United Kingdom/USA 2016. Director Ron Howard Screenplay Mark Monroe, P.G. Morgan Cinematography Michael Wood Editor Paul Crowder Music Ric Markmann, Dan Pinella, Chris Wagner. With John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Ringo Starr (Richard Starkey), Brian Epstein, George Martin, Whoopi Goldberg, Sigourney Weaver, Elvis Costello, Eddie Izzard, Richard Lester. Producers Brian Grazer, Ron Howard, Paul McCartney, Scott Pascucci Companies Imagine Entertainment, White Horse Pictures, OVOW Productions, Universal Music Group for Apple Corps. Length 1.39.

A compilation of archive footage featuring music, interviews, performances and stories of The Beatles' 250 concerts from 1963 to 1966 plus recently recorded interviews with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and a number of others commenting on The Beatles as a cultural phenomenon in the early-to-mid-1960s

The most striking experience in Eight Days a Week – even to seasoned Beatle historians/fans/maniacs – is what a good live act the band was: well-rehearsed, tight, playful and infectiously energetic. Many of their performances, especially on their American tours, were cut short due to the mob hysteria, but even though they teared off 10-15 songs in just 30 minutes, they apparently made a lifelong impression on the assembled crowd. That is certainly affirmed by celebrity interviewees such as Sigourney Weaver and Whoopi Goldberg, two in the crowds of many thousand teenage girls drowning out the music with their incessant screaming. Weaver, who still went by her original first name Susan back then, is actually caught in a camera shot having had her curls ironed out to look like a Beatle “Mophead”.

Goldberg’s memories are, however, more interesting, since they attest to the fact that the group had many African American fans. They did not necessarily regard them as white but as “colorless”, to use Goldberg’s words, that is as outside the Jim Crow segregationist division between “whites” and “coloreds”. Historian Kitty Oliver, who caught them in Jacksonville, elaborates on their importance as a group that transcended social and ethnic barriers by talking about how important it was for her that they took a stand against segregated concerts. By forcing the arrangers to dismiss those plans, the youngsters could get the first taste of a possible new world of equality.

Paul McCartney tried to play down the political controversies by belittling their cultural importance – “we’re not culture, we’re only doing this for fun”, he says in an interview – and this is perhaps symptomatic for the minor divisions in the band that would widen to the final breaking up in 1970. John Lennon the political activist would never write the main theme song to a blatantly racist film like the James Bond instalment Live and Let Die (1973). McCartney the businessman did.

They certainly were not “just entertainment” but politically and culturally important, as is shown by the Bible-belt hate response to Lennon’s comment that they were “more popular than Jesus” to the young generation. The burning of records in Birmingham, Alabama – the place where Martin Luther King had served as a pastor and in 1963 made a symbolic standing for the Civil Rights Movement – is horrifyingly close to the Nazi book burnings. The controversy was just an excuse for the white supremacists of the South to flex their muscles. Four white popstars had set a dangerous precedent by enforcing desegregation, and they were therefore marked as “race traitors”.

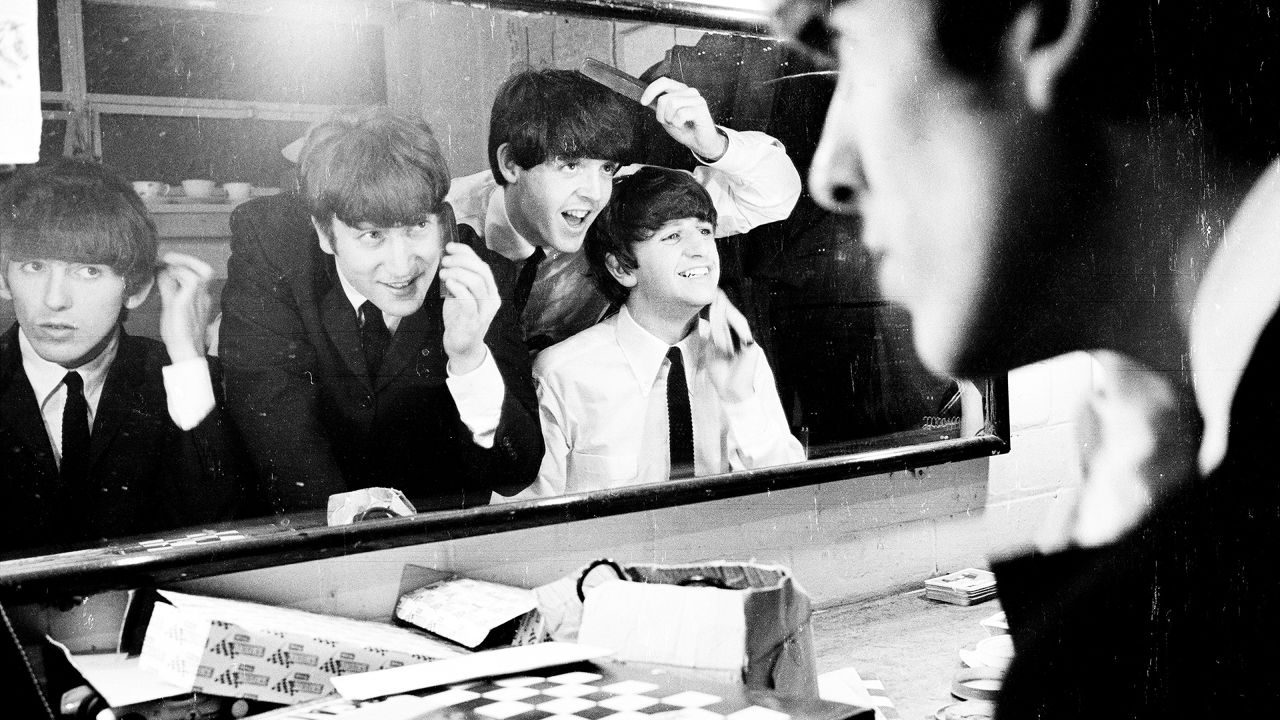

The Beatles were, of course, not all controversy, they were also charming and funny, as the old interviews and behind-the-scenes clips show. A key to their brilliance in handling the media and also to survive fame was their close relationship, acting at times almost like a comic act of four, a British version of the Marx Brothers. Ringo remembers that when he became a member, he felt like he got three brothers. Coming from the same poor working-class background in Liverpool, they learned to look after each other while on tour or playing eight hour sets for scraps in Hamburg’s red light district. Solidarity made them into one tight unit, which is both touching and hilariously visible in several of the scenes in which they riffing on jokes together and finishing each other’s lines in super speed.

There is a wonderful moment when they arrive for the first time in America and the first – utterly ridiculous – question is: “What about the reports that you guys are nothing but a British Elvis Presley?”, to which they instantly reply “It’s not true!” while making Elvis postures. But they could also strike out on their own. In one clip, John takes the piss out of an American interviewer who apparently know nothing of the band and their music by pretending to be named Eric while leading the conversation astray by constantly misunderstanding everything he says. But there is never any sense of malicious “irony”, just good-natured playfulness.

The success of The Beatles once again proves that nothing compares to the genuine article. Far from being a media-savvy or media-trained they were four guys who truly loved writing and performing songs, and it is tangible. Success did not kill The Beatles; it was mainly Capitol Records’ shitty contract that did the job. Making preciously little on their recordings, they were forced to go on long tours – essentially the three-year period of 1963–66 was one long tour – to earn any money. At the same time, they had to write new songs since they were obligated to release a single every three months and an album every six months.

And so they ended up in big arenas with bad sound systems and wall of policemen between them and their fans. For their 1965 concert at Shea Stadium, New York, Vox built special 100 Watt speakers for them; today’s sound systems for major rock bands are about 300 000 Watt. Nobody could hear them for all the screaming, and even they themselves could not hear anything despite standing as close together as they could. Ringo claims that he had to look at the other band members’ ass-shaking to keep the drums in sync.

In the little spare time they had, they did photo sessions, films, commercials and were sent to various social occasions. Essentially, they became a brand, not a band. What was once the real deal of inspiring working-class rebellion and creativity soon turned into a machine for making phony products for the middle class. It is no coincidence that their fourth album was named Beatles for Sale. Finally, they escaped into the Abbey Road studio that from the start had documented them in their prime power. Up until Rubber Soul, their albums were recorded live in the studio, i.e. they played together as they did on stage.

Exhausted from their years on the road and dead tired of their image, they began an experiment to departure from their initial “cute period”, as they called it. Rubber Soul was, in Ringo’s words, “the departure”, and their controversial cover of their American compilation album Yesterday and Today (1966), on which they posed grinning in lab coats covered with blood, raw meat and mutilated baby dolls, was one big “fuck you”-gesture to the past. At last they found a new sound and a new alter ego in the album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. They had become something more than just four lovable Mopheads.

© Michael Tapper, 2016. Web exclusive: michaeltapper.se 2016-09-16.