myself that fish and sea mammals were not like the elephants, tigers or polar bears I have seen wither away in traditional zoos. They seemed to have fun, playing with those nice trainers and keepers. After a home screening of Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary Blackfish (2013, Dogwoof) we realized that our visit had been a serious case of self-deception – with the full support of the SeaWorld propaganda, no less.

The film is mostly about the male orca Tilikum, who has been involved in the death of three people at SeaWorld. Like a crime novel, Blackfish portrays the backstory to these tragic events culminating with the death in 2010 of star trainer Dawn Brancheau. We learn that the trainers and keepers at SeaWorld have very little, if any, knowledge about the whales they are handling. Rather, SeaWorld encourage them to fake their expertise by relying on “facts” given by the company whenever visitors express their concern about the well-being of the whales.

The official story is that the whales love to interact with their trainers and to perform in front of an audience. In order to support this narrative, SeaWorld makes a number of deceitful claims. For instance, that orcas live longer in captivity than in the wild and that the dorsal fin collapse seen in captive male orcas is a normal variation. Both are shown by whale experts to be outright lies as orcas in the wild have the same life spans as humans while orcas in the parks rarely live to be older than forty years. Dorsal fin collapse is also a rare condition outside of parks like SeaWorld. Whale experts considers this to be the sign of stress and mental unbalance that define the bad conditions under which the captive orcas live.

There are very few recordings of wild orcas being a threat to human life. Most of the incidents analysed has concluded that they probably are about misidentifications of prey, i.e. confusing humans with prey such as seals. There are, however, a staggering amount of recordings of captive orcas injuring and even killing humans since the 1960s. Tilikum is the most obvious example, and his miserable life from being captured as a young calf outside Iceland to his three killings of humans at SeaWorld is a testimony of the need to close down these parks. Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary has, unsurprisingly, been attacked by SeaWorld as “inaccurate and misleading”, but at no point have they been able to disproof any of the claims made by the film. They have also refused to participate in a public discussion with the director about the issues raised by her film.

Blackfish is impassioned and it has an agenda, but at no point does the film try to hide this. On the contrary, it is from start to the finish a film to make us think twice about paying to see captive animals do circus tricks for our amusement. Rightly so, as it is supported by experts, ex-trainers and facts galore. Furthermore, it is a thriller with a tragic twist about a wild orca getting his life destroyed by captivity. An unforgettable film using a mix of archive material, SeaWorld infotainment and interviews to make a solid case.

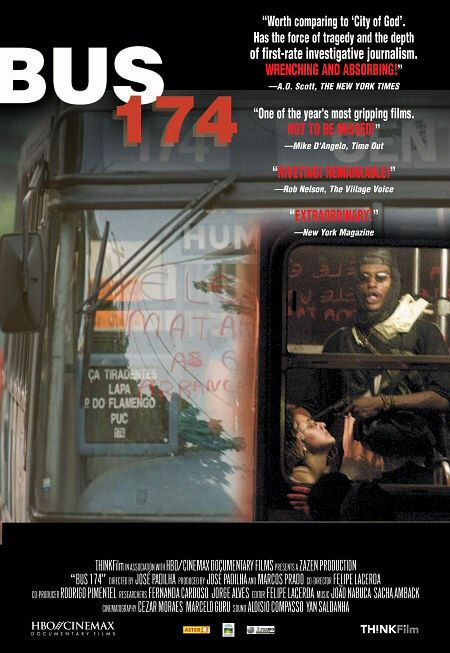

Before Brazilian director José Padilha made the 2014 dumbed-down ROBOCOP remake and the fascist police recruitment films ELITE SQUAD I (2007) and ELITE SQUAD II (2010) he actually had some talent as a documentary filmmaker. His multiple award-winning Bus 174 (2002, Metrodome) is a heart-breaking elegy over a Sandro di Nascimento, who hijacked a bus and took the passengers as hostages in Rio de Janeiro, June 12 in 2000. Millions of TV-viewers in Brazil only saw a drug-addict doing a crazy stunt for apparently no rational reason what so ever as he never expressed any demands. When the drama ended in tragedy after four and a half hours it soon faded out as a news story, but the film tracks down the backstory.

Before Brazilian director José Padilha made the 2014 dumbed-down ROBOCOP remake and the fascist police recruitment films ELITE SQUAD I (2007) and ELITE SQUAD II (2010) he actually had some talent as a documentary filmmaker. His multiple award-winning Bus 174 (2002, Metrodome) is a heart-breaking elegy over a Sandro di Nascimento, who hijacked a bus and took the passengers as hostages in Rio de Janeiro, June 12 in 2000. Millions of TV-viewers in Brazil only saw a drug-addict doing a crazy stunt for apparently no rational reason what so ever as he never expressed any demands. When the drama ended in tragedy after four and a half hours it soon faded out as a news story, but the film tracks down the backstory.

The investigation into Sandro’s motivation for the hijacking soon becomes a portrait of the innumerable street kids from the favelas who live their lives begging and stealing. At night they become prey to cops and fascist militias who see them as vermin and treat them accordingly. Many kids disappear or are found killed in the streets every year, but hardly any of these murders are investigated as clues would lead to the police force. Mostly, the legal system as well as the wealthier classes just simply ignore them and treat them as if they did not exist. Add to that the kids’ upbringing in poverty and domestic violence, making them take to a life in the streets.

Sandro witnessed the murder of his mother, a trauma one social worker who knew him says he never got over. Like so many other street kids his only means of escape were sniffing glue and taking drugs. He was going nowhere fast, and he knew it. Perhaps, the film suggests, his bus hijacking was an attempt to stage a televised suicide-by-cop-spectacle in which he would finally be visible to all the people who ordinarily would treat his presence with complete and utter indifference. That would certainly explain some of his bizarre and provocative behaviour. The sad finale to the story is, however, the result of a clumsy police intervention. Had the consequences not been fatal, it would have looked like something right out of Mack Sennett’s Keystone Kop movies.

Roger Ebert was one of a dying breed of film critics who lived, thought and breathed cinema twentyfour-seven. On the poster for the documentary of his life, simply titled Life Itself (2014, Dogwoof) and partly based on Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same title, the tag line following the title is: “The only thing Roger loved more than the movies.” Now, already here the film has lost me, as it soon becomes clear that life and film were inseparable for Ebert. The film itself is a rather lazy affair. However much I appreciate spending two hours at Ebert’s hospital bed, these overlong scenes does not add much to the story. We spend by far too much time looking at the result of the radical surgery on Ebert’s jawbone cancer than gaining an insight into his work.

Roger Ebert was one of a dying breed of film critics who lived, thought and breathed cinema twentyfour-seven. On the poster for the documentary of his life, simply titled Life Itself (2014, Dogwoof) and partly based on Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same title, the tag line following the title is: “The only thing Roger loved more than the movies.” Now, already here the film has lost me, as it soon becomes clear that life and film were inseparable for Ebert. The film itself is a rather lazy affair. However much I appreciate spending two hours at Ebert’s hospital bed, these overlong scenes does not add much to the story. We spend by far too much time looking at the result of the radical surgery on Ebert’s jawbone cancer than gaining an insight into his work.

Sure, there are amusing clips from the Siskel & Ebert show, a few decent interviews with colleagues and friends and some good scenes looking back at his days as a daring editor of a student paper. But we never to the most important issue as many of the best film critics of his generation are either retiring or being sacked: The rise and fall of the intellectual standards in film criticism.

Although he was the only film critic to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the only critic to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, he was by no means the only one who rocketed into stardom as a critic in the 1960s, but the film has very little to say about the social and political context of his work or about important contemporary colleagues such as Pauline Kael or Andrew Sarris. Both became influential both in film criticism and in the new academic discipline of cinema studies.

For those of you who want to get a deeper look into the history of film criticism I therefore recommend Jerry Roberts The Complete History of American Film Criticism (Santa Monica: Santa Monica Press, 2010) and Philip Lopate’s (ed.) anthology American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents Until Now (New York: The Library of America, 2006) for historical overviews. Most, if not all, of Pauline Kael’s and Andrew Sarris’ books are still available. Some may be out of print, but they are available from used book shops. I also recommend BRIAN KELLOW’S RECENTLY PUBLISHED BIOGRAPHY OF PAULINE KAEL.

Stanley Kubrick’s low-budget thriller The Killing (1956, Arrow Academy) is one of those films more memorable for its narrative style, technical achievements and sheer raw power that for the acting performances. All of the characters are tired film noir staples, if not outright caricatures, and the only ones who stand out are the crazed sniper (Timothy Carey) killing the race horse and the Hulk-like wrestler (Kola Kwariani, one of Kubrick’s friends from his chess-hustling days in New York) rumbling with two police officers at the race track – both creating a diversion from the heist. But ultimately it is the work by Kubrick’s direction that has been praised as the film’s main asset, although pulp fiction novelist Jim Thompson’s script (based on ex-crime reporter Lionel White’s novel Clean Break) might be the unsung hero of the film’s much-praised use of a fractured timeline.

A director who stayed true to his pulp fiction and low-budget roots throughout his career is Larry Cohen. While receiving a steady income from his work as a television screenwriter for acclaimed series such as The Fugitive (1964–65) and Columbo (1971–2003) he started making gritty B-movies as a director-screenwriter. The results were some truly original and sometimes outright weird crime and horror films. What they lack in technical skills – especially in the effects department – they make up for in great ideas and solid acting performances. God Told me To (1976, Blue Underground) is among his best films, a strange brew of police procedural, religious drama and horror.

Underrated actor Tony Lo Bianco plays NYPD detective Peter Nicholas, a guilt-ridden Catholic who suddenly faces a string of bizarre killings. They are all committed by seemingly ordinary law-abiding citizens who leave the same message before dying themselves: “God Told Me To!” During his investigation Nicholas stumbles on a divine plan for creating a new human race, one in which he himself plays a central role. Superb cast of co-stars such as Sylvia Sidney, Sandy Dennis, Richard Lynch and Andy Kaufman elevates the story into a truly surreal experience.

Underrated actor Tony Lo Bianco plays NYPD detective Peter Nicholas, a guilt-ridden Catholic who suddenly faces a string of bizarre killings. They are all committed by seemingly ordinary law-abiding citizens who leave the same message before dying themselves: “God Told Me To!” During his investigation Nicholas stumbles on a divine plan for creating a new human race, one in which he himself plays a central role. Superb cast of co-stars such as Sylvia Sidney, Sandy Dennis, Richard Lynch and Andy Kaufman elevates the story into a truly surreal experience.

Sam Raimi could be one of Cohen’s disciples. Living off the profits from his production company Ghost House and some hired-gun-jobs as the director for blockbuster spectacles such as SPIDER-MAN (I-III, 2002–07) he has made a few far more memorable low budget horror and crime films. The Evil Dead series (1981–92) is the most obvious cult favourite, but Darkman (1990), The Gift (2000) and DRAG ME TO HELL (2009) are also solid B-movie fodder with brains.

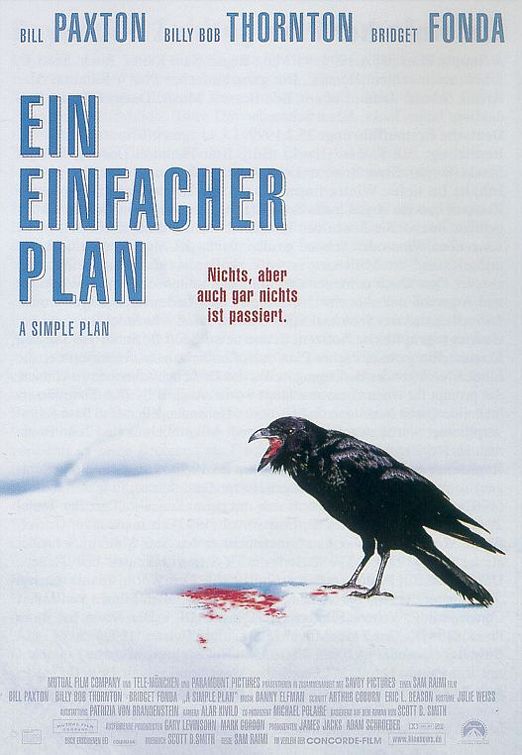

A Simple Plan (1998, Universal), written by Scott B. Smith and based on his novel of the same name, looks like an anomaly in his filmography. It is a small-town crime drama about three working-class men in their thirties finding a crashed private plane full of money in the forest. No-one seems to miss the plane or the money, and they smell a long-last jackpot that can get them out of their hum-drum misery. But the smell of success soon turns foul, and the fortune turns into a TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE. Greed and envy and old conflicts soon ferment into a bloody vendetta with a rather surprising and sad outcome. Bill Paxton plays the family man with responsibilities and Billy Bob Thornton his loser brother, who dreams of buying back the old family farm, once lost by their no-good father to the bank. Not a great movie, but one well-worth a look some rainy afternoon.

A Simple Plan (1998, Universal), written by Scott B. Smith and based on his novel of the same name, looks like an anomaly in his filmography. It is a small-town crime drama about three working-class men in their thirties finding a crashed private plane full of money in the forest. No-one seems to miss the plane or the money, and they smell a long-last jackpot that can get them out of their hum-drum misery. But the smell of success soon turns foul, and the fortune turns into a TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE. Greed and envy and old conflicts soon ferment into a bloody vendetta with a rather surprising and sad outcome. Bill Paxton plays the family man with responsibilities and Billy Bob Thornton his loser brother, who dreams of buying back the old family farm, once lost by their no-good father to the bank. Not a great movie, but one well-worth a look some rainy afternoon.

The same goes for Elaine May’s small-scale gangster film, Mikey & Nicky (1976, Prism Leisure). May was once part of New York’s favourite comedian-duo Nichols and May with future director Mike Nichols. One could easily imagine her becoming the female equivalent of Woody Allen in the film industry. But although she wrote the Oscar nominated scripts Heaven Can Wait (1978) and Prime Colors (1998), her career as a director turned into a disaster. Ishtar (1987) is her most notorious fiasco since it was extremely expensive, but Mikey & Nicky was a small-scale prelude. May spent an enormous amount of film, went way over budget and delayed the release for eighteen months.

The film got the reputation for being a lost treasure when Paramount chose to kill it after just a few days release on a couple of screens in New York. But even though there are a few scenes that captures the charisma of actors-friends John Cassavetes and Peter Falk in the title roles the film never becomes the in-depth character study it pretends to be. Too much dialogue is running on empty, the surprise twist is rather unsurprising and the Cain & Abel drama never packs any emotional punch as the two friends and rivals are, at the most, mildly interesting sleazebags.

The film got the reputation for being a lost treasure when Paramount chose to kill it after just a few days release on a couple of screens in New York. But even though there are a few scenes that captures the charisma of actors-friends John Cassavetes and Peter Falk in the title roles the film never becomes the in-depth character study it pretends to be. Too much dialogue is running on empty, the surprise twist is rather unsurprising and the Cain & Abel drama never packs any emotional punch as the two friends and rivals are, at the most, mildly interesting sleazebags.

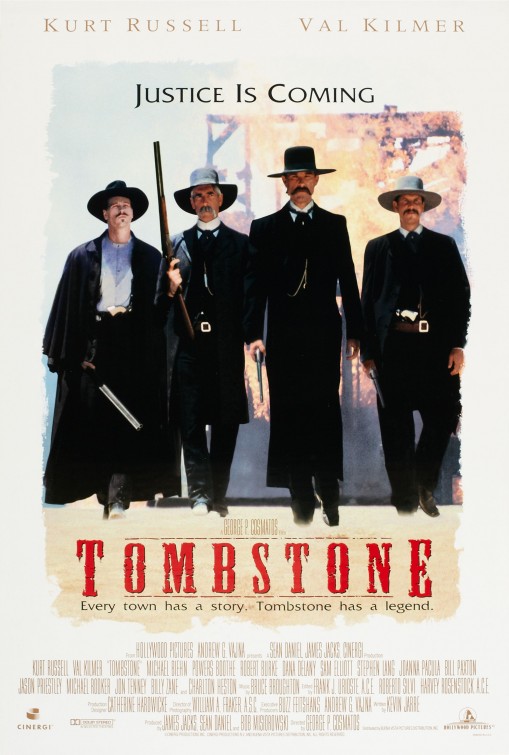

Slightly more interesting sleazebags are to be found in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone (1993, Cinergi), which I prefer to Lawrence Kasdan’s ridiculous whitewashing of the Earp clan in Wyatt Earp (1994). Kurt Russell actually looks like Wyatt, as does Sam Elliott as his brother Virgil, but the main quality in this uneven film is the portrait of the corrupt Wild West town. George P. Cosmatos is officially credited as director, but screenwriter Kevin Jarre (Glory, The Devil’s Own) was originally set to be the director and started the filming only to be fired by star Kurt Russell. After Cosmatos was brought on, Russell claims the director only acted as a hired gun, directing in accordance with the day-to-day shooting script provided by Russell himself.

Regardless of the complicated backstory, the film turned out to as one of the better revisionist Westerns of the 1990s – see also Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) and Mario Van Peebles’ Posse (1993) – one that took a long hard look at the cracks in the legends of the American West. Tombstone is all about money and self-interest even if Virgil at some point has a slight case of bad conscience as a sheriff. It does not last long, as the vendetta with the outlaw bunch known as The Cowboys escalates into a war. Ultimately we get a complicated, though not complex, study of the Earps as the embodiment of 19th century capitalism in the twilight zone between crime and the law: greedy, scheming, ruthless and moral in public appearance only.

Regardless of the complicated backstory, the film turned out to as one of the better revisionist Westerns of the 1990s – see also Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) and Mario Van Peebles’ Posse (1993) – one that took a long hard look at the cracks in the legends of the American West. Tombstone is all about money and self-interest even if Virgil at some point has a slight case of bad conscience as a sheriff. It does not last long, as the vendetta with the outlaw bunch known as The Cowboys escalates into a war. Ultimately we get a complicated, though not complex, study of the Earps as the embodiment of 19th century capitalism in the twilight zone between crime and the law: greedy, scheming, ruthless and moral in public appearance only.

Cecil B. De Mille’s circus epic The Greatest Show on Earth (1952, Paramount) got an Oscar for best picture more than sixty years ago. Today it is often named as one of the worst films ever to have received an Academy Award with its poor acting and old-fashioned melodrama antics, although the blatant sexism is perhaps the film’s most unbearable feature for the audience of today. That Charlton Heston’s cold and sadistic manager is celebrated as the preferable object of female desire in a film made for a family audience gives us a good insight into the ideal masculinity of the 1950s. It is also a sign of De Mille’s reactionary glorification of the male übermensch, which he repeated throughout his long career in the movies, most famously in The Ten Commandments (1956).

Being the De Mille of the double standards – Christian family values, sure, but first a long, hard look at sin and depravity – I rather expected the film, which I had not seen since I was a small kid, to hint at some decadent behaviour among the circus artists. Sure enough, trapeze artist Sebastian (Cornel Wilde), vaguely defined as French or at least from southern Europe, and all of the younger women are in serious heat. Some of the rather blatant sexual innuendos no other director at the time could get past the censorship, particularly when trying to get the film certified for a general audience. The only long-lasting value of this overlong and often off-putting film is the scenes that document of the circus performances and a few glimpses of the lives of the artists in-between the shows.

Scraping the bottom of the barrel in this roundup of assorted titles I came up with Kevin Smith’s Tusk (2014, Lionsgate), a one-note joke that turns out to be unfunny, plain dumb and repulsive. Not that a film about a man who is drugged and turned into a human walrus by a salty dog turned mad scientist is a hopeless idea per se. Just think about the many outlandish plots in today’s cult movie favorites. But at no point in this sad story about a narcissistic, two-timing and obnoxious star of web talk radio who gets his comeuppance does the word ‘entertaining’ even remotely come to mind. The characters are utterly boring, the plot has no interesting twists and there is not one good one-liner – not one – which is a first in a film by Smith. The only category that fits is that of John Waters’ bad bad taste: no flair, merely disgusting.

Scraping the bottom of the barrel in this roundup of assorted titles I came up with Kevin Smith’s Tusk (2014, Lionsgate), a one-note joke that turns out to be unfunny, plain dumb and repulsive. Not that a film about a man who is drugged and turned into a human walrus by a salty dog turned mad scientist is a hopeless idea per se. Just think about the many outlandish plots in today’s cult movie favorites. But at no point in this sad story about a narcissistic, two-timing and obnoxious star of web talk radio who gets his comeuppance does the word ‘entertaining’ even remotely come to mind. The characters are utterly boring, the plot has no interesting twists and there is not one good one-liner – not one – which is a first in a film by Smith. The only category that fits is that of John Waters’ bad bad taste: no flair, merely disgusting.

© Michael Tapper, 2015. Web exclusive 2015-04-11.