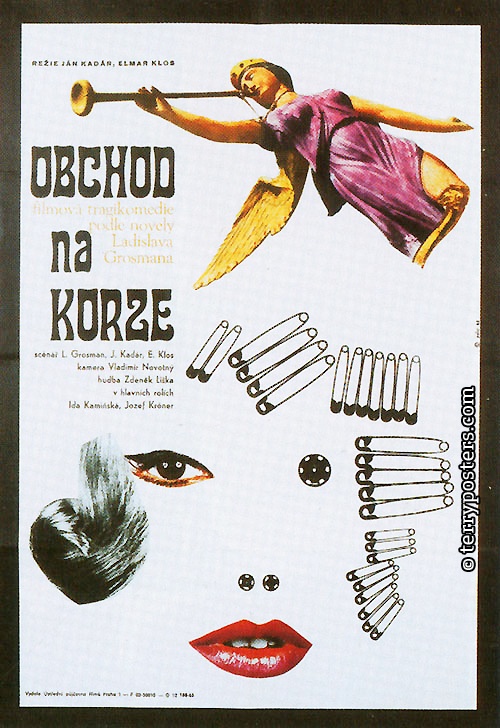

Obchod na korze

Obchod na korze

Czechoslovakia 1965

Bluray from Second Run, United Kingdom (region free). A new HD transfer from the Czech National Archive. Special features: A filmed film appreciation by writer Michael Brooke. Essay by author Peter Hames. US press book

Ján Kadár’s (1918–79) and Elmar Klos’ (1910–93) The Shop on the High Street was Czechoslovakia’s first film to receive an Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. However, it was almost immediately overshadowed by the youthful new wave of filmmakers, headed by Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, Věra Chytilová and Jiří Menzel, who would recieve an Academy Award in 1967 for Closely Watched Trains (Ostre sledované vlaky, 1966). Ironically, this generation got their training at the film school FAMU under Kadár.

Director duo Kadár & Klos were of an older generation, one who bore the stamp of the interwar and World War II years of fighting fascism. They began working together in 1952 on the film Kidnapped (Unos), and as members of the Communist Party they were largely protected from censorship and attacks in the press. But that would soon change, starting in 1955 with the ban on their musical comedy Music from Mars (Hudba z Marsu), a satire on bureaucratization released only after President Zápotocký’s personal intervention.

Even more severe was the clampdown on their 1958 film Three Wishes (Tří přaní, 1958), a film exposing a social climate of corruption and hypocrisy in the Communist state. Both the film and the filmmakers were slammed with a five-year ban. They got their revenge with the 1963 comeback film, World War II drama Death Is Called Engelchen (Smrt si říká Engelchen). It became a surprise hit and reaped the Golden Prize at the Moscow Film festival.

The success made it possible for them to make The Shop on the High Street, based on Slovak-Jewish author Ladislav Grosman’s (1921–81) screenplay, which in turn was an elaboration on his short story “The Trap” (“Past”). His story is set in a 1942 small-town in Slovakia, a country ruled by a Nazi Germany marionette regime that copied just about everything from their marionettist, down to the uniforms and the anti-Semitic laws. A local potentate in the SS-lookalike Hlinka Guard decides that to do his brother-in-law, the poor carpenter Anton ”Tóno” Brtko, a favor by letting him be the “Aryan controller” over a small Jewish shop, essentially making him the shop’s legal owner. The catch is that it is a small haberdashery and it barely makes a dime.

Moreover, it is owned by the old widow Rozália Lautmannová, who is virtually deaf and completely disconnected from what is going on in the world. Consequently, she misunderstands just about everything Tóno says and what happens outside the shop. To her, Tóno is just an assistant helping her in the shop, and when not serving the few customers that remain, she retreats back to her apartment and the memories of her dead husband. In order to keep up the appearances and make Tonó look like he is the shopkeeper living off the profits, the local Jewish community therefore decide to collectively pay him weekly.

Soon the relations grow warm between the peevish carpenter and the confused widow, and they enjoy what one could call a mutual understanding of monologues. A running joke is that she mishears his name Brtko as “Krtko”, which means “the mole”, and at the start he also is, although for the fascist government. At the end he is one for the opposition, and even if his last act seems like one out of defeatism, it could also be interpreted as the last resort of resistance.

To Kadár, who was Slovak-Jewish and had lost his parents and sister in the Holocaust, the film was of particular significance. He and Klos decided to shoot it on location in Sabinov, Slovakia, and with mostly local actors in the cast. In the leading part of the carpenter Brtko they chose the author and amateur actor Josef Kroner (1924–98), who was a familiar name in Czechoslovak films and also in Bulgaria and Hungary. Ida Kamińska (1899–1980) was chosen for the part of the Jewish widow. She was a key figure and star in the Warsaw Yiddish theater since the 1920s, and she got an Oscar nomination for the role.

The Shop on the High Street is a good example of Kadar & Klos’ style, adding absurdist and surrealist features to the main style of social realism, for instance in the celebration of the fascist monument erected on the square outside the shop and in the dream at the end of the film that counters the black finale with a parodic Hollywood happy end. Their brand of satire, of course, goes back to the tradition from Jaroslav Hašeks classic novel The Good Soldier Švejk (Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, 1923). In turn, their legacy of style and humor is instantly recognizable in the Czechoslovak new wave films of Chytilová’s Daisies (Sedmikrásky, 1966) and Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball (Hoří má panenko, 1967).

In this film, satire is also instrumental in the portrayal of the absurdities that follows when fascism comes to town – the disruption of the community and the opportunism of greed. There are however also surprising instances of silent resistance, such as Brtko’s friend Kuchar’s open defiance, Brtko’s own efforts to keep Rozália out of harm’s way and the neighbor who quietly shelters a Jewish kid when the transports to the concentration camps finally arrive.

After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the film was banned. Kadár & Klos still managed to complete one more feature, the poetic Adrift (Touha zvaná Anada, 1969, released in 1971), before Kadár emigrated to the US. Ida Kaminská soon followed. She made her American debut in 1969 in Kadár‘s surreal film The Angel Levine, which was summarily dismissed by the critics and quickly forgotten. Kadár drifted into television, making his last stand before his death in 1979 with Freedom Road, originally a four-hour miniseries that is now only available only in a 95 minute edition about the first African American senator in US history: Gideon Jackson, played by Muhammad Ali.

Klos stayed at home and was for 20 years dismissed both from the film studios and from the film school FAMU. When returning to film school he completed one more film, Bizon (1989), together with one of his pupils, Moris Issa. Screenwriter Ladislav Grosman also fled Czechoslovakia at the invasion. He settled in Tel Aviv, eventually becoming the Professor of Slavic literature at the Bar-Ilan University.

The Shop at the High Street marks the artistic height for all of the talents involved. It has for long been out of the limelight, due to the new wave, the 1968 Soviet invasion and the following 20 years of repression. This bluray release has followed a period of reappreciation of Kadár & Klos‘ works in their respective home countries of Slovakia and the Czech Republic with books, exhibitions and retrospectives.

© Michael Tapper 2016. Web exclusive: michaeltapper.se 2016-10-21.