This interview was made in mid-September 2005 during Lund International Fantastic Film Festival in Sweden. Terry Gilliam arrived the day before to receive a lifetime achievement award at a prize ceremony held in the twelfth century crypt of the town’s cathedral followed by a preview screening of The Brothers Grimm. Tideland was not part of the programme. It would be screened a week later in San Sebastiàn and I had only seen bits and pieces of the film. Consequently, this interview, geared in constant overdrive within a half-an-hour time frame, is mostly about The Brothers Grimm. Then again, as Terry Gilliam is a man with a distinct personal vision, a series of abandoned projects but still on the constant lookout for money in order to continue to make films his way, the interview continuously took off into various directions.

This interview was made in mid-September 2005 during Lund International Fantastic Film Festival in Sweden. Terry Gilliam arrived the day before to receive a lifetime achievement award at a prize ceremony held in the twelfth century crypt of the town’s cathedral followed by a preview screening of The Brothers Grimm. Tideland was not part of the programme. It would be screened a week later in San Sebastiàn and I had only seen bits and pieces of the film. Consequently, this interview, geared in constant overdrive within a half-an-hour time frame, is mostly about The Brothers Grimm. Then again, as Terry Gilliam is a man with a distinct personal vision, a series of abandoned projects but still on the constant lookout for money in order to continue to make films his way, the interview continuously took off into various directions.

Projects, projects…

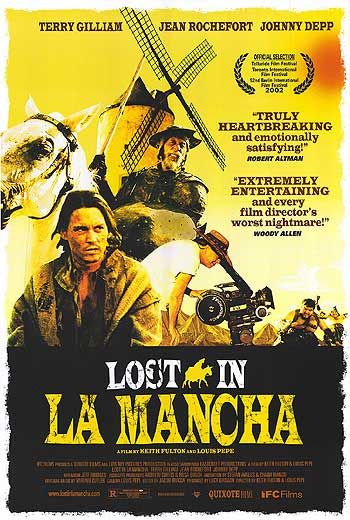

Q: Lost in La Mancha closes with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote being cancelled after just a few days of shooting in late 2000. What has happened with that project since then?

A: Don Quixote has been held up in a legal complication between the Germ an insurance company – who now has the control of all the things from the production – and the French production company. And we still haven’t got the script back. When we do get the script back, I will re-read it to see how I will proceed with the project now that some years have passed. The only thing that is certain is that Jean Rochefort will not play Don Quixote. He simply cannot sit on a horse anymore, and I haven’t seriously thought of anybody else that I want to see in that part.

an insurance company – who now has the control of all the things from the production – and the French production company. And we still haven’t got the script back. When we do get the script back, I will re-read it to see how I will proceed with the project now that some years have passed. The only thing that is certain is that Jean Rochefort will not play Don Quixote. He simply cannot sit on a horse anymore, and I haven’t seriously thought of anybody else that I want to see in that part.

Q: There have been a lot of other projects with your name attached to it. What have you actually been working on after the Don Quixote project?

A: The apocalyptic Good Omens, from the novel by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman, is certainly the one I have worked on the most. We managed to raise $45 million around the world, got Robin Williams and Johnny Depp to come onboard the project and just needed another $15 million from the US … and we couldn’t get it. With those two stars and most of the budget secure, we simply couldn’t get it. That’s how crazy it is in this business! Now that Pirates of the Caribbean has happened and moved Johnny up a few notches as a star, Good Omens might therefore still be possible. We have made all the preparations: designs, found locations … it’s ready to go into production.[1]

There was a project with John Cusack and Dustin Hoffmann attached to it called The Man Who Robbed The Pierre,but that that didn’t happen …[2] Anything for Billy, based on the novel of same title about Billy the Kid by Larry McMurtry, has been around on-and-off for a while. One I really thought would be made at the time was The Defective Detective, about a middle-aged cop that has a mental breakdown and goes into this child fantasy world. I had a screenplay written by Richard LaGravenese, and I was sure that after 12 Monkeys it was to be made at Paramount with Nicolas Cage in the leading role. And there have been many other scripts and ideas bouncing around.

The Brothers Grimm … well, mainly

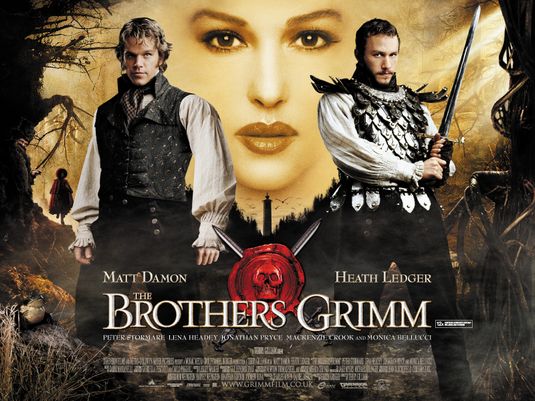

Q: The Brothers Grimm seems to have happened rather suddenly and with you as a director for hire. What is the background of this film?

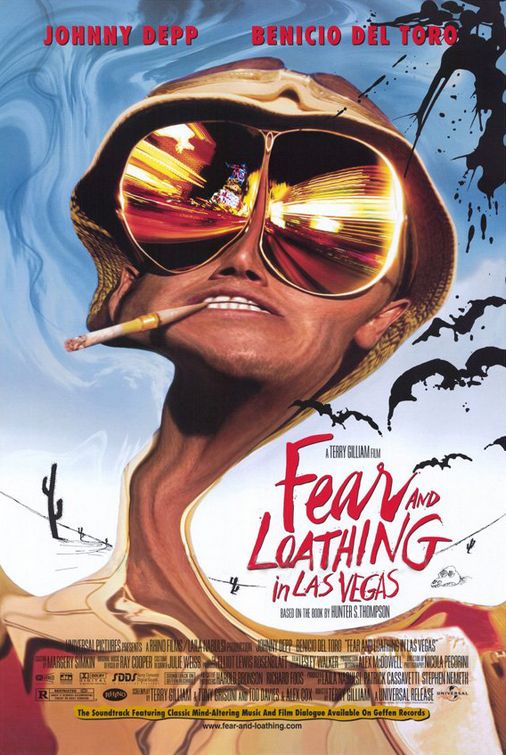

A: I have had a long history of projects either being cancelled after much work or suddenly thrown at me with just a short time of preparation. I remember that Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas was a script that pursued me for years and I said no to it several times. Then, finally, the project got into production with Alex Cox as the writer-director and with Johnny Depp and Benicio Del Toro in the leading roles but Cox got fired very early on in production.

I was asked – again – and said yes, because I wanted to work with Johnny Depp. I wrote a completely new script based on the book and found that it suited me perfectly since it captured so many of my own feelings about America. Therefore, it was an easy thing to adapt. May main concern on that film was not to impress the audience but to make Hunter happy, to honour this book that has had a huge influence on me and my generation. So, Johnny and I lived in constant fear of what Hunter would think, especially since he had big gun. For months he found excuses for not seeing it and kept our dread alive. Finally, he saw it and – thank god – loved it. I am sorry to say that it didn’t find its proper audience in the movie theatres, although it put Hunter’s book back on the top ten list. But since then the film has succeeded to build a solid underground reputation, particularly after the Criterion DVD came out.

Q: And The Brothers Grimm?

A: In the case of The Brothers Grimm Charles Roven, the producer of 12 Monkeys, pursued me with this script[3] he had and that the studio[4] wanted to make. I kept saying no because I didn’t like the script and I was involved with other projects at the time. Eventually I agreed to do it because getting films made is really difficult, and sometimes the studio wants to make a film that you perhaps don’t like initially but think that you can make something of. Tony Grisoni and I rewrote the script on a premise in the original that I liked, which was that these two con-men were using their knowledge of local folk-lore to cheat people and then finally end up with a real challenge in the Enchanted Forest.

Then, when it was time to do the credits for the film, we got in conflict with the Writers Guild of America. It is a long and ugly story I don’t want to get into. In the end we didn’t get scree nplay credit. But if you look in the credits for Dress Pattern Makers, there we are! For the first time in history a film has been made from, not from a screenplay but from a dress pattern. This is the future of film-making! Tony and I made the whole fairy tale world of the film, the officers, the dreamers – and we saw this world as something waiting to be discovered by the Grimm brothers. And we made the whole set-up and dialogue much more funny, which the original script wasn’t.

nplay credit. But if you look in the credits for Dress Pattern Makers, there we are! For the first time in history a film has been made from, not from a screenplay but from a dress pattern. This is the future of film-making! Tony and I made the whole fairy tale world of the film, the officers, the dreamers – and we saw this world as something waiting to be discovered by the Grimm brothers. And we made the whole set-up and dialogue much more funny, which the original script wasn’t.

The important thing was that our rewrite kept us going when we happily went to Prague to make the film. Then, at the very last moment before shooting, the studio pulled out. Crash! Burn! Luckily, within 24 hours Dimension Films were committed to the project. We were rescued again and could go ahead with making the film.[5]

Q: Why Prague?

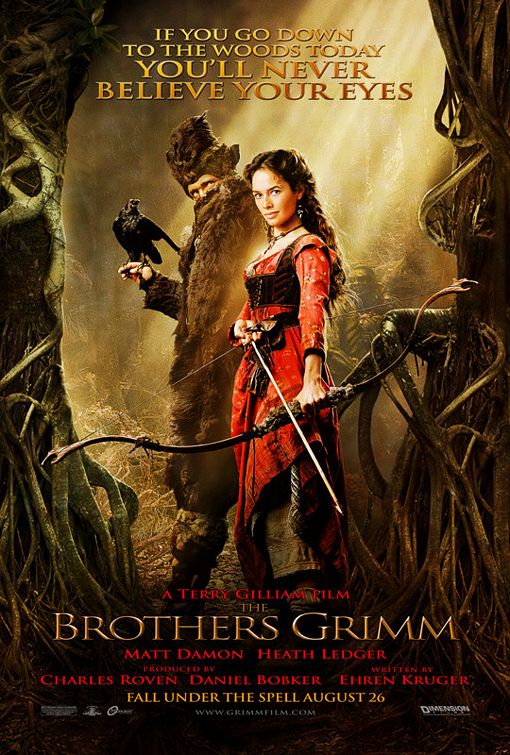

A: It is a place less expensive than, say, North America or Western Europe. But there is also something magic about Prague, and this was a chance to work and live there for seven months. And Bergdorf is a great studio, thanks to the Third Reich that built it for us [laughs]. Prague is also perfect for The Brothers Grimm in the same way that Rome was a perfect place to film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. The local atmosphere and way of thinking perfectly matches the film. Prague has this great history of alchemy and mysticism, and it seems to be haunted by its past. The Czech crew was great, especially when it came to working with traditional material like stone and wood in order to create a believable world of the old villages and the enchanted forest. All the Czech extras, with their wonderful faces, added also added a quality that made the world founded in a convincing reality although it ended up in a fantastic fairy tale landscape.

Q: When did you become fascinated with the classical fairy tales?

A: As all children of my generation, I grew up in a world without television – a staggering thought today – but we have books. I believe that the fairy tales were the first thing I read. And they stuck with me. In fact, every film I have made has in some strange way been a fairy tale. Even the projects that didn’t look like fairy tales from the start, I bent and shaped into a kind of fairy tale. For instance, The Fisher King was written like a contemporary New York story, but since the character of Parry [Robin Williams] believes in a Parsifal knight looking for the Holy Grail and dragons and castles, we turned the city into a magical place for him. In film, I have always been fascinated by Fritz Lang’s silent epic Siegfried, with its huge forest and the hero on a white horse.[6] And it had the quality of the original tales that I think is lost in, for instance, lighter and cleverer versions of the stories like the ones written down by French author Charles Perrault. The Germanic versions are more on the gut-level that attracts me for some reason. Perhaps it has to do with my upbringing in Minneapolis among Swedes and Germans and Nordic and Icelandic tales – maybe you are to blame for all of this!

Q: There have been rumours about much re-writing during the shooting of The Brothers Grimm. If so, what did you change?

A: I usually don’t rewrite during shooting. Once I started filming The Fisher King I left the screenplay alone. The Brothers Grimm was different. I didn’t like the script to start with but thought it had some good ideas that Tony Grisoni and I could work on. Since we were pressed for time, trying to honour a schedule that had already been decided in the midst of changing companies, we sat down every day after shooting and wrote for the next day. Also of importance is the fact that we had an original budget based on the original script. Dimension Films then rejected the budget, and that made me decide on cutting out material that I didn’t want anyway. It had a lot of scenes reminding me of The Mummy remake some years ago with thousands of French troops facing an army of strange creatures coming out of the woods. Things like that.

I really wanted to make the film smaller in scale because I didn’t want it to compete with these films. And I didn’t have the money to do it. So, I broke it down to a version closer to the classical illustrations of the fairy tale books – illustrations portraying a more intimate and in some ways claustrophobic world

Q: Do you usually have specific actors in mind when writing a script? Did you have any particularly on mind for The Brothers Grimm?

A: Normally, I do not have any specific actor in mind when I write a screenplay. In the rewrite and changes of Grimm – as in the working process of any film – things change. At f irst, I had planned for Johnny Depp to take the part of Will. Heath Ledger would have the part of younger brother Jake. Then Johnny decided not to come to Prague, so I switched Heath to the part of Will. Then I meet Matt Damon, and I thought he could play Jake. We did a long dance around the parts that ended up with Matt playing Will and Heath playing Jake. This whole process helped bringing out the characters of the script. I am not sure I made any specific changes because of the switches, but the film changed and got better because of it.

irst, I had planned for Johnny Depp to take the part of Will. Heath Ledger would have the part of younger brother Jake. Then Johnny decided not to come to Prague, so I switched Heath to the part of Will. Then I meet Matt Damon, and I thought he could play Jake. We did a long dance around the parts that ended up with Matt playing Will and Heath playing Jake. This whole process helped bringing out the characters of the script. I am not sure I made any specific changes because of the switches, but the film changed and got better because of it.

Q: Why Peter Stormare?

A: How could I not use him! Besides being a great entertainer on the set during this long and often difficult shooting, he was a hilarious scene-stealer. No shame at all! Sometimes people get annoyed with actors that are bold enough to be as big and overacting and outrageous as he was in The Brothers Grimm, but that’s what I like. There’s a scene where Jake tries to kiss Angelika [Lena Heady] and every time Cavaldi [Peter Stormare] stops him at the very last second. Finally, Jake and Angelika descend into the ground and camera with them. And even then Cavaldi presses his face into every inch of the frame possible before he has to let go. That’s the wonder about shooting: meeting real people and objects, the constant obstacles and surprises they bring to the film.

Realism and hyperrealism

Q: In Lost in La Mancha we see you prepare for the film by drawing what looks like storyboards and designs for sets and costumes. Is that something you have done for all of your films?

A: I am always sketching things – ideas – while going through books, paintings, and illustrations I can steal from [laughs]. In the beginning of my career I storyboarded everything. Now I do it less and less. Instead, I rely more on collaborating with the actors to develop the characters. In designing the films, I work closely with the production designer. In the case of The Brothers Grimm, I had Guy Dyas, who draws much faster and better than me. Then I scribble a little note here a little note there with suggestions for changes. It’s a much faster and more effective way to work.

Q: Starting out as a cartoonist, do you still feel influenced by cartoons?

A: My work is not naturalistic in any way, it’s more like cartoons. Distorted. Hyperreal. I don’t think I can ever see the world in a banal way. I am always inventing stuff to highlight reality.

Q: Coming from a generation of artists – especially film artists – born in the 1940s and starting your career in the 1960s, you must have been confronted with the radical political movements of the time and the heated aesthetic debates about realism, for many in meaning social realism of the Stalinist brand. How has this affected you?

A: For me, the Eisenstein films have always been a source for inspiration. But that is also not social realism; it’s a created world just like mine. I could never just record the surface of everyday life. As an artist I invent more interesting worlds with striking images. They don’t necessarily have to be beautiful, but they have to be strong and meaningful and have something to say. That’s why the design of the films is so important. Every set has to be a character that adds something to the film. Sometimes I can find it easier to do a period film because I can be more inventive. If the film is set in contemporary times, everybody knows what it looks like and that makes me feel trapped.

Q: Have you ever been criticized for your aesthetic choices?

A: All of the time. You name it; I have been criticized for it! In the case of the The Brothers Grimm I got reviews saying that the film is ‘visually overheated’ and has ‘too much imagery’. When I made Brazil hardly anybody talked about the story or the characters, only about the sets and the design of the film. There are so many critics who don’t seem to have any visual sensibility. So, when you do something visually elaborate, they get uncomfortable and usually decide that they don’t like it. They simply don’t understand what it is about. The Hollywood Reporter, I think, said that The Brothers Grimm was visually the ugliest film I had ever made. What do they mean? I think it is beautiful! But there is something there – maybe it’s all the mud, I don’t know – that they cannot grasp. Maybe it has something to do with me shooting the film with wide-angle lenses, which makes the imagery very complex. Much information in every shot, which is exactly what I want. But they just dismiss my work with simple statements like that.

Q: Within your stylized universe you often place people who want to escape their everyday, humdrum worlds and go into new and fantastic dimensions…

A: …and they usually fail to escape! They never quite make it… [laughs]

Q: But I sense ambivalence about this. The fantastic worlds they escape to can be sanctuaries from a grim reality, but these worlds can also be nightmares. In some cases they are both.

A: Oh yes, very much so. And it is not only about escaping; it’s about protagonists seeking out new and other ways of looking at the world beyond banal reality. To have imagination, dreams, and fantasies is essential to survive. It’s about exploring new perceptions. They are doing what I am basically doing every day: making the world more interesting. To be full of surprises. As you get older, it’s harder and harder to be surprised. Television has an irritating way of reinforcing a banal look at the world every day, so it seems to me to be increasingly important to show other possible worlds at the cinema – whatever they might be.

Q: How do you see the relation between the real, everyday world and your fantasy worlds, then?

A: Of course, my fantasy worlds are part of the real world. They are other aspects of it, and I want us to face them rather than reject them. It’s not that I want to leave reality and just go into escapist dreaming. The only one who manages to escape completely is Sam in Brazil, and he ends up going insane. I am looking for a balance. Every film I make therefore represents a way of looking at the world that makes sense to me at the moment. And since I never quite succeed, I am constantly making new efforts.

Q: So, you’re essentially making the same film over and over again?

A: Yes, in this sense I think I do. My wife always says: ‘Same film, different casting’. By that she means the same search for the boundaries between fantasy and reality. The stories are different, but to make them interesting for me, they have to incorporate these elements. I wouldn’t want to make a film about a total fantasy or about everyday life in recorded reality. That would be boring.

Darkness and light and bad parents

Q: Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas is certainly a story about being trapped in a nightmare, and in The Brothers Grimm the protagonists are nearly trapped in their own dark fairy tale landscape. Is your work getting darker?

A: You may be right, and it might have to do with the fact that I am getting older. Eventually, the light switches off and that’s it! [laughs] In Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, I simply wanted to catch the feeling of a novel that is very important for my life and my generation. I keep getting caught in adapting books for films. Maybe what I am secretly doing is trying to get people to read again … by going to the movies?! [laughs] In The Adventures of Baron Munchausen I hoped that people would rediscover the book. That didn’t happen. But in the case of Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, the book actually got back on the bestseller list and was number one for a while. When preparing for The Brothers Grimm, I went back to the original stories. And there are hundreds…

Q: …and only a handful is known.

A: Yes, there were so many that I had forgotten. They first published a book with several hundred stories, and it was a failure. Then they reduced the number of stories in a new edition, and that became a bestseller.

Q: Some bits and pieces and characters from them are used in the film but the already harsh Grimm universe has gotten the most nightmarish treatment in your film.

A: And for a reason. The darkness is what makes the light more beautiful…

Q: …and the struggle to get to the light becomes more meaningful.

A: Absolutely! A problem I see now in the modern world – particularly in America – is the perception of a world without struggle, a world were all our needs are taken care of. To me America is living a comforting dream-lie. As comedy must incorporate elements of tragedy to make it meaningful, life must also have its ups and downs. That is what fairy tales are all about; this struggle to survive the darkness and strive towards light. Now and then nature reminds us about the necessity of struggle, like [the hurricane] Katrina. That’s not all bad.

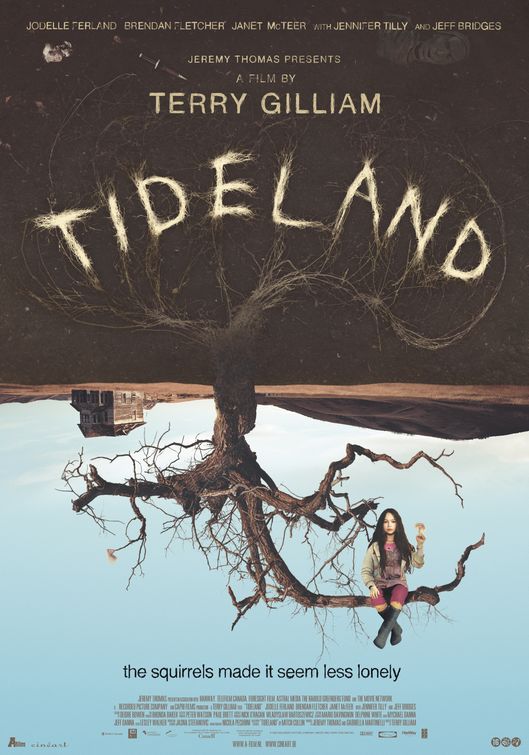

Q: One recurring dark stroke in your films – Time Bandits, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Tideland, for example – is the representation of bad parents. Are they responsible for the state of the world?

A: There are certainly enough of them, and I am one for sure. That’s why I have my son play the stable boy and my daughter work for me as my assistant. In a way this arrangement is a small compensation for me not being around them much when they were young. Now, when they are adults, I keep them close.

It’s not only that, of course, but bad parents tend to be a recurring theme in many classical stories. In Hansel and Gretel, the parents cannot afford to keep their children, and so they put them out in the forest to starve and die. In Cinderella, the mother dies and the father remarries and the girl gets this awful stepmother. These are stories that have been around for a long time and for a reason – because they are about deep psychological problems and how to deal with them. They certainly frighten children but also deal with important issues that have to be confronted.

Tideland, which I wrote after a book sent to me by author Mitch Cullin, has really bad, bad, bad parents [Sally Crooks, Jeff Bridges, Jennifer Tilly]. In a way it’s my Psycho, my disturbing little low-budget film made in-between the monster-productions that I have found have a much more profound effect on people than the films made with bigger budgets. And much of it has to do with the portrait of a child trying to survive bad parents.

Today, all children stories seem to be influenced by Sesame Street, where everything is happy, beautiful and carefree all the time. For me, this is an idealized and all-wonderful, never-ending childhood constructed by adults who are absolutely terrified with the idea that their kids one day will grow up and leave them. I think these modern stories are completely irresponsible since they do not – as the classical fairy tales did – prepare children for real life. Fairy tales tells you about all the horrible, dangerous things of the world, but also about the beauty and wonder of life. And, most important, they tell you that you can survive all the horrors if you keep yourself together and that you achieve happiness even after going through the most terrible ordeals.

Technology, control and realism (again)

Q: How much have the new visual effects technology helped you in translating your fantasies into films?

A: CGIs [Computer Generated Images] makes it so much easier. You can do almost anything you want. It’s a great asset, and it will help more people make movies since it’s relatively cheap. And it’s the same with digital cameras. If I cannot afford shoot on film, I can always use the cheaper digital technology. You do whatever is necessary to tell the story. That is what – in the end – film technology is all about. We did some computer animation of pieces of the sets and the landscape in The Brothers Grimm, but only as far as we couldn’t do these things with real sets. I prefer when you cannot see the seams between what’s real, what’s physical sets, and what’s computer animation. The end result is by far what’s important here.

It’s not that computer animation is a big issue with me. I am constantly surprised by people that make it into a problem. I mean, it’s just a tool and can be used good or bad. It won’t make the film better or worse, but it can help you make what you want. When people criticize films that are enhanced with computer animation they should really look to the stories rather than the technique by which they are made. MirrorMask is one of those recent films that rely entirely on computer animation. But it also has a wonderful story that will engage you in the film. And together they make for a stunning experience.

But there are, of course, examples of films that are better even though they are made with more simple technology. King Kong of 1933 is much cruder but infinitely better and more charming than the more high-tech 1976 version. Still, I am looking forward to seeing Peter Jackson’s version. Maybe it has to do with realism… Computer games tend to become more and more realistic, and that’s not making them better. Something seems to have been lost because when you go and see, say, a marionette show, you learn to accept that world and let your imagination grow within it. This struggle for realism is taking out the magic element of representation. What I am trying to get at is that realism doesn’t equal what’s believable. Sometimes a strange creature can be much more believable within a story than a realistic one.

Q: Talking about marionettes, in Lost in la Mancha we see you prepare for the film by constructing giant puppets. How did you plan to use them?

A: I got the inspiration from Spanish carnivals and festivals, where people were dressed up in costumes and grotesque masks and they sometimes had these string-puppets, which of course is totally unrealistic but beautiful and magical. The experience was quite hypnotic and stimulating to the part of the brain that doesn’t deal with realism and rationality.

Q: In computer animated cartoons like the ones made at Pixar, the film-makers’ original quest was for increased realism. Then John Lasseter said in an interview that he found this effort uninteresting and ordered the artists to go back to more stylization.

A: Yes, that’s what I am getting at. The Toy Story films are amazing, not because they pretend to be realistic but because they are believable. John Lasseter creates this universe of engaging toys, which all have great personalities. MirrorMask also makes a good case for how to make original use of computer animation as an extension of the characters’ universe. Sin City has some magical qualities in its strange cartoon world, although the characters are far too thinly sketched and the plot is too much like the same old crime story to make the film interesting. The same goes for the Star Wars films and for Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow: great images, but much too thin on plot and characters. And these films’ effort to create a futuristic realism is just killing them. Actors all have to stand in front of huge green screens to be inserted as small pieces of an overall design and a routine plot. When George Lucas says he is even using CGI techniques to change actors’ performances, I think it is getting to be ridiculous. I mean, what is he doing? It’s crazy! That kind of control seems to be more about personal neurosis than to try and make good films.

Q: And you have yourself gone from storyboard control to working intimately with actors and others.

A: Yes, I enjoy collaboration, and I think that arguing with the people I select I get a much better result, a much better film.

Q: Isn’t complete control like in the case of George Lucas the continuation of Hitchcock’s dream about not having to actually shoot a film but rather go from vision directly into people’s heads.

A: Sure, but look what happened in his later career. The early work is really exciting. Then in his later years he got so uninterested in the process of translating his ideas into films that he simply didn’t care about the film-making anymore.

I remember Katherine Helmond told me a story about when she worked on Hitchcock’s last film, Family Plot [1976]. The actors had been out all day in the cold rain while Hitchcock sat in a car all the time. She went up and knocked on his window to ask what he thought of her performance. Zzzzz, the window went down. She asked the question. Zzzzz, the window went up again. And you see this complete lack of interest on his part in the later films.[7]

Q: Has your journey gone in the opposite direction – from storyboarding everything in Jabberwocky to collaborating completely in Grimm and Tideland?

A: Basically yes, but even in the early days I didn’t have complete control. I thought I had, but I hadn’t. When you get – as I did – really good actors and comedians, you get people who will do their own thing. The journey for me has more been one of confidence, a trust in my instincts and in the process of collaboration. The by far most important aspect of making good films is to have the right people to work with.

Some last questions … and yes, also about Monty Python

Q: With DVD there have been a lot of alternative versions and directors cut. But so far there is no Terry Gilliam film that has gotten that treatment. Is there a reason?

A: I don’t do director’s cut. There are five different versions of Brazil out there in the world, and that intrigues me.[8] Two of those versions are my responsibility. I made an original version and an American version with some small changes. For these two versions I actually used two endings – one with clouds coming in over the torture chamber, one without – that are actually both in the script. Other than that, I like the idea of putting deleted scenes on DVD releases, because then the audience can judge for themselves whether they are any good or just plain silly bits that we are all better off without. In The Brothers Grimm I cut out the most expensive scene in the film, and I intend to put that on the DVD.

Q: You seem to interact with your strong fan following, especially the web fanzine Dreams?

A: I don’t have anything to do with it besides being available for Phil whenever he wants to come to set to make an interview. In that way I can be more efficient in keeping the fans and other people interested updated about what I am doing, I can cover more territory. I love the web, so I try to cooperate and keep my eye on the websites – also the Python one – as much as possible to send in updates on projects being launched and films being released.[9]

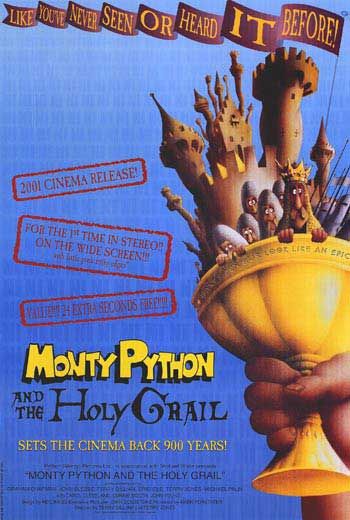

Q: Stage show Spamalot, loosely based mostly on Monty Python and the Holy Grail but also includes other Python material, has been a great success. What did you think about it? Did you have anything to do with it?

A: I really loved to see my animation blown up to huge proportions in 3D. My criticism of the show is that they didn’t have the mud, which I think is essential for the story. Much of the jokes come out of the mixture of this fantastic tale with this awful world of mud and death. On the stage, the jokes tend to come out as less funny for that reason. It will, however, keep Monty Python alive and Eric idle the richest Python on the planet… I didn’t have anything to with it. It’s Eric’s thing altogether. The Pythons collectively decided to hand him the rights, and frankly we were all surprised of the success of the show.

Q: Do you have a hand in the other Monty Python-related industries?

A: Yes. We have a Python office run by one guy, Roger. He manages what we own collectively: The Monty Python Flying Circus show, the films… And so, every day Roger goes out selling whatever he can related to these assets: articulated dolls from Holy Grail and other really stupid stuff that he can think of. I don’t have anything to do with the management or the designs – there are other people doing that – but my wife usually gets as much from the Python shop as possible since it takes care of our Christmas gifts.

Q: Considering the latest boom for animation. Any interest in taking that up again?

A: Well, I don’t think my crude old animation technique could ever compete with what’s being produced today by Pixar or by Hayao Miazaki. Besides, I have grown to like working in dialogue with talented people in various departments of movie-making. Auteurism is such a joke when it comes to film-making, which is a collaborative art. Still, people tend to write about movies – and my movies – in this way.

© Michael Tapper, 2006. Film International, vol. 4, no. 1, 2006, pp.60–69.

Notes

[1] Pirates of the Carribean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003), followed by the forthcoming Pirates of the Carribean: Dead Man’s Chest in 2006.

[2]The Pierre is a luxury hotel in New York.

[3] The original screenplay was written by Ehren Kruger, who got all the screen credits when the film was released.

[4] MGM was the original production company of The Brothers Grimm.

[5] Dimension Films has for a long time been a branch of Miramax. When Bob and Harvey Weinstein left Disney this year, they took Dimension Films with them and decided to let Sony Pictures (formerly Columbia) distribute The Brothers Grimm.

[6] Siegfried is the subtitle of the first part of Die Nibelungen (1924).

[7] American actress Katherine Helmond is mostly known for her starring role in the comedy television series Soap. She has acted in several of Gillliam’s films since Brazil.

[8] See the Criterion box release of Brazil for the details on all the versions.

[9] Phil Stubbs, the editor of web fanzine Dreams.

TV/Filmography

(official list, see interview)

As contributor

Cry of the Banshee (1969) animator

Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-74) actor, animator

And Now for Something Completely Different (1971) Monty Python-compilation film

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1974) actor, animator

Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) actor, animator

Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1982) actor

Monty Pyhon’s The Meaning of Life (1983) actor, animator, co-director

Spies Like Us (1985) cameo

The Hamster Factory and Other Tales of 12 Monkeys (1996) documentary on Gilliam’s work on 12 Monkeys

Lost in la Mancha (2002) documentary on Gilliam’s work in 2000 on the shelved project The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

As director

Jabberwocky (1977) also co-script, animation

Time Bandits (1981) also co-script, animation

Brazil (1985) also co-script

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989) also co-script

The Fisher King (1991)

12 Monkeys (1995)

Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) also co-script

The Brothers Grimm (2005)

Tideland (2005) also co-script

For more details about unmade projects and future plans, visit the web fanzine Dreams (ed. by Phil Stubbs):

www.smart.co.uk/dreams/