Robin  Riley Film, Faith, and Cultural Conflict: The Case of Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ Westport, Connecticut & London: Praeger 2003

Riley Film, Faith, and Cultural Conflict: The Case of Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ Westport, Connecticut & London: Praeger 2003

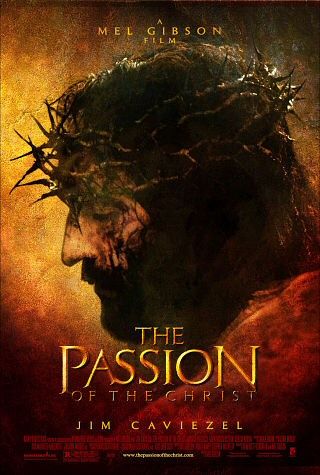

The Passion of the Christ USA 2004 Directed by Mel Gibson Screenplay Benedict Fitzgerald, Mel Gibson Cinematography by Caleb Deschanel Edited by John Wright Art Direction by Francesco Frigeri Music by John Debney With Jim Caviezel Jesus Monica Bellucci Mary Magdalene Maïa Morgenstern Mary Rosalinda Celentano Satan Luca Lionelli Judas Iscariot Mattia Sbragia Caiaphas Hristo Naumov Shopov Pontius Pilate Claudia Gerini Claudia Procles, wife of Pilate Francesco De Vito Peter Produced by Mel Gibson, Bruce Davey, Stephen McEveety Production Company Icon Productions Runtime 126 minutes.

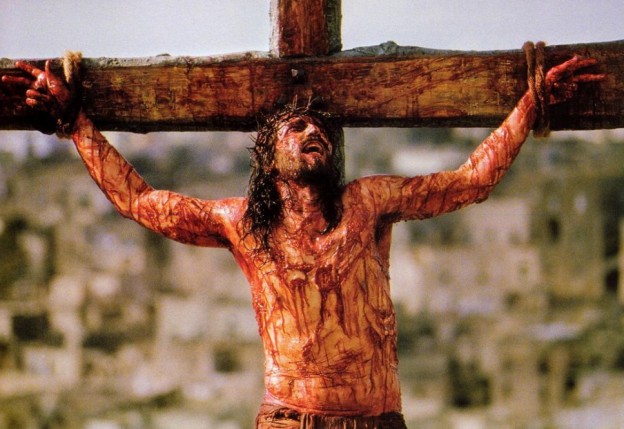

Gethsemane, A.D. 33. Visited by Satan during his prayers, Jesus rejects the temptations and is soon arrested by soldiers led by Judas Iscariot. He is taken to a nightly meeting of the Pharisees, manipulated by High Priest Caiaphas into sentencing Jesus to death. Ignoring a few protesters, Caiaphas then takes Jesus to Roman governor Pontius Pilate in order to formally enforce this decision. Pilate sends Jesus to local puppet ruler King Herod in an attempt to stay out of what he sees as an internal Jewish conflict, but Herod soon sends Jesus back without having passed any sentence on him, failing to find anything threatening or criminal in his activities. Following his own tradition of releasing a prisoner every Passover, Pilate offers the gathering crowd in Jerusalem the choice between well-known murderer Barabbas and Jesus. Again, Caiaphas manipulates to have the crowd shout for Jesus to be crucified, and therefore Barabbas is released. Hoping to satisfy the anger of the priests and their followers, Pilate orders Jesus to be flogged. The Roman soldiers starts with canes and then proceeds with scourges designed with metallic hooks to rip the flesh of the flogged. Jesus is nearly beaten to death in front of the priests, only the intervention of an officer, acting on Pilate’s command, saves his life. When the bleeding Jesus, wearing a crown of thorns pressed onto his head by the Roman soldiers, is paraded yet again in front of the crowd, Pilate finds that Caiaphas and his mob still insist on crucifixion. Washing his hands of this final death-sentence, Pilate orders his soldiers to comply. During Jesus’ struggle to carry his cross to Golgate, aided by disgusted on-looker Simon of Cyrene, Judas hangs himself. On the cross between two robbers, Jesus promises salvation to the repentant one, while the other, who violently mocks Jesus, gets his eyes plucked out by a raven. In front of his crying mother Mary, Mary Magdalene, and some Roman soldiers – several of them gambling and drinking at the foot of the cross but one or two sensing the divinity of their crucified victim – Jesus prays for the forgiveness of his persecutors. At the moment of Jesus’ death, a storm scares Caiaphas away from Golgate. When he comes back to the temple, it is ripped in two by an earthquake in front of his eyes. Days later, in the stillness of a beautiful morning, Jesus rises from the dead in his tomb.

It is ironic that the Catholic Church and the Protestant conservatives, who raged against The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) for straying away from the ‘facts’ in the Gospels to the fiction of Nikos Kasantzakis and ‘making a profit’ from the life of Jesus Christ, now lovingly back the marketing of The Passion of the Christ, claiming it to be an earnest and truthful interpretation. The details of Mel Gibson’s take on the story – the arrest of Jesus, his kangaroo court trials by the Pharisee priests, King Herod and Pilate, his flogging, his suffering walk to Golgotha, crucifixion, death and resurrection – are, in fact, largely drawn from mystic/prophet/stigmatist Anne Catherine Emmerich’s (1774-1824) influential, detailed, anti-Semitic ravings The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, about how the ’hard-hearted Jews’ killed the Christ. Furthermore, Gibson’s production company Icon cashes in on an ancillary market for everything from books to jewelry (nine-inch nails in silver, anyone?) previously unheard of in connection with a religious blockbuster.

But then this is a Jesus depicted in accordance with what many conservative church leaders would like to see on the screens. And after being invited to special screenings, where critics and journalists weren’t allowed to enter, they promoted the film not only by using words like those above but by directly ordering their parishes to the cinemas at the premiere. No wonder, since Gibson has redefined Jesus safely in accordance with the most reactionary, patriarchal traditions of the Catholic and the Protestant church. Also, he has reinvented Jesus Christ as a Spiritual Superman for a right-wing high concept marketing, cleaning up the Passion narrative of anything that could come off as liberal, humanistic or philosophically complex. Instead, we get a prolonged and detailed account of the main character’s suffering and death in a ritualistic macho stoicism strikingly similar to the 1980s Stallone, Chuck Norris, Van Damme etc. fare, where spectacular beatings and tortures beyond what a normal person can take merely toughens up the leading action-man before kick-ass time. Gibson should know. He has starred in a few himself: Lethal Weapon (1987), Payback (1999) et.al.

then this is a Jesus depicted in accordance with what many conservative church leaders would like to see on the screens. And after being invited to special screenings, where critics and journalists weren’t allowed to enter, they promoted the film not only by using words like those above but by directly ordering their parishes to the cinemas at the premiere. No wonder, since Gibson has redefined Jesus safely in accordance with the most reactionary, patriarchal traditions of the Catholic and the Protestant church. Also, he has reinvented Jesus Christ as a Spiritual Superman for a right-wing high concept marketing, cleaning up the Passion narrative of anything that could come off as liberal, humanistic or philosophically complex. Instead, we get a prolonged and detailed account of the main character’s suffering and death in a ritualistic macho stoicism strikingly similar to the 1980s Stallone, Chuck Norris, Van Damme etc. fare, where spectacular beatings and tortures beyond what a normal person can take merely toughens up the leading action-man before kick-ass time. Gibson should know. He has starred in a few himself: Lethal Weapon (1987), Payback (1999) et.al.

Critic A.O. Scott suggested in his New York Times review of the film that Gibson might have taken the cue to his prolonged crucifixion from an episode in The Simpsons. There Homer insists that Mel (who is an animated ‘guest star’) should end his fictitious remake of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) by replacing James Stewart’s speech on tolerance and understanding with a righteous gunfire that ends in a massive body count in the Congress. Adjusting it to the matrix from the typical Ramboistic abuse-and-revenge macho film (a male variation of the rape-and-revenge cycle well worth an in-depth study of its own), I would rather place the ‘revenge’ part in the possible sequel to The Passion.

Picking up from the ending of the first film, we again see the miraculously healed body of Jesus (save for the stigmata wounds after the nails, since they are so essential to Catholic mysticism) rise up from the dead. But now he proceeds to then rips away the stone covering his grave and let the Romans and Pharisees have it. Working title: Christ Part II: The Revenge, marketed with taglines like “The Day HE came back” (with the third day after crucifixion standing in for Halloween) or “Now He’s back and He’s mad as Hell.” In poor taste? Well, just go the Icon web pages of the Passion merchandise, have a look at the standards of taste there and a sequel suddenly doesn’t seem all that unlikely.

Faced with the wrath from a Catholic Legion of Decency, strengthened in their moral righteousness by the Arbuckle and other Hollywood scandals, De Mille made Jesus a sculpture-like icon, an almost immovable, literally radiant other-worldly object in line with traditional Passion plays such as the one in Oberammergau (admired by Hitler for its sentimentality and overt anti-Semitism). Other filmmakers have refrained from showing Jesus, leaving him outside the frame to be stared at in awe by main characters or masses, as in the two versions of Ben-Hur (1926 and 1959), or altogether physically absent but spiritually omnipresent, as in Sign of the Cross (1932) or The Robe (1953).

It was first in the post-Production Code Hollywood 1970s that more daring representations of the Christ and the Gospels could be produced without being targeted by organized attacks from the religious right-wing: Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Godspell (1973) et. al. One of the few that provoked protest was Franco Zeffirelli’s TV production Jesus of Nazareth (1977). After being supported by international directors, Zeffirelli’s film became quite successful, running for many years every Easter on many European TV channels. What a depressing irony it was, however, that the very same Zeffirelli later tried to stop the Venice film festival’s screening of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, condemning the film as sacrilege. By then, the conservative religious extremists had reorganized and gained new power under the supportive Presidency of Ronald Reagan.

With his bland Aryan face not unlike H.B. Warner’s Christ in Cecil B. De Mille’s seminal King of Kings (1927) but without the benevolent smile, his strikingly handsome features (including golden eye lenses to really stress his divine status for Slow Joe in the back row), total faith in his divine status and calling during the confrontations with both Satan’s temptations and the suffering torture of the flesh, Jim Caviezel’s interpretation of Jesus in The Passion of the Christ is designed as the ultimate backlash to the human, soul-searching, doubting and spiritually tormented existentialist of Willem Dafoe’s Messiah of The Last Temptation of Christ. Traditionally, the part about Jesus’ human side has been one of the most sensitive part of his representation in film history. Charles Lyons sketches the background to the Last Temptation of Christ controversy in his book The New Censors (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997): According to many conservative Protestants and Catholics, the Son of Man must never be seen as human in the full sense (This despite the fact that various meetings of church leaders since 432 A.D. have stated how Christ should be seen as being both fully human and fully divine.).

Sure, many the protestors that demonstrated against Scorsese’s film claimed to be offended by the sex scenes, and this angle was not surprisingly highlighted beyond proportion by the media. But reading the articles and speeches referred to in Lyons’ book, the real wrath against this production – made with what the protestors claimed was ‘Jew ish money’, i.e. a conspiracy to distort the Christian religion – was against Willem Dafoe’s Jesus being a man with very human insecurities, full of spiritual longing but unsure about what they mean and how to deal with them. This is in stark contrast to the Christ Triumphant that conservative Christians champion, a Christ fully aware and certain of his divine nature, calling, and destiny. For them this is a dogma at the heart of their belief, and to even consider this, let alone discuss it, is blasphemy in their eyes. It is to make Jesus and therefore his spiritual message, martyrdom, and church ’weak’. On Oprah Winfrey Show (November 12, 1988) Chuck Colson of the Christian Focus on the Family radio station said that ’the film depicts Christ as a whacked-out, lustful and confused wimp…’

ish money’, i.e. a conspiracy to distort the Christian religion – was against Willem Dafoe’s Jesus being a man with very human insecurities, full of spiritual longing but unsure about what they mean and how to deal with them. This is in stark contrast to the Christ Triumphant that conservative Christians champion, a Christ fully aware and certain of his divine nature, calling, and destiny. For them this is a dogma at the heart of their belief, and to even consider this, let alone discuss it, is blasphemy in their eyes. It is to make Jesus and therefore his spiritual message, martyrdom, and church ’weak’. On Oprah Winfrey Show (November 12, 1988) Chuck Colson of the Christian Focus on the Family radio station said that ’the film depicts Christ as a whacked-out, lustful and confused wimp…’

Now, Gibson’s translation of this into the macho myth mentioned above could, of course, be taken as a heavy-handed literalization and even a gross misunderstanding of what really is a spiritual accomplishment. However, judging by the favorable responses and active endorsement of the film by so many churches, it seems to express a rather widespread notion of the Passion narrative. But The Passion of the Christ goes beyond reclaiming the Christian dogmas of the Christ myth and iconography as prescribed by the most conservative forces Named after the Irish Saint Mel, Gibson was raised within and has – after walking on the wild side of Hollywood for some years – returned to a Catholic sect that rejects the reformation of the Latin Mass, the Second Vatican Council’s decisions, and rejects the Pope as ’ursupator’ together with all his predecessors from 1958 and onwards. Strangely, this didn’t stop Gibson from claiming that the Pope had appreciated and even sanctioned the film as ’truthful’, a statement that was immediately denied by the Vatican to the embarrassment of Icon’s marketing department.

Most notably, this sect does not recognize the Nostre Aetate, a declaration on the relationship with non-Christian religions that recognizes historical crimes against Jews (the pogroms, the Holocaust) and Moslems (the Crusades) and sketches a new respect for other faiths. Fueled by this fact and some inflammatory statements by Hutton Gibson, Mel’s father, the accusations of anti-Semitism has been frequent since the start of this production.

Many film critics has generally trivialized this subtext, failing to remember the Christian conservatives’ rhetoric in the Last Temptation controversy and again failing to see how Gibson, without any subtlety, brings back the classical, anti-Semitic narrative into virtually every scene of the film. Starting with the arrest of Jesus by local forces sent by the Pharisees and taken to a nightly meeting commanded by Caiaphas, whose manipulatory designs, leering faces and exaggerated hook-nose is stressed Jew Süss style by the lighting and camera position, Gibson then extends mob ruler Caiaphas’ role all through the film a s the main perpetrator behind the torture and crucifixion of the Christ. Granted, an androgynous Satan (the dark forces in a queer manifestation) enters from time to time to taunt the Christ, but as the instrument of Evil on Earth the High Priest remains unchallenged throughout the film.

s the main perpetrator behind the torture and crucifixion of the Christ. Granted, an androgynous Satan (the dark forces in a queer manifestation) enters from time to time to taunt the Christ, but as the instrument of Evil on Earth the High Priest remains unchallenged throughout the film.

And it is no accident that Caiaphas – symbolically standing as the unchallenged metonymy for the Jewish religion and culture – is shown to be the main target for God’s wrath: the spectacular F/X storm and earthquake that almost destroys not just the curtain, as in the New Testament, but his very temple at the end of the film. Caiaphas even speaks the controversial line: ’His blood be on us and our children’, originally uttered by the masses according to St. Matthew 27.25 before Pilate and used time and again to incite pogroms on the ‘Christ-killers’. Gibson hinted before the release of the film that the line was to be taken out, after some protests from the Jewish community, but he apparently left it in – although without any subtitles – no doubt to the pleasure of his more openly anti-Semitic father. Wrecking the temple at the very end is a clear signal that the foundation of Jewish religion and culture is now corrupt and has to be replaced by something else, i.e. the Christian church (although it may get a completely different meaning in the Islamic world).

To strike back against his critics, Gibson consistently used a paranoid rhetoric about several of them (most notably Frank Rich of New York Times) as ’rabidly anti-Christian’, quoted by Peter J. Boyer in The New Yorker (September 15, 2003) in claiming that ’There is vehement anti-Christian sentiment out there, and they don’t want it’ and that ’If I included that [the Caiaphas line about “His blood be on us…”], they’d be coming after me at my house, they’d come kill me.’ Who ’they’ were supposed to be he didn’t say, but left it to the imaginati on of his supporters. At the same time, Frank Rich could report that Gibson had threatened to kill him, have his intestines ’on a stick’ and kill his dog, although he later (on Jay Leno Show) forgave (!) Rich and claimed it was ’not personal’.

on of his supporters. At the same time, Frank Rich could report that Gibson had threatened to kill him, have his intestines ’on a stick’ and kill his dog, although he later (on Jay Leno Show) forgave (!) Rich and claimed it was ’not personal’.

Gibson’s side-stepping of the central issue of iconographic representation and staging of the Passion narrative in a theological and historical perspective in favor of a paranoid rhetoric of scapegoating is disturbingly continued in Robin Riley’s book Film, Faith, and Cultural Conflict: The Case of Martin Scorsese’s ’The Last Temptation of Christ’ (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2003). Here, the author depicts the controversy as a war fought in the trenches between the film’s Christian conservative critics and its liberal advocates, each demonizing the other. Without any political contextualization of the debate or analysis of the film itself, the book paints a confused picture about how the liberals were just as bad when they argued for the freedom of speech and artistry as the Christian conservatives were in wanting to censor the film. The author doesn’t seem to be able to make a distinction between religious dogma and liberal tolerance, that the former is a totalitarian standpoint excluding and actively supressing any form of debate on these matters.

The book is also littered with unsupported claims such as: ’…the film blends Christian religion with secular concepts in a merger of religious piety and escapist entertainment. Its significance, in this sense, was that it eliminated differences between two distinct and opposing cultural entities.’ In what way The Last Temptation of the Christ – such an obvious example of low-budget, ambiguously narrated art-cinema without any spectacular F/X or classical Hollywood ending – would ever be considered as ’escapist entertainment’ Riley doesn’t say. The Passion of the Christ – with its classical narrative form, spectacular violence, high-profile F/X effects (even, according to some newspapers, using a robot Jesus on the cross), saturated blockbuster release, high concept marketing, ancillary products – makes for a far better case in that respect.

© Michael Tapper, 2004. Film International, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 64-66.