Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and Other Newly Restored Works

USSR 1924–34

Films: The Man with the Movie Camera (Chelovek s kinoapparatom, 1924; 1.08), Kino-Eye (Kinoglaz, 1924; 1.18), Kino-Pravda No. 21 (1925, 0.23), Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (Enthusiasm – Simfoniya Donbassa, 1931; 1.06), Three Songs of Lenin (Tri pesni o Lenin, 1934; 0.59).

Bluray: USA 2015. Flicker Alley, Lobster Films & Blackhawk Films Collection with the support of Eye, CNC, Roam & La Cinématheque Toulouse.

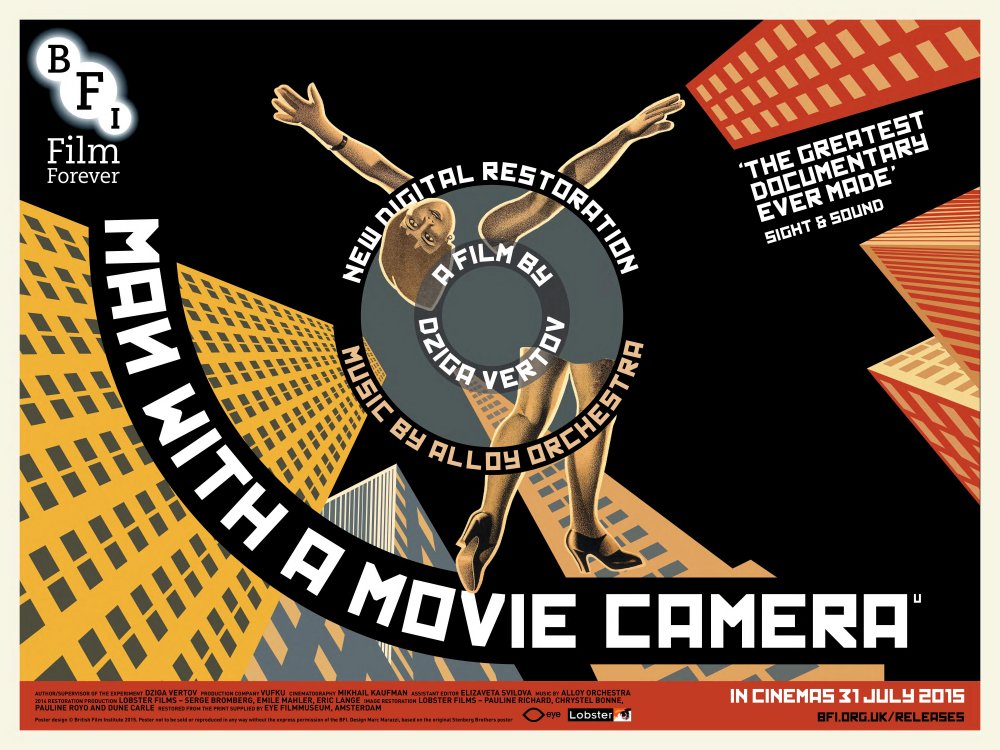

Man with a Movie Camera

USSR 1929

Films: The Man with the Movie Camera (Chelovek s kinoapparatom, 1924; 1.08), Kino-Pravda No. 21 (1925, 0.36), Three Songs of Lenin (Tri pesni o Lenin, 1934; 1.01), David Collard on Three Songs of Lenin and W.H.Auden (2009; 0.07), Simon Callow reads W.H. Auden’s Versus from Three Songs of Lenin (2009; 0.03).

Extras: Audio commentary by Yuri Tsivian. New film score by Michael Nyman and played by his band. New soundtrack for Kino Pravda No. 21 and Three Songs of Lenin by Mordant Music

Bluray: United Kingdom 2015. British Film Institute.

This new compilation of films by Denis Kaufman, a.k.a. Dziga Vertov (‘Spinning Top’), follows in the footsteps of DVD collection LANDMARKS OF EARLY SOVIET FILM, containing Vertov’s 1926 film Stride, Soviet! Besides presenting a new digital transfer of the director’s most famous film – one of the most influential title in the history of experimental as well as documentary filmmaking – the US edition includes four and the UK edition two of his other works (listed above) typical of the type of the agitprop films he made in the 1920s and early 30s.

This new compilation of films by Denis Kaufman, a.k.a. Dziga Vertov (‘Spinning Top’), follows in the footsteps of DVD collection LANDMARKS OF EARLY SOVIET FILM, containing Vertov’s 1926 film Stride, Soviet! Besides presenting a new digital transfer of the director’s most famous film – one of the most influential title in the history of experimental as well as documentary filmmaking – the US edition includes four and the UK edition two of his other works (listed above) typical of the type of the agitprop films he made in the 1920s and early 30s.

By the mid-thirties Joseph Stalin had won the power struggle in Kremlin and dictated socialist realism as the aesthetic ideal for the arts. Vertov abandoned his experimental style and conformed to the party line. He broke off with his brother Mikhail, the cinematographer featured in Man with a Movie Camera, due to artistic differences. They never worked together again. Their younger brother Boris Kaufman had moved with their parents to Poland and then to Paris. He would also become a prominent cinematographer, although in Hollywood. His American feature film debut was none other than On the Waterfront (1954), for which he got an Academy Award.

The films compiled in the US and the UK editions represents the brief period of intellectual enthusiasm and artistic freedom that followed the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. New frontiers of all aspects of life were to be explored in order to make a conscious break with the past, and in art no frontier seemed more promising than cinema – a new and vital art form unburdened by aristocratic or bourgeois traditions. Lenin declared it as the most important art form in the struggle to win the masses, and a new generation of filmmakers set out to make revolutionary films for revolutionary people.

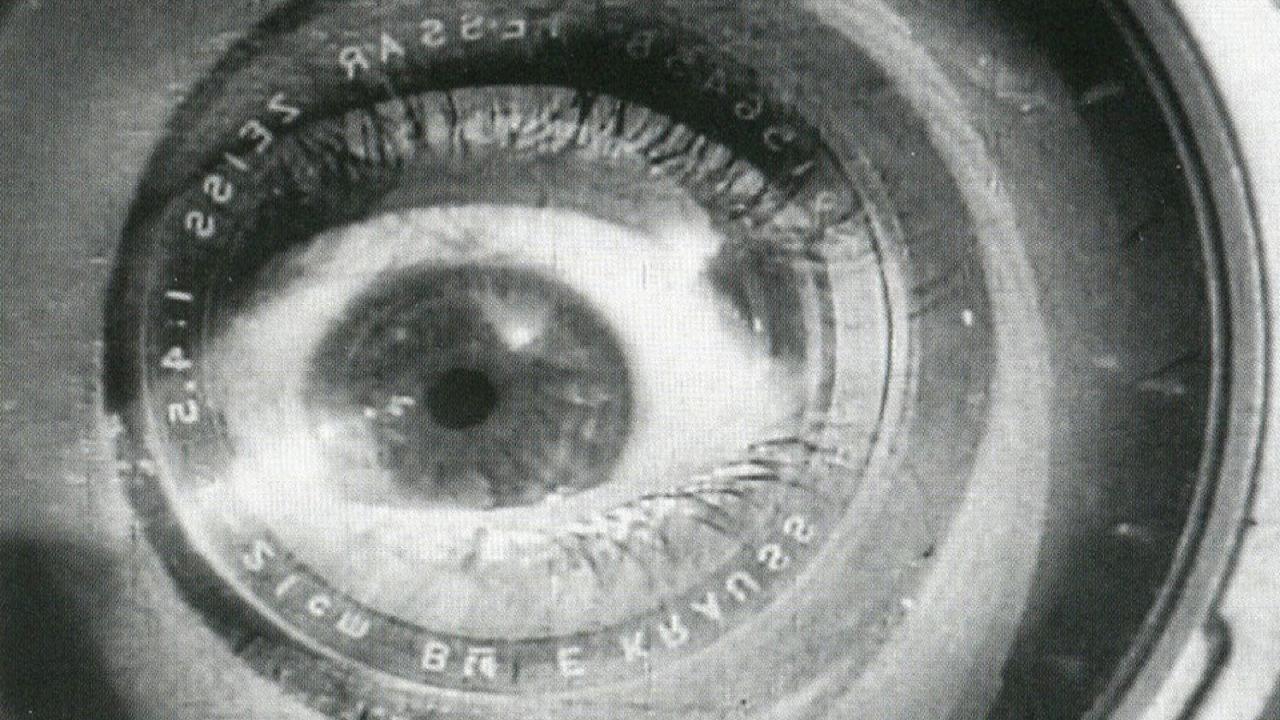

They challenged the attempt from capitalist cinema in Europa and America to restrict the new medium to the narrative traditions imported from the bourgeois novel and theatre. Hence, Vertov’s manifesto at the beginning of Man with a Movie Camera to “present an experiment in cinematic communication” that would have no intertitles, no scenario, no sets or actors, thereby “creating a truly international absolute language” separate from literature and theatre. During the film he plays with the audience expectations of narrative structures and conventions only to reject them.

His vision for a new cinema was one that strived to capture life “as it is”, unaware of being observed, and at the same time one that presented images that only a camera and not the eye could. Needless to say, these two objects sometimes clashed as we see scenes that are obviously staged for the camera. Ultimately, though, they were subordinated Vertov’s aim to make his viewer evolve ”from a bumbling citizen through the poetry of the machine to the perfect electric man”. A new man for a new society, no less!

The new waves of the 1960s cinema would connect with his ideas, although coming nowhere near his radical experiments. His practice of film was musical, having been trained as one in his early years, and the furious energy by which he mixes his symphony of split-screen imagery, dissolves, flickering frames, slow motion photo, pans, swish pans, animation, extreme angles, freeze frames, hand-held camera shots, super-imposition and a whole range of other camera and editing tricks has never been matched by anyone so far.

The two editions of the film – the UK one having a better translation of the title – present new digital transfers with cleaned-up images in full frame. It looks outstanding when shown on a home cinema projector on a big screen – the next best thing to having been at the 1929 premiere in Moscow. The American release presents the main attraction with a soundtrack by the Alloy Orchestra following the direction of Vertov’s notes for the film music (it is also available in the YouTube presentation of the film). Furthermore, it restores the original music the other films. The BFI decided to let Michael Nyman’s new score accompany Man with a Movie Camera, and electronic experimentalist group Mordant Music made the soundtrack to the two other films.

In a perfect world we would have an edition that included all the features of both the US and the UK editions, and choosing between the two is hard. But although purists will miss the original music score, the UK edition has subtitles that explain many of the signs and posters that swish by the camera and it features excellent comments by professor Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago. He guides the viewer – veteran scholars and fresh new cineastes alike – through the film with entertaining expertise.

© Michael Tapper, 2015. Web exclusive: michaeltapper.se 2015-11-12.

Further reading:

DZIGA VERTOV, a portrait of the director in Australian online journal Senses of Cinema.

Vlada Petric (1987), Constructivism in Film: The Man with a Movie Camera, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Yuri Tsivian (ed. 2004), Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, Pordenone: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto.

Dziga Vertov (1995) ‘On Kinopravda (1924) and The Man with the Movie Camera (1928)’ in Annette Michelson (ed.) Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, Los Angeles: University of California Press.