USA 2005

USA 2005

Directed by Robert Rodriguez, Frank Miller, Quentin Tarantino (guest director) Screenplay Frank Miller, Robert Rodriguez Adaptation Graphic Novels Titles Sin City (1991, later retitled Sin City 1: The Hard Goodbye), Sin City 3: The Big Fat Kill (1996), Sin City 4: That Yellow Bastard (1997), Sin City 6: Booze, Broads, & Bullets (1998) Author Frank Miller Cinematography Robert Rodriguez Edited by Robert Rodriguez Art Direction Jeanette Scott Music John Debney, Graeme Revell, Robert Rodriguez With Mickey Rourke Marv Bruce Willis Hartigan Clive Owen Dwight Rosario Dawson Gail Jessica Alba Nancy Callahan Benicio Del Toro Jackie Boy Elijah Wood Kevin Michael Madsen Bob Nick Stahl Rourke Jr aka Yellow Bastard Michael Clarke Duncan Manute Brittany Murphy Shellie Powers Boothe Senator Rourke Rutger Hauer Cardinal Rourke Josh Harnett The Man Produced by Elizabeth Avellan, Robert Rodriguez, Frank Miller Production Companies Troublemaker Studios, Dimension Films Runtime 124 minutes.

Film noir always speaks of a big city universe where the streets were darker with something more than night. In Frank Millers hyperbolic noir gutter there is finally no grayscale left. Literally as well as metaphorically. And hardly much of a soul. Or mind.

Sin City, album one, opens on a balcony. A Man. A Woman. He’s dressed in a black suit, tie, white shirt. She wears a low-cut crimson gown and lipstick in the same color, shining bright in this otherwise black and white night world. Fade in of soft jazz on the sound track. The woman is trembling. The man offers her a cigarette and his sympathies. She responds. They kiss while the world turns into a white and black negative. A pistol shot. The world turns back into black and white. The woman slumps in the man’s arms, dead. The man embraces her. The smoking gun is still in his hand. Rapid camera crane movement upwards to a birds-eye perspective of the scene. Film title Sin City glows blood red against the monochrome background.

As is the case with the rest of the film, this prologue barely offers anything beyond the barest of narrative bones. No background. No psychology. No social or political context. Only an assembly of image compositions recalling innumerable noir films. Or, cover art for pulp crime novels. Or, softcore sex illustrations to crime stories in men’s magazines. All while going robotically through the motions of a condensed version of the plots from the same innumerable works. This is high concept in its essence. Why bother about the laborious effort of trying to do something original when you can boil down the artistic efforts of others and be hailed as a postmodern genius for doing it?

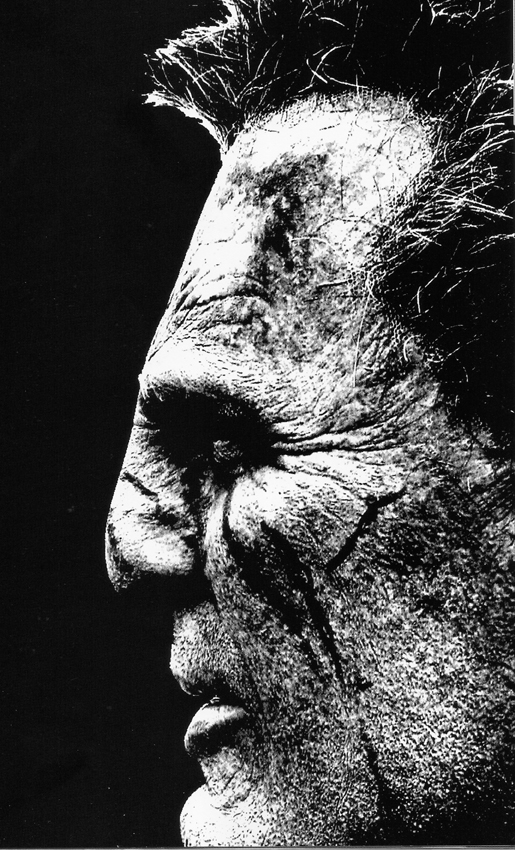

But only nostalgia for the deadly embraces between Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) and Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) and other fatal noir romances don’t sell tickets. Ultra violence in retro clothing does. Enter Marv, Hartigan, and Dwight. They have graduated from Dirty Harry’s Death Wish School of Vigilantism. In tough ”Clint”-poses with nasty handguns they relish more passionately in planning their vengeance than they ever did enjoying that other pleasure in this well of sin: sex.

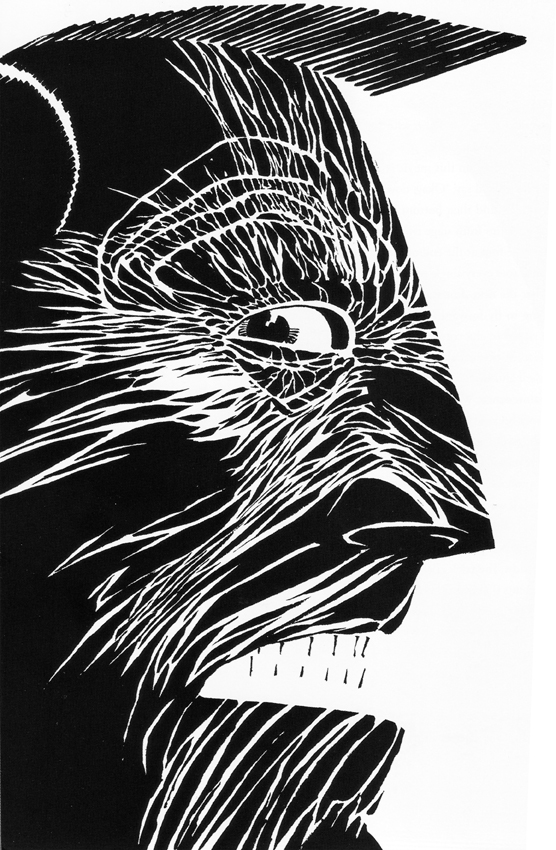

Marv from The Hard Goodbye is maybe the most articulate in this. After waking up beside a prostitute with a heart of gold – Goldie (Jamie King) – that has just given him a free ride and then been murdered in the night without him noticing, he contemplates torturing the perpetrator with the eloquence of a wine-taster’s first sip of a wonderful new bouquet:

It’ll be loud and nasty, my kind of kill. I’ll stare the bastard in the face and laugh as he screams to God, and I’ll laugh harder when he whimpers like a baby… And when his eyes go dead the hell I send him to will seem like heaven after what I’ve done to him. I love you Goldie.

Cut to a series of criminal freaks being systematically shot to be injured but not killed, having their face pressed into filthy unflushed toilet bowls and getting a close shave against concrete being dragged after a car. Marv’s punch line to the movie audience: ”I don’t know about you, but I’m having a ball”. Finally finding the real killer – Kevin, a younger version of nihilist icon Hannibal ”The Cannibal” Lecter – Marv enjoys performing a meticulously slow dismemberment while keeping him alive before feeding what’s left of his living head and torso to the dogs.

All this is of course meant to be splatter aesthetics and to be taken ironically, nudge, nudge. Irony? What irony?

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film version of Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange, young punk Alex’s hobby is to sadistically assault and rape randomly selected suburbians, even performing an absurd tap-dance to the musical classic ”Singin’ in the Rain” for an encore. When being arrested and sent to prison, the state then proceeds to ”cure” him by an even more refined and humiliating sadism. That is irony in the classical sense of the word, revealing the structural violence and authoritarianism behind the humanistic façade of bourgeois democracy.

Sin City would love the comparison to this daring and controversial film, but has no target for its supposed irony and satire in this completely abstract world without history or real people. There are no visible power structures, only individual bad apples – and even more rotten ones. But so far, I have only been talking about the men.

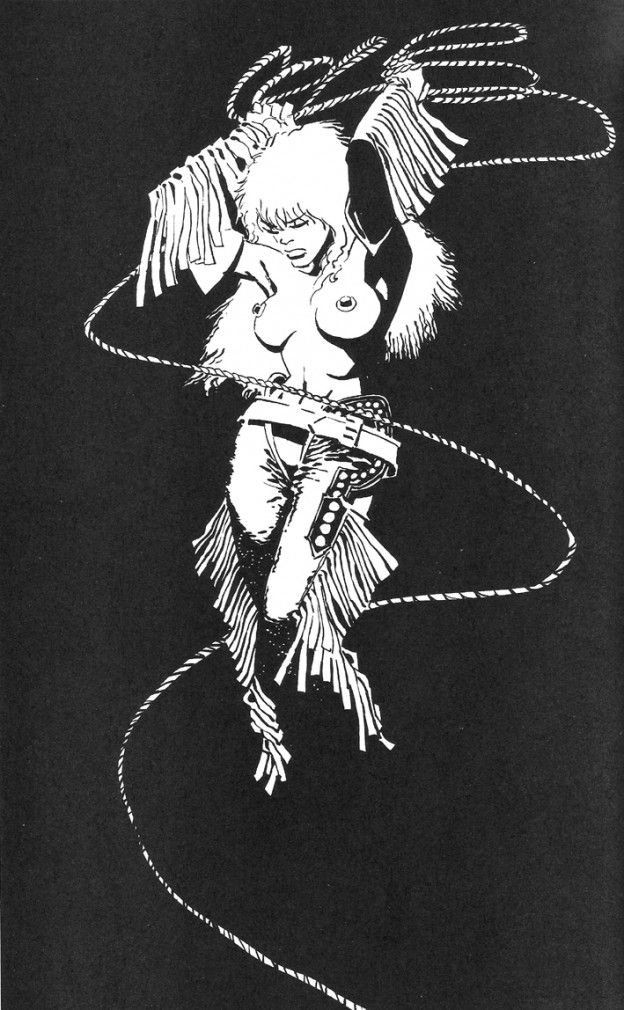

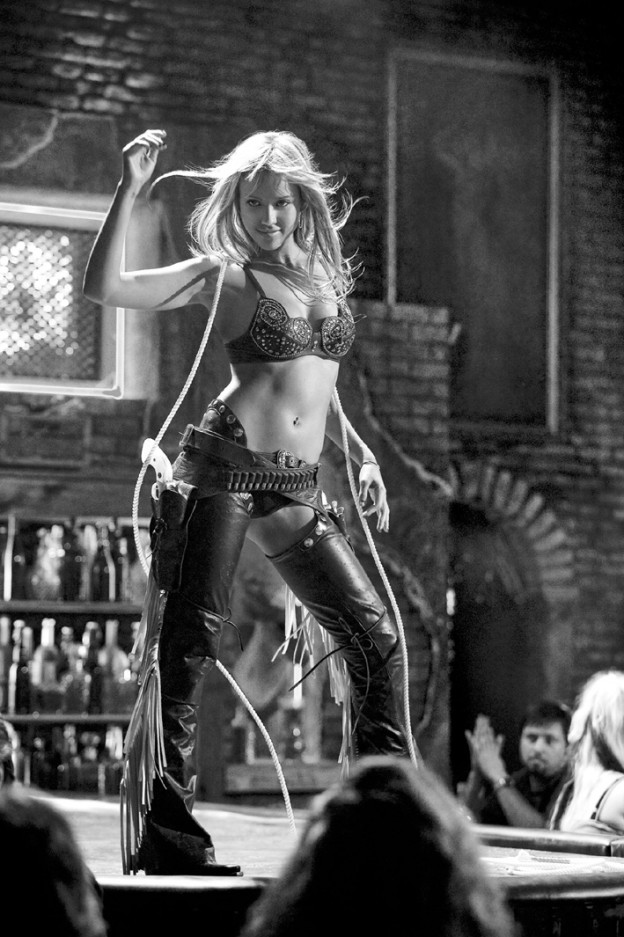

Miller loves to talk in interviews about his femmes fatales having ”girl power”. I assume he meant ”whore power” since almost all the bizarre she-creatures are prostitutes. Now, he hasn’t assembled the heroin skeletons of the socially conscious and realist crime films 1960s and 1970s. Instead, he pigs out among 1980s ghetto-glambabes of the Mad Max-heavy metal-gangstarap-MTV-varitey. He dolls them up in fish-nets, g-strings, leather boots, and a variety of paraphernalia from the kinky department in the porn-store. Sure, there’s Lucille, Marv’s lesbian parole officer. Curiously though, she is one of the few non-prostitutes in Miller’s world and still insists on dressing her gym-perfected hardbody in the same Hustler-lingerie as the sisters of the streets. Ok, they get to kill a few scumbags with samurai swords and swastika-shaped ninja throwing-knives from Tarantino’s Kill Bill storage-room, which makes them – literally – more deadly than the classical femmes fatales. But ”girl power”?

Rather, Sin City’s apocalyptic scenario for this modern-day Sodom – engulfed completely in moral darkness – fits perfectly with the Bush II/Christian right-wing fundamentalist view of today’s secular world. Without God to guide us, mankind simply cannot make any moral judgments or maintain true law and order. Civilization, as we know it, will cease to exist. Sin City will take its place, and its primitive brutality is only matched by its ”indecent” sexuality. The men are all sadistic sex criminals or sadistic brutes in general, the women – whether ”good” or ”bad” – are all hyper-sexualized she-devils.

Finally, the world-as-sewer is revealed here. The only hope for salvation from this abyss is the coming of a rain – courtesy of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver – that will wash all the scum, the whores, the crazies etc. away. In Martin Scorsese & Paul Schrader’s film the – again true – irony is that Bickle’s Puritanism is what makes him a monster more frightening than the villains of the film. Not so here. In Rodriguez & Miller’s Sin City he would be acclaimed as a true-blue hero.

© Michael Tapper, 2005. Film International, no. 16, 2005:4, pp. 58—59.